Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000874

Accepted 26 January 2026 - Published online

7 February 2026

Relationship Between Left Ventricular Remodeling Assessed by Strain Echocardiography and Conventional Echocardiography Before and After Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy in Severe Heart Failure Patients

bHospital of Vietnam National University, Vietnam National University (Hanoi), Vietnam

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

To assess the relationship between left ventricular remodeling as evaluated by strain echocardiography and conventional echocardiography before and after cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in patients with severe heart failure patients.Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study with follow-up comparison before and after. The study was conducted on 33 heart failure patients indicated for CRT at the Vietnam National Heart Institute, Bach Mai Hospital from late 2015 to December 2021.Results:

The study showed some correlations and changes in left ventricular remodeling assessed by strain echocardiography and conventional echocardiography before and after CRT. Left ventricular end-systolic volume and end-diastolic volume significantly decreased after 3 months of follow-up (p < 0.001) and had a strong inverse correlation with QRS recovery in study patients (r = 0.65). A positive correlation was observed between changes in left atrial volume index (LAVI) and 4B strain (r = 0.96, p < 0.05). After 3 months of CRT implantation, there was a positive correlation between the isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) and left atrial volume (LAVI) (p < 0.05) and between the left atrial volume and E/e' obtained from tissue Doppler (r = 0.53, p < 0.05). However, there was no correlation observed between E/e' and total EF (r = -0.36, p > 0.05), between 2B strain and total EF (r = -0.36, p > 0.05) and between 2B strain and left atrial volume LAVI (r = 0.36, p > 0.05).Conclusion:

Strain echocardiography is an important tool that cannot be overlooked in diagnosing, assessing risk factors, and monitoring heart failure. After 3 months of CRT implantation, there was significant improvement in left ventricular volume and ejection fraction (EF). This indicates better treatment effectiveness.Introduction

Globally, the prevalence of heart failure is 1-2% [1], and it is most common in the elderly. In Vietnam, the incidence of heart failure is also high [2], and following global trends, Vietnam is also performing Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) for patients with severe heart failure who meet the indications [3].

The emergence and development of CRT since the 1990s have opened a new direction in heart failure treatment and have raised many new issues related to the pathogenesis of heart failure, especially in the context of cardiac remodeling and myocardial dyssynchrony (MDB) [3].

Echocardiography helps assess ejection fraction (EF), and is an important tool for evaluating cardiac function, identifying structural abnormalities, helping to determine the cause of heart failure or other risk factors, helping to monitor early treatment, assessing heart function improvement and related factors. As people age, natural aging processes can cause changes in heart structure such as thickening heart walls, enlarged chambers, and reduced contractility. Simultaneously, an aging population also faces an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases like coronary artery disease, hypertension, and valvular heart disease. However, studies on the relationship and changes in left ventricular function have been conducted worldwide, but an in-depth assessment of heart failure patients indicated for CRT has not been extensively investigated. Therefore, we conducted this study to understand the relationship between left ventricular remodeling assessed by strain echocardiography before and after cardiac resynchronization therapy compared to conventional echocardiography in heart failure patients indicated for CRT.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

The study was conducted as a cross-sectional descriptive study with follow-up comparison before and after.

Study Subjects: The study subjects included patients with severe heart failure, with an EF <

35%, who

were undergoing optimal medical treatment for heart failure in NYHA III - IV, and who were indicated for

cardiac

resynchronization therapy based on echocardiographic results, electrocardiogram, biochemical results, and

clinical symptoms when implanted with cardiac resynchronization devices at Bach Mai Hospital Heart

Institute.

Patients receiving cardiac resynchronization devices were selected based on ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines [4].

Time and location research

The study was conducted at the Vietnam National Heart Institute, Bach Mai Hospital, from late 2015 to

December

2021.

Sampling Method

Convenience sampling. A total of 33 patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in

the

study were selected. These were all patients who met the criteria and followed all steps in the research

process.

Research Progress

Clinical Examination: All patients underwent a general examination to assess heart failure status

NYHA

III – IV (NYHA Class I: Cardiac disease, but no symptoms and no limitaion in ordinary physical activity;

NYHA

Class II: Mild symptoms and slight limitations during ordinary activity; NYHA Class III: Significant

limitations

in activity due to symptoms, comfortalbe only at rest.; NYHA Class IV: Servere limitations, symptoms even

while

at rest).

The follow-up period after implantation was 6 months. Patients were treated according to ACC/AHA 2008

guidelines

for at least 6 months. [4]. Patients received priority treatment for various types of medications such as

ACE

inhibitors, ARBs, Beta-blockers, and Digoxin.

Biochemical Tests

Some main biochemical parameters were collected, including: Pro BNP, Urea, Creatinine, SGOT, SGPT.

Imaging: Doppler ultrasound, tissue Doppler ultrasound. The classify heart failure (HF) based on

Left

ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF): HF with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HfrEF) is EF ≤ 40%; HF with Midly

Reduced Ejection Fraction (HfmrEF) 41-49%; FF with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HfpEF) ≤ 50%.

Research procedure (Research diagram)

Select patients with severe heart failure (NYHA III – IV), EF < 35%, after optimal medical treatment,

sinus

rhythm was restored. Perform Doppler echocardiography beforehand. Patients with indications for pacemaker

implantation will have a CRT implanted. Each patient will undergo echocardiography 4 times: Before

pacemaker

implantation, immediately after pacemaker implantation, after 1 month, and after 3 months.

Cardiac Doppler Ultrasound Method

The Cardiac Doppler ultrasound was performed on all selected patients participating in the study using a

JIS6 ultrasound machine at the cardiac ultrasound room of the Vietnam National Heart Institute. The

measured results were assessed by a group including cardiac ultrasound specialists at the cardiac

ultrasound

department of the Vietnam National Heart Institute. Ultrasound parameters were measured and

calculated

according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography (2008) on an ultrasound machine

with

Tissue Doppler and myocardial tissue tagging functions, using the JIS6 ultrasound

machine.4

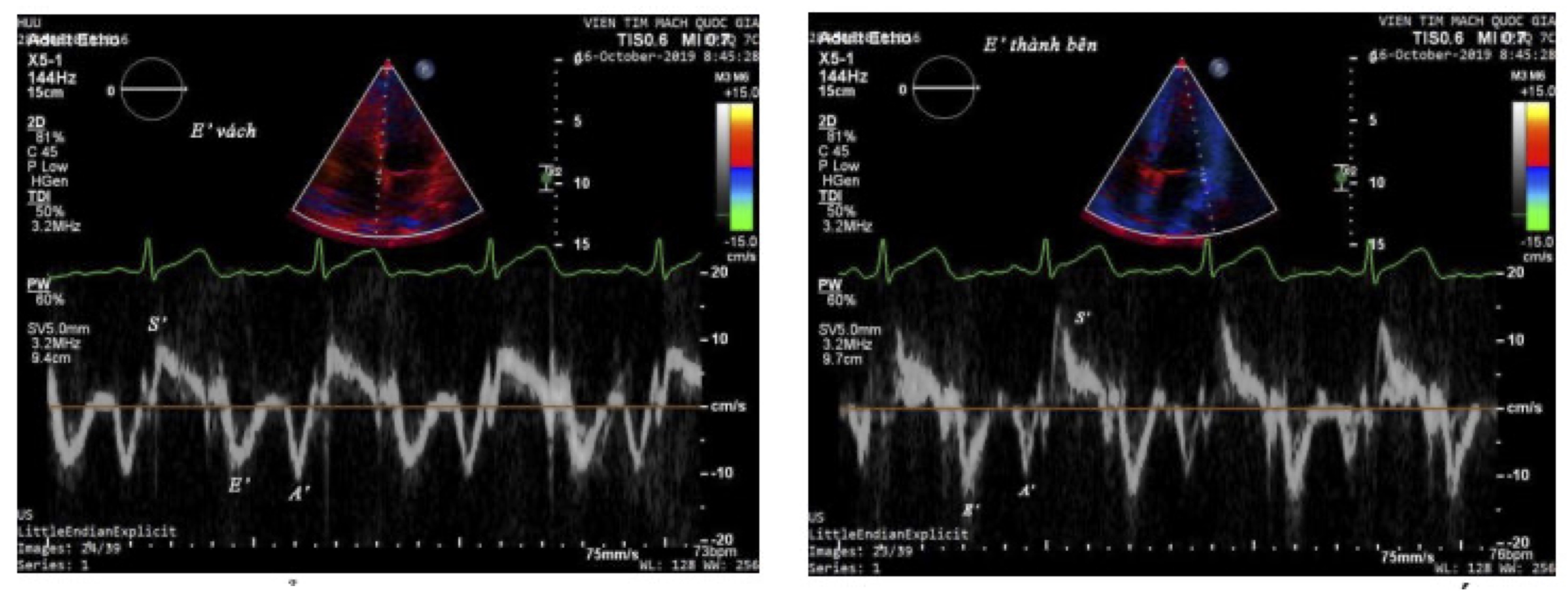

The ultrasound parameters were examined in the following sequence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Doppler ultrasound image of myocardial tissue

M-Mode Echocardiography

Measured from the parasternal long axis view, the following parameters were measured: Dd: left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter; Ds: left ventricular end-systolic diameter; %D: fractional shortening; Vd: left

ventricular end-diastolic volume; Vs: left ventricular end-systolic volume; Aortic diameter, left atrial

diameter, and right ventricular long-axis diameter; EF (Teichholz): left ventricular ejection fraction.

2D Echocardiography

Measured from the apical four-chamber and two-chamber views. Left ventricular volume and ejection fraction

were

calculated using the Biplane Simpson's method (four-chamber and two-chamber views). Left ventricular

end-systolic volume and end-diastolic volume were measured. The parameters for left ventricular

end-diastolic volume (Vd) and end-systolic volume (Vs) were averaged from the two views (Biplane). The

average

left atrial volume index (LAVi) was calculated from both the apical four-chamber and two-chamber views.

Pulsed Wave Doppler Echocardiography

Measured from the apical four-chamber and five-chamber views. In the apical four-chamber view, the Pulsed

Wave

Doppler sample volume was placed at the free edge of the anterior mitral leaflet, measuring the maximum

velocity

of E wave, A wave, and E wave deceleration time (DT). In the apical five-chamber view, the Pulsed Wave

Doppler

sample volume was placed between the left ventricular outflow tract and the free edge of the anterior

mitral

leaflet, measuring the isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT).

Continuous Wave and Color Doppler Echocardiography

Measured from the apical four-chamber and two-chamber views.

Tissue Doppler Echocardiography

Measured from the apical four-chamber view with the Tissue software available on the ultrasound machine.

The

Doppler sample volume was placed at the basal interventricular septum using the TDI software, measuring

the

velocity of e', a', and s' waves. The Doppler sample volume was placed at the basal lateral wall of the

left

ventricle using the TDI software, measuring the velocity of e', a', and s' waves.

Speckle Tracking Echocardiography (Myocardial Tissue Tagging)

Measured from the apical long-axis, two-chamber, and four-chamber views, using the Speck tracking software

to

measure online and calculate the myocardial strain parameter; This includes Longitudinal Strain,

Four-Chamber Strain, Two-Chamber Strain, and Global Longitudinal Strain (GLS) for all cardiac chambers.

Whether

strain analysis was performed by a team of echocardiography experts at the Vietnam National Heart

Institute, and

the final analysin result and agreed upon by the team and the expert leader.

Doppler Ultrasound to Evaluate Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) Response

Patients underwent Doppler echocardiography with all the same parameters as measured before CRT device

implantation. Each patient had echocardiography performed immediately after CRT implantation at 1

month,

and at 3 months post-implantation, and these parameters were monitored. The EF value presentation

was

clarified (Change in EF value relative to baseline).

Data Collection Method

All data was collected according to a pre-designed patient follow-up form. Collected data included

demographic

characteristics, clinical symptoms, and echocardiographic parameters of patients (echocardiography

collected

according to hospital results) upon admission and until the 3rd month after cardiac resynchronization

device

implantation.

Data processing and statistical analysis method

Data was processed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc South Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL) and Stata 12.0 to identify

significant values and find statistically significant parameters. The results were presented using tables

or

appropriate graphs; for continuous variables, results were presented as mean ± standard deviation, for

categorical variables, results were presented as percentages. T-test (for 2 variables), ANOVA test (for

more

than 2 variables) were used to compare continuous variables; Pearson correlation test was used to examine

the

relationship between categorical variables, Fisher's exact test was used for small sample size categorical

variables. Odds ratios (OR) were used to analyze factors influencing the results of pacemaker implantation

in a

2x2 table. Statistically significant differences were defined as p < 0.05 [5].

Research Ethics

The study was only conducted with the consent of participating patients. Patients participating in the

study

were treated according to the professional regulations of the Vietnam Ministry of Health, as well as those

of

the Vietnam National Heart Institute, Bach Mai Hospital. All patient information was kept absolutely

confidential, and the results were used solely for research purposes.

Results

General Characteristics of the Study Population

The study included 33 patients with severe heart failure indicated for CRT. The mean age of the patients

was

57.8 years; patients aged ≥60 years accounted for 57.6% (n = 19), while patients <60 years accounted

for

42.4% (n = 14). The male-to-female ratio was 81.8% (n = 27) to 18.2% (n = 6).

Changes in Conventional Echocardiographic Parameters After CRT

After 3 months of CRT implantation, left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) and end-diastolic volume

(LVEDV) significantly decreased compared with baseline (both p < 0.001). Left ventricular ejection

fraction

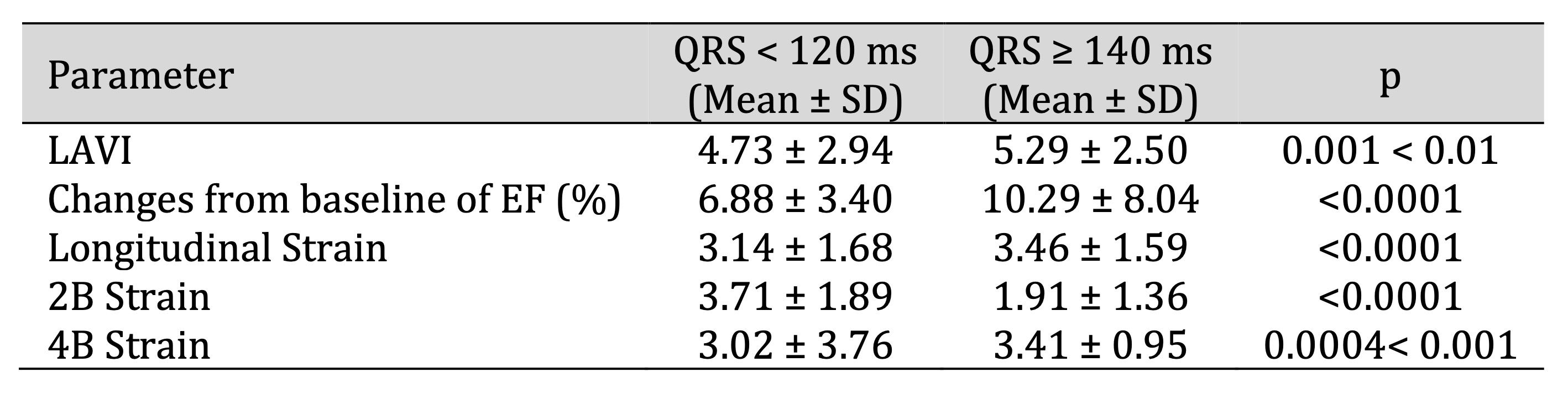

(EF) also showed a significant improvement after CRT implantation (Table 1).

Table 1: Relationship of Positive change in echocardiographic parameters according to QRS duration at baseline and after 3 months of CRT implantation. Comments: Left ventricular volume and EF significantly improved after CRT implantation after 3 months, with p < 0.001. There was a strong inverse correlation with QRS recovery on the electrocardiogram of patients in the study group, with a correlation coefficient of 0.65

Relationship Between QRS Duration and Left Ventricular Remodeling

After 3 months of CRT implantation, QRS duration significantly decreased compared with baseline (p <

0.001).

QRS recovery showed a strong inverse correlation with left ventricular volumes, with a correlation

coefficient

of r = 0.65 (Table 1).

Changes in EF differed according to QRS duration. In patients with QRS between 120 and 140 ms, the mean

change

in EF was 6.88 ± 3.40%, whereas in patients with QRS ≥140 ms, EF increased by 10.29 ± 8.04% (Table 1).

Significant changes in myocardial strain parameters were also observed according to QRS recovery after

CRT

implantation (Table 1).

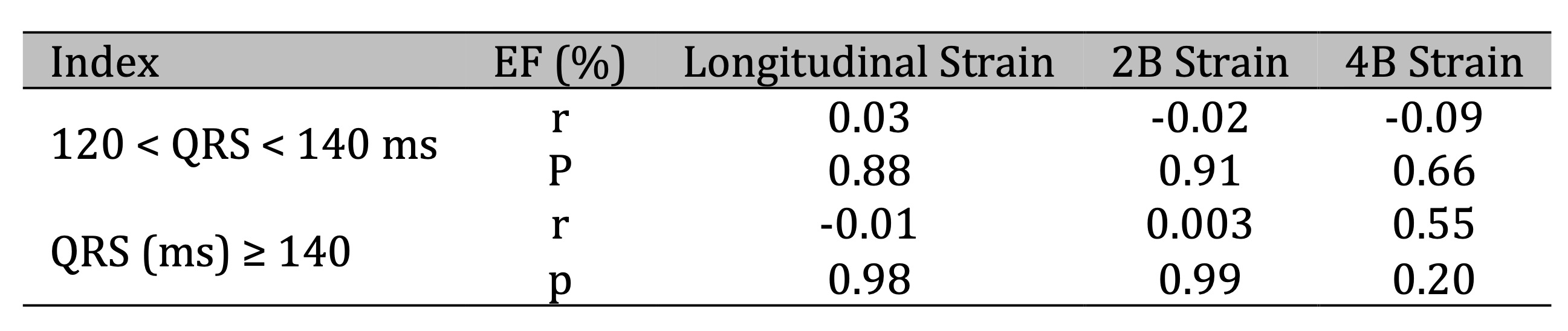

Relationship Between Left Atrial Volume and Myocardial Strain

A significant positive correlation was observed between changes in left atrial volume index (LAVI) and

four-chamber (4B) myocardial strain in patients with QRS ≥140 ms (r = 0.96, p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2: Relationship between positive changes in left atrial volume (LAVI) and myocardial strain according to QRS duration before and after CRT implantation. Comments: There was a significant positive correlation between the positive change in left atrial volume (LAVI) and myocardial 4B strain in the QRS (ms) ≥ 140 group (r = 0.96, p < 0.05)

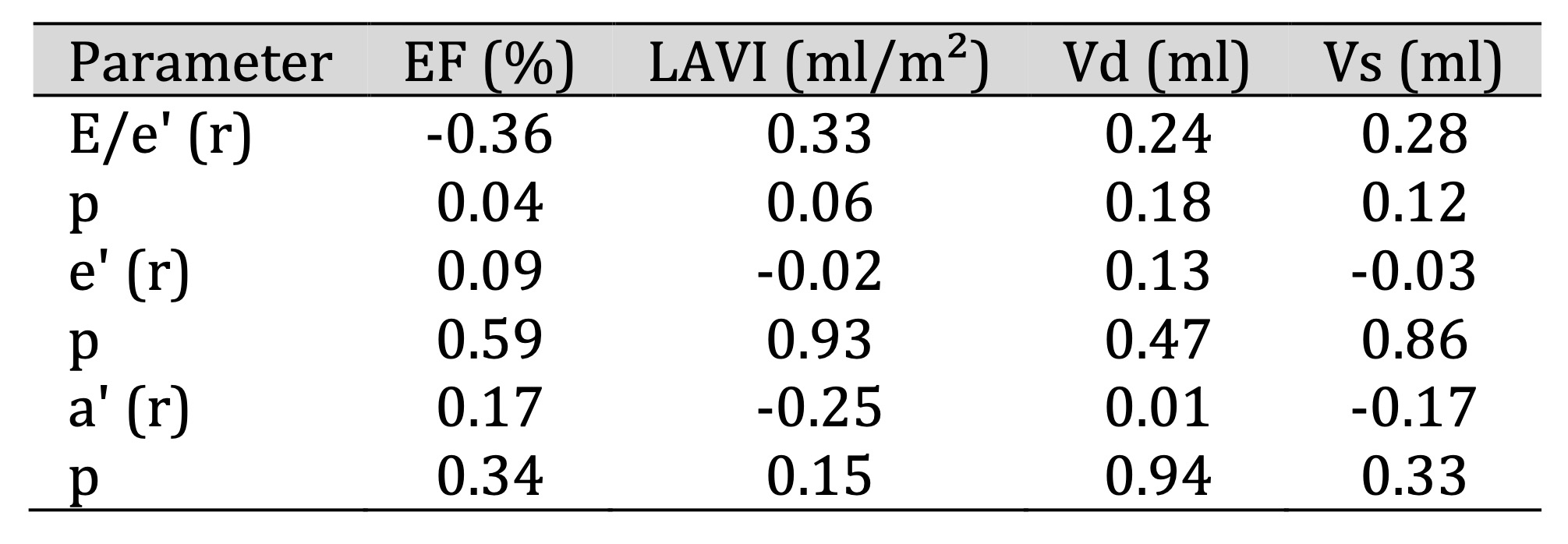

Diastolic Function Parameters After CRT

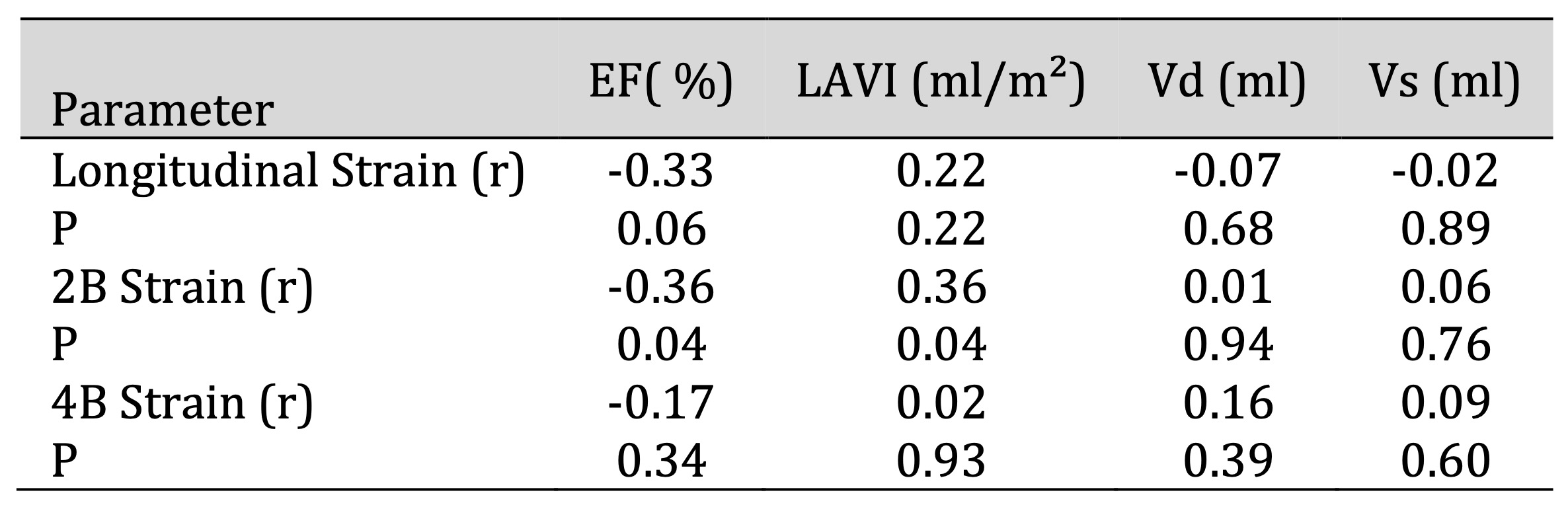

At 3 months after CRT implantation, a significant inverse correlation was observed between E/e′ ratio

and

total

EF (r = −0.36, p < 0.05) (Table 3). A significant inverse correlation was also found between

two-chamber (2B)

strain and EF (r = −0.36, p < 0.05), as well as a positive correlation between 2B strain and left

atrial

volume (r = 0.36, p < 0.05) (Table 5).

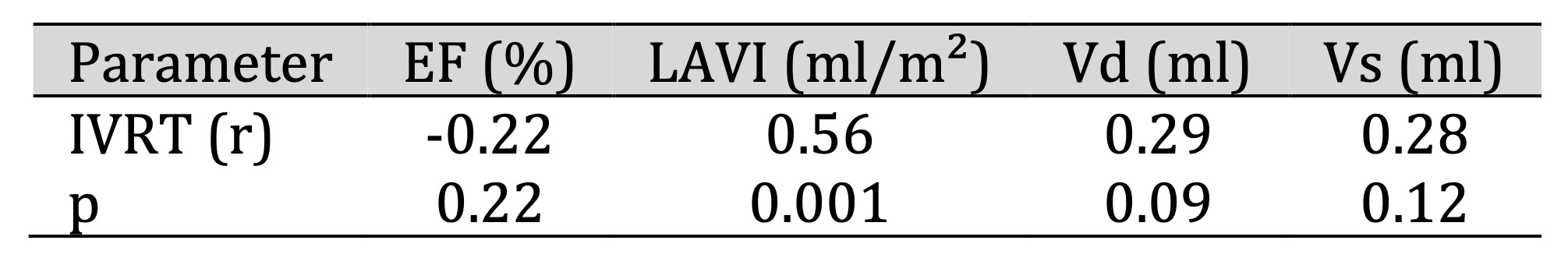

In addition, a significant positive correlation was observed between isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT)

and

LAVI

at 3 months after CRT implantation (r = 0.66, p = 0.001) (Table 4). A positive correlation was also

found

between LAVI and E/e′ measured by tissue Doppler (r = 0.53, p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3: Relationship between tissue Doppler echocardiographic parameters and total EF (%), LAVI, Vd, Vs at 3 months after CRT implantation. Comments: At 3 months after implantation: There was a significant inverse correlation between E/e’ ratio and total EF (r = -0.36, p < 0.05)

Table 4: Relationship between echocardiographic parameters and isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) at 3 months after implantation. Comments: At 3 months after implantation: There was a significant positive correlation between IVRT and left atrial volume index (LAVI) (p < 0.05)

Table 5: Relationship between 2D echocardiographic parameters and myocardial strain at 3 months after implantation. Comments: At 3 months after implantation, there was a significant inverse correlation between 2B strain and total EF (r = -0.36, p < 0.05) and a significant positive correlation with left atrial volume LAV (r=0.36, p < 0.05)

Discussion

Demographic Characteristics

The mean age of patients in this study was 57.8 years, with a higher proportion of patients aged

≥60

years. This

age distribution is consistent with the epidemiology of severe heart failure and reflects the

typical

population

indicated for CRT [1,2].

QRS Duration and Left Ventricular Remodeling

The present study demonstrated a significant association between QRS duration and left

ventricular

remodeling.

QRS narrowing after CRT implantation was associated with reductions in left ventricular volumes

and

improvement

in EF, supporting the concept that electrical resynchronization contributes to reverse

remodeling. These

findings are consistent with previous studies reporting improved ventricular function in

patients with QRS

narrowing after CRT implantation [6–10].

Role of Strain Echocardiography in CRT Assessment

Strain echocardiography provides a sensitive assessment of myocardial deformation and allows

detection of

subtle

functional changes that may not be apparent with conventional echocardiography. The observed

associations

between myocardial strain parameters and QRS recovery highlight the value of strain imaging in

evaluating

CRT

response, particularly in patients with wider QRS complexes [13].

Left Atrial Volume and CRT Response

Left atrial volume index reflects chronic diastolic burden and elevated filling pressures. The

observed

relationship between changes in LAVI and myocardial strain suggests that atrial remodeling

parallels

ventricular

functional improvement following CRT implantation. This finding is in line with previous studies

indicating that

LAVI may serve as a predictor of CRT response [14,19].

Diastolic Function Parameters

The observed relationships between E/e′ ratio, EF, IVRT, and LAVI indicate that diastolic

function

improves

alongside systolic function after CRT implantation. Increased E/e′ ratio and prolonged IVRT were

associated with

impaired ventricular performance, supporting the role of tissue Doppler echocardiography in

monitoring

diastolic

function in heart failure patients undergoing CRT [15–20].

Clinical Implications

Overall, these findings emphasize the complementary role of strain echocardiography and

conventional

echocardiography in assessing left ventricular remodeling and treatment response after CRT.

Echocardiography

remains an indispensable tool for diagnosis, risk stratification, and follow-up in patients with

severe

heart

failure.

Conclusion

This study revealed several relationships between left ventricular remodeling assessed by strain echocardiography and conventional echocardiography before and after CRT in severe heart failure patiens: Left ventricular volume before and after CRT implantation showed significant changes from 1 to 3 months (p < 0.001) and had a strong positive correlation with the QRS complex on the electrocardiogram of patients in the study group (r = 0.65). There was a significant positive correlation between the change in left atrial volume (LAVI) and myocardial 4B strain in the QRS (ms) ≥ 140 group (r = 0.96; p < 0.05). At 3 months after CRT implantation, there was a significant positive correlation between isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) and left atrial volume (LAVI) (p < 0.05), and between left atrial volume and E/e' parameter measured by tissue Doppler (r = 0.53; p < 0.05). However, there was an inverse correlation between E/e' ratio and total EF (r = -0.36; p < 0.05), between 2B strain and total EF (r = -0.36; p < 0.05), and between 2B strain and left atrial volume LAV (r = 0.36; p < 0.05).

Thus, echocardiography, especially tissue Doppler echocardiography, is an indispensable tool in diagnosing, assessing risk factors, and monitoring heart failure. At 3 months after CRT implantation, there was a significant improvement in left atrial volume and ejection fraction (EF), with statistically significant results indicating better treatment effectiveness after 3 months of CRT implantation.

Limitations And Recommendations

This study still has some limitations that need to be addressed in subsequent, larger-scale

studies on

this

issue: The smal sample size and sample size was not large enough (we recruited 33 patients), but

each

patient

directly underwent echocardiography at 4 time points (before implantation, immediately after

implantation,

1

month after implantation, and 3 months after implantation); The study was conducted at a single

center

(Single-center study); A comparative study with a control group was not performed (Lack of a

control

group); And

the follow-up time was not long enough (Short follow-up period). Therefore, we recommend that

new studies

are

needed on the role of echocardiography in evaluating the effectiveness of heart failure

treatment after

CRT

implantation, with a larger sample size, and potentially conducted as a multi-center study on

this issue.

Abbreviations

CRT ((Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy) - Cardiac resynchronization therapy; Dd (End diastolic diameter) - End-diastolic diameter; Ds (End systolic diameter) - End-systolic diameter; Ao (Aorta) – Aorta; EF (Ejection fraction) - Ejection fraction; NYHA (New York Heart Association) - New York Heart Association classification; Vd (End diastolic volume) - End-diastolic volume; Vs (End systolic volume) - End-systolic volume; VLT (Left Ventricle) - Left Ventricle; LA (Left Atrium) - Left Atrium; LAVi (Left atrium Interventricular) - Left atrial volume index; E/A (Early diastolic filling/Atrial contraction) - Ratio of early diastolic flow velocity and atrial contraction velocity in mitral inflow (E wave and A wave); E/e' - Ratio of early diastolic mitral inflow velocity to early diastolic myocardial velocity at the mitral annulus; e' (tissue Doppler velocity) - Early diastolic myocardial velocity; IVRT (Isovolumic Relaxation Time) - Isovolumic relaxation time; s' (s-prime) - Peak systolic myocardial velocity; a' (a-prime) - Peak late diastolic myocardial velocity; VTI (Velocity Time Integral) - Velocity Time Integral; TAPSE (Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion) - Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE); IVS - Interventricular septum; GLS (Global Longitudinal Strain) – Global Longitudinal Strain.);

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

| 1 | McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, etal., ESC committee for practice Guidelines. ESC

guideline

for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task force

for the

Diagnosis and treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart failure 2012 of the Eropean Society of

Cardiology. Developedi n collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) ofthe ESC.

Eur Heart

J. 2012; 33:1787-1847.

|

| 2 | Chu SD, Doan QH, Tran MT, et al. Individualized treatment strategy for acute

exacerbation of

chronic heart failure in patient with dilated cardiomyopathy: What is the optimal

treatment? Pak

Heart J 2024; 57 (01): 192-198.

|

| 3 | Dought RN, Whalley GA, Walsh HA et al. Effect of carvedilolon out come aftermyocardial

in farction

in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomisedtrial. Lancet 2001;

357:

1385-1390.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04560-8 |

| 4 | Epstien EA, DiMarco JP, etal., ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for Device-Based therapy of

cardiac

Rhythm Abnormallities; JACC. 2008; 21: 1-62.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.032 |

| 5 | Saunders BD,Trapp RG., Basic& CliniccalBiostatisstics 2n. Prentice - HallInternational

Inc. 1994.

|

| 6 | Rickard J, Popovic Z, Verhaert D, Sraow D, Baranowski B, Martin DO, Lindsay BD, Varma N,

Tchou P,

Grimm RA, Wilkoff BL, Chung MK. The QRS narrowing index predicts reverse left ventricular

remodeling

following cardiac resynchronization therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011

May;34(5):604-11. doi:

10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.03022.x. Epub 2011 Jan 28

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.03022.x |

| 7 | De Winter O, Van de Veire N, Van Heuverswijn F, Van Pottelberge G, Gillebert TC, De

Sutter J.

Relationship between QRS duration, left ventricular volumes and prevalence of nonviability

in

patients with coronary artery disease and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Heart

Fail.

2006 May;8(3):275-7 doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.001. Epub 2005 Nov 21

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.001 |

| 8 | Guo Z, Liu X, Cheng X, Liu C, Li P, He Y, Rao R, Li C, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Luo X, Wang J.

Combination

of Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Diameter and QRS Duration Strongly Predicts Good

Response to and

Prognosis of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Cardiol Res Pract. 2020 Jan

17;2020:1257578. doi:

10.1155/2020/1257578.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1257578 |

| 9 | Rickard J, Baranowski B, Grimm RA, Niebauer M, Varma N, Tang WHW, Wilkoff BL. Left

Ventricular

Size does not Modify the Effect of QRS Duration in Predicting Response to Cardiac

Resynchronization

Therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2017 May;40(5):482-487. doi: 10.1111/pace.13043.

https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.13043 |

| 10 | Rickard J, Popovic Z, Verhaert D, Sraow D, Baranowski B, Martin DO, Lindsay BD, Varma N,

Tchou P,

Grimm RA, Wilkoff BL, Chung MK. The QRS narrowing index predicts reverse left ventricular

remodeling

following cardiac resynchronization therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011

May;34(5):604-11. doi:

10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.03022.x. Epub 2011 Jan 28.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.03022.x |

| 11 |

https://www.itmedicalteam.pl/articles/impact-of-cardiac-resynchronizationtherapy-on-heart-failure-patientsexperience-from-one-center-103959.html

|

| 12 | De Winter O, Van de Veire N, Van Heuverswijn F, Van Pottelberge G, Gillebert TC, De

Sutter J.

Relationship between QRS duration, left ventricular volumes and prevalence of nonviability

in

patients with coronary artery disease and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Heart

Fail.

2006 May;8(3):275-7.doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.001.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.001 |

| 13 | Bax JJ, Delgado V, Sogaard P, Singh JP, Abraham WT, Borer JS, Dickstein K, Gras D,

Brugada J,

Robertson M, Ford I, Krum H, Holzmeister J, Ruschitzka F, Gorcsan J. Prognostic

implications of left

ventricular global longitudinal strain in heart failure patients with narrow QRS complex

treated

with cardiac resynchronization therapy: a subanalysis of the randomized EchoCRT trial. Eur

Heart J.

2017 Mar 7;38(10):720-726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw506.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw506 |

| 14 | https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(16)44197-8/fulltext

|

| 15 | Kawaguchi M, Hay I, Fetics B, Kass DA. Combined ventricular systolic and arterial

stiffening in

patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: implications for systolic and

diastolic

reserve limitations. Circulation. 2003 Jul 8;107(26):351-7.doi:

10.1161/01.CIR.0000065421.30461.8B.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000048123.22359.A0 |

| 16 | Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, López B, Jin Y, Richart T, Thijs L, González A, Herregods MC,

Fagard RH,

Diez J, Staessen JA. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in a general

population.

Circ Heart Fail. 2009 Jan;2(1):105-12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.822011 Epub 2008

Nov 25.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.822627 |

| 17 | Sengupta PP, Krishnamoorthy VK, Korinek J, Narula J, Vannan MA, Lester SJ, Tajik JA,

Seward JB,

Khandheria BK, Belohlavek M. Left ventricular form and function revisited: applied

translational

science to cardiovascular ultrasound imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007

Nov;20(11):539-51. doi:

10.1016/j.echo.2007.02.014.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2007.02.014 |

| 18 | Reant P, Labrousse L, Lafitte S, Bordachar P, Pillois X, Tariosse L, Bonoron-Adele S,

Padois P,

Deville C, Roudaut R, Dos Santos P. Experimental validation of circumferential,

longitudinal, and

radial 2-dimensional strain during dobutamine stress echocardiography in ischemic

conditions. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jan 1;51(1):149-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.055.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.055 |

| 19 | Møller JE, Hillis GS, Oh JK, Reeder GS, Gersh BJ, Pellikka PA. Left atrial volume: a

powerful

predictor of survival after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003 Aug

5;107(30):2207-12.

doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066314.99751.68.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000066318.21784.43 |

| 20 | Wong TC, Piehler KM, Kang IA, Kadakkal A, Kellman P, Schwartzman DS, Mulukutla SR, Simon

MA,

Shroff SG, Kuller LH, Schelbert EB. Myocardial extracellular volume fraction quantified by

cardiovascular magnetic resonance is increased in diabetes and associated with mortality

and

incident heart failure admission. Eur Heart J. 2014 Dec 21;35(10):657-64.doi:

10.1093/eurheartj/eht174.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht174 |