Advances in the Study of Bronchial and Vascular Architecture of Lungs in the Rat’s Model: from Morphogenesis to Disease Modelling

bDepartment of Pharmacognosy of Azerbaijan Medical University, Baku, Azerbaijan,

cDepartment of Human Anatomy and Medical Terminology of Azerbaijan Medical University, Baku, Azerbaijan

Keywords

Abstract

Bronchial and vascular architecture in the rat lung forms an interdependent scaffold that balances ventilation with perfusion and adapts to metabolic demand. Development proceeds through coordinated branching programs that couple epithelial growth with vascular patterning while matrix remodeling and epithelial–mesenchymal crosstalk shape airway caliber and capillary alignment. Quantification has moved from classical design-based stereology to organ-scale µCT, optical clearing, and multiscale computational reconstructions that link structure to function. Across disease models, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and emphysema show distal airspace enlargement with vascular rarefaction, pulmonary hypertension (PH) features medial thickening and arteriolar muscularization, asthma combines epithelial remodeling with angiogenesis, and fibrosis exhibits collagen deposition with capillary regression. Convergent signaling networks integrate these changes, including VEGF and HIF pathways that govern angiogenesis, Notch and Wnt programs that regulate morphogenesis, and oxidative stress with cytokine and microRNA axes that drive vascular remodeling. Translational alignment is strengthened by single-cell and imaging biomarkers that map rat phenotypes to human pathology, while bioengineered platforms and in silico models provide controllable test beds for hypothesis testing. Predictive frameworks for remodeling across development and disease could be provided by standardized pipelines that combine morphometry, mechanics, and molecular profiles.

Introduction

The bronchial and vascular system of the lung ensures even ventilation and perfusion of the parenchyma [1]. Blood oxygenation occurs in the alveolar-capillary interface pulmonary vascular network, and the airflow is controlled by the bronchial tree [2]. Their interdependence in structure promotes effective gas exchange and adaptation to metabolic needs. The close spatial relationship between airway, vascular, lymphatic, and neural networks has also been demonstrated using high-resolution 3D imaging, highlighting the role of architectural integrity in promoting physiological resilience [3]. The study of both development and disease in mammalian lungs is based upon an understanding of these coupled systems.

The FGF10 FGFR2b signaling pathway is required to form lung airways, which is coordinated by biochemical cues and epithelial dynamics to form the hierarchical branching geometry that characterizes lung geometry [4]. The development of the vascular system occurs concurrently via endothelial-mesenchymal signaling, which guarantees the alignment with the airway tree [5]. Mechanistic theories, such as curvature-feedback through ERK, explain how the length and orientation of branches are regulated to achieve morphogenetic homeostasis, with comparative studies revealing that morphogenetic programs are adjusted to functional demands in different organs [6, 7].

The rat has been found to be a useful intermediate model due to its lung size, vascular structure, and hemodynamic accessibility; it has benefits over mice and retains experimental viability [8]. Postnatal µCT imaging indicates persistent alveolar and acinar remodeling, which allows better evaluation of developmental changes [9]. Its clinical value is highlighted by structural changes in heart failure and pulmonary hypertension [10]. The visualization of airway and vascular architecture is now done at high resolution with advanced μCT protocols and CT-based mapping [11, 12].

The recent innovations in stereology have enhanced the measurement of the lung compartments and have made the heterogeneous lesions to be sampled with precision [13]. The ex vivo lung perfusion is relevant to increase the physiological significance of structural evaluation [14]. Whole lung visualization is now achieved at the micron level using the techniques of tissue-clearing and 3D microscopy [15], and high-resolution histological reconstructions that consider the information about gene expression and spatial organization provide new information about the biological process [16]. All these innovations have transformed structural mapping of the rat lung and made it more useful in developmental and disease modeling.

Even though there are significant improvements, there are still gaps in knowledge. The majority of developmental research is based on mice, and rat data are still scarce, even though they are more physiologically similar to humans [17]. The research on airway or vascular remodeling is frequently studied in isolation from each other as opposed to coordinated structural systems [18]. Perfusion pressures and contrast techniques influence distal vascular accuracy, whereas 3DCT and tissue clearing have enhanced visualization [19, 20]. The heterogeneous lesions might be undersampled during the stereological analyses, and thus there is a need to use adaptive sampling and standardised imaging protocols [19]. As a result, there is no single synthesis of morphogenesis, structural mapping, and disease remodeling of rat lungs.

The review is a synthesis of bronchial and vascular architecture of the rat lung with focus on developmental organization, structural interdependence, and pathological remodeling. It combines morphometric, computational, and advanced imaging methods, such as µCT, optical clearing, and corrosion casting, to address discrepancies and explain the shortcomings of methods. Consolidation of the structural baseline can increase the reproducibility, increase comparisons between developmental and disease states, and better translational modeling of airway-vascular coupling. The review offers a consistent framework to answer the major conceptual and methodological gaps in the existing rat lung studies by integrating insights on normal morphogenesis and disease-related remodeling.

The review was created with the help of a narrow literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases during the period between 2015 and 2025. General search combinations were used in identifying relevant studies, based on rat lung development, bronchial and vascular architecture, imaging modalities, molecular regulation, and experimental disease models. Articles that used rat lungs in imaging studies, translational experimental reports, and other structurally or mechanistically focused studies were selected, and those that lacked structural or mechanistic relevance were excluded. Citation tracking of important publications was used to add more sources. This method guaranteed the full coverage of developmental, imaging-based, molecular, and pathological factors of rat pulmonary architecture.

Developmental Morphogenesis of Rat Lung Architecture

Embryonic and Postnatal Lung Development

Rats pass through the pseudoglandular, canalicular, saccular, and alveolar phases of lung development,

whereby the vascular and bronchial systems develop simultaneously to create a highly branched respiratory

network. Bifurcation of airways starts at the lung buds and continues with the growing vascular plexus,

which eventually develops into a hierarchical arteriovenous system [21]. Though the imaging techniques

like µCT give insight into development, the fundamental process is the coordinated growth of bronchial

branches and vascular structures that allow efficient respiratory architecture [22]. Models of

cross-species organoid and pluripotent stem cells indicate that cardiopulmonary co-development is

conserved, with epithelial and endothelial differentiation having to proceed in parallel to reach

functional maturation [23]. VEGF is a key mediator of vascular bed development, and VEGF signaling defects

have great consequences on alveolarization and vessel branching [24, 25]. VEGF deficiency or hypoxic

stress impedes the development of the distal vessels' arborization and septation, which supports the

dependence of both epithelial and vascular growth in morphogenesis [26]. Branching of the airways involves

the involvement of fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and its receptor FGFR2b, and the change in these

signals can change vascular alignment indirectly by regulating epithelial geometry [27]. In prenatal and

postnatal stages, epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk is proportionately controlled by signaling pathways,

including SHH, WNT, and TGF-β [28, 29]. Notch-dependent signaling also enhances airway and vascular

patterning through the preservation of coherent growth and the regulation of epithelial cell fate [30].

Integrative studies reveal that airway branching and vascular patterning are mutually instructive

processes, with endothelial cues regulating airway topology and vice versa [31-34]. Collectively, these

processes suggest that the morphogenesis of the rat lung is a highly coordinated process that is

influenced by molecular gradients, juxtacrine signaling, and mechanical forces.

Cellular and Extracellular Matrix Dynamics

Morphogenesis of rat lungs involves the maintenance of constant contact between the mesenchymal and

epithelial cells that form future bronchial and vascular tissues. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions

control the smooth muscle investment, angle of branching, and differentiation based on the reciprocity of

a growth factor, matrix remodeling, and mechanical tension signaling loops [35, 36]. The extracellular

matrix (ECM) is a structural scaffold and a signaling platform that promotes alveolarization and septation

[37]. The adhesion between epithelial stability and basement membrane integrity is mediated by integrin

and ensures structural maturation and controls inflammatory homeostasis [38]. The stabilization of

developing vessels by paracrine signals of pericytes and fibroblasts, the dynamic response of endothelial

cells to matrix stiffness and architecture, controls capillary sprouting and arteriovenous differentiation

[39]. The ECM, which consists of collagens, elastin, fibronectin, and laminin, develops during both

prenatal and postnatal stages to assist in alveolar recoil characteristics and growth, which is necessary

for effective ventilation [40]. On the whole, the ECM dynamics combine with the epithelial and mesenchymal

signaling to develop mechanically stable but flexible airway and vascular systems.

The results of rat development should be viewed with caution since the variation in the pattern of

branching and vascular alignment between strains provides variability in studies [22]. Also, integrative

analyses show that epithelial-endothelial coordination is very context-dependent and thus observations

made with one rat strain cannot necessarily be reliably generalized to other species or experimental

conditions [31].

Coordinated airway and vascular development during different embryonic and postnatal development stages

determines rat lung morphogenesis, which is regulated by reciprocal epithelial-endothelial signaling and

highly controlled molecular pathways that determine patterns of branching and vascular alignment.

Mechanobiological cues, the extracellular matrix, also contribute to structural support and guide

maturation of the alveoli and vascular. The combination of these processes of development forms the

primary bronchial-vascular architecture that forms the basis of subsequent functional performance and

remodeling pathology.

Imaging and Quantitative Approaches

Classical Histomorphometry and Stereology

Histomorphometric and stereological methods have long been used in the quantitative evaluation of lung

structure, which offers objective and reproducible estimates of airway and vascular parameters of fixed

tissue specimens. To close the divide between architectural design and gas-exchange efficiency, first,

stereological models were created to measure the alveolar volume, surface area, and capillary density

[41]. Design-based stereology is still a major method used in the measurement of microvascular and

bronchial architecture of rat lungs and can be reproducibly used in both developmental and pathological

models. The finesse of the stereological concepts of rodents has now allowed the detailed description of

the microvascular branching, the thickness of the vessel walls, and the size of the bronchial lumen in

physiological and disease states [42]. Stereology, when used together with systematic uniform random

sampling, removes the distortions of two-dimensional histology and provides statistically representative

estimates of three-dimensional quantities [43]. In order to improve precision between tissue hierarchies,

recent methods combine computed tomography with histological sections to produce multiscale datasets to be

used in stereological computation [44]. Stereology remains a valid method of measuring vascular

rarefaction, interstitial expansion, and bronchial remodeling in experimental rat preparations and normal

lung tissue [45]. Modern multiresolution workflows can be used to take the classical stereological

paradigm and transform it into a single system of analysis that allows hierarchical measurements across

scales by using macroscopic volumetric data as well as microscale quantification [46]. Even though

classical stereology is still destructive, it is still regarded as the gold standard of volumetric

calibration of digital imaging results in rat morphometric studies [47].

Modern 3D and In vivo Imaging

Recent advances in technology have changed the two-dimensional histology of the lungs into a

three-dimensional volumetric analysis of intact rat lungs, which is dynamic. The micro-computed tomography

(Micro-CT or µCT) enables the determination of airway diameter, vessel density, and branching geometry at

a resolution of micrometers across entire volumes of lungs [48]. Precise reconstruction of the

microvasculature of the lungs can be obtained in case of proper control of perfusion pressures and

contrast enhancement, and almost native visualization of the arterial and venous hierarchies can be

achieved [49]. Optical clearing and light-sheet microscopy can be used as a complement to µCT, allowing

mapping microvascular-bronchial relationships at a fine scale in transparent, fluorescently stained rat

lungs [50]. Improvements in aerosol-based clearing techniques currently allow longitudinal imaging of the

inflammatory and infectious events in vivo with enhanced imaging penetration and temporal

resolution [51]. Multiscale three-dimensional imaging systems combine both the macrovascular and

microvascular data to produce organ-scale views of the bronchial and vascular hierarchies [52].

Computational modeling also improves such datasets through digital reconstruction of vascular networks and

bronchial patterns of branching, which allows simulation of the interactions between hemodynamics and

ventilatory conditions relevant to physiology [53]. These virtual lung models accurately recreate in

vivo mechanical conditions with experimentally obtained values of pulmonary volume, pressure, and

strain [54]. In fetal morphometry and developmental toxicology, it has been shown that volumetric imaging

and µCT are capable of detecting small changes in airway and vascular development, which can be used to

give quantitative measures of translational development [55]. High-resolution imaging, optical clearing,

and computational modeling are a complete paradigm that brings together structural quantification, spatial

organization, and predictive simulation.

Imaging and stereological techniques, although positive, have significant drawbacks. Stereological

estimates are also prone to sampling strategy and inflation bias, which may create systematic variability

among laboratories [43]. Perfusion pressure and uniformity of contrast are the key factors affecting the

accuracy of µCT, which leads to inconsistent visualization of distal vessels across studies [49].

Stereology and µCT are the gold standard of volumetric and vascular reconstruction accuracy, and

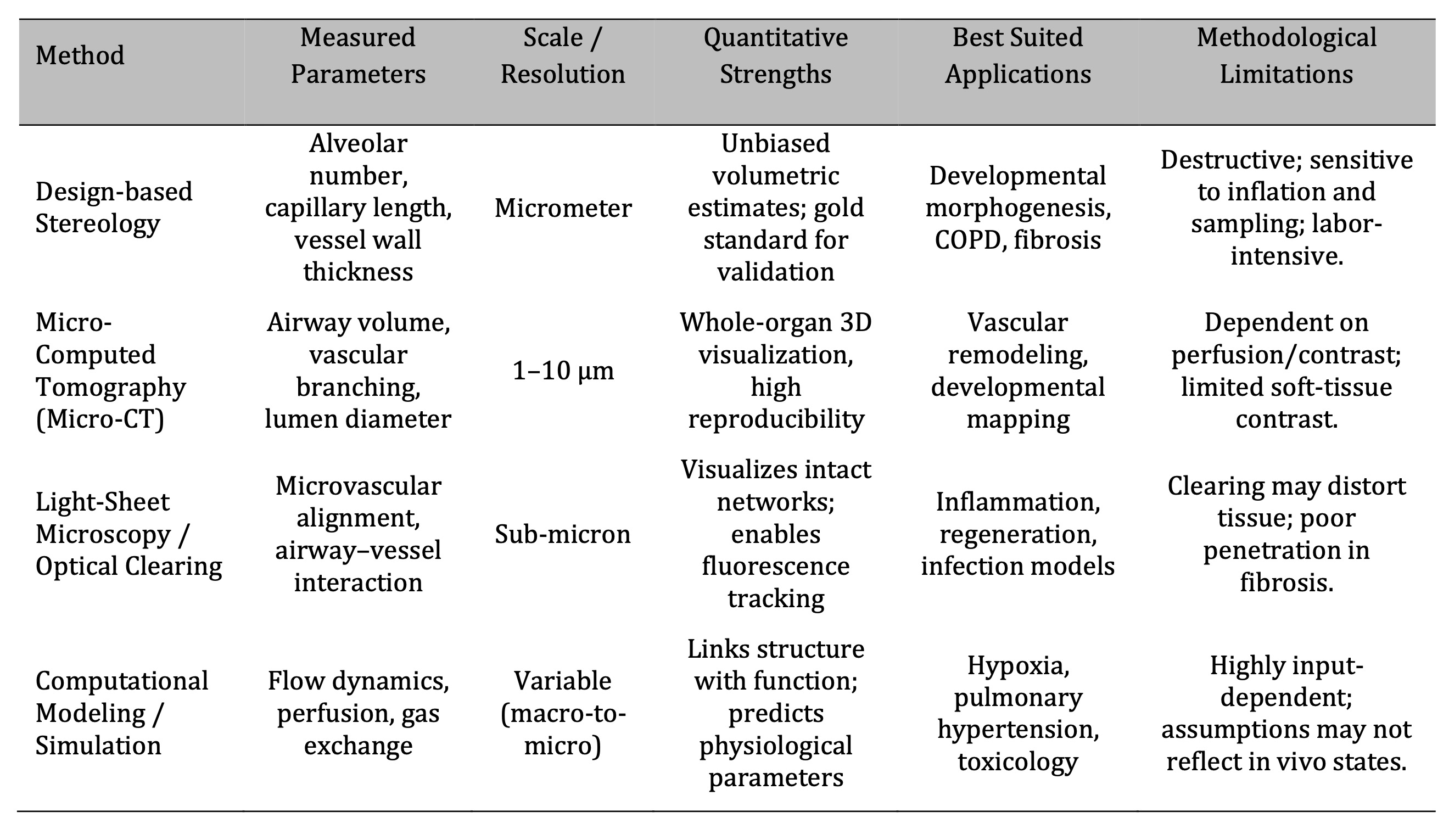

quantitative imaging modalities differ in the resolution of analysis at the morphometric scales (Table 1).

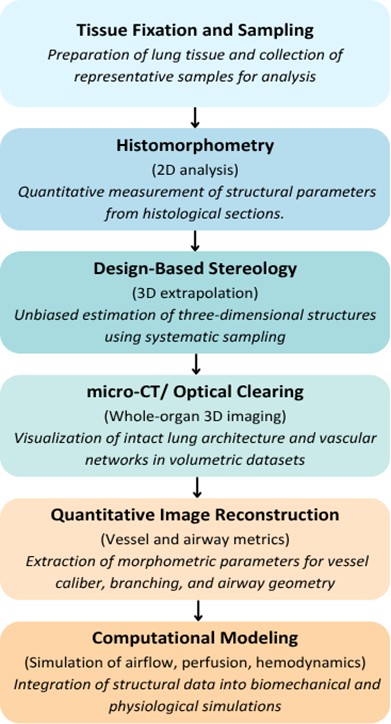

Fig. 1 represents the workflow of the imaging and quantitative methods that were employed to analyze the

morphometry of rat lungs. Fig. 2 [53] illustrates an example of high-resolution whole-lung reconstruction

of a µCT of bronchial vascular architecture of intact rat lungs. The left panel is the horizontal slice of

µCT that illustrates the global airway and parenchymal architecture of the rat lung, and the right one is

the magnified view of the boxed area, which represents the detailed microstructure of the alveoli and

acinar.

Multi-scale reconstruction of rat bronchial and vascular architecture can be done using imaging and

quantitative methods - classical stereology to µCT and light-sheet microscopy. The gold-standard

validation framework is provided by stereology, and the high-resolution structural mapping of organs in a

comprehensive manner is offered by modern 3D imaging. Computational modeling goes a step further to

combine these datasets and simulate physiological interactions, and improve interpretability. These

instruments are collectively a consistent system of quantitative tools necessary to research development,

remodeling, and disease in rat lungs.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Quantitative Imaging and Analytical Techniques in Rat Lung Architecture Studies

Fig. 1: Workflow of Imaging and Quantitative Approaches in Rat Lung Morphometry.

Fig. 2: Micrometer-resolution X-ray micro-CT of an intact post-mortem juvenile rat lung (reproduced from ref. [53], under CC BY 4.0 license).

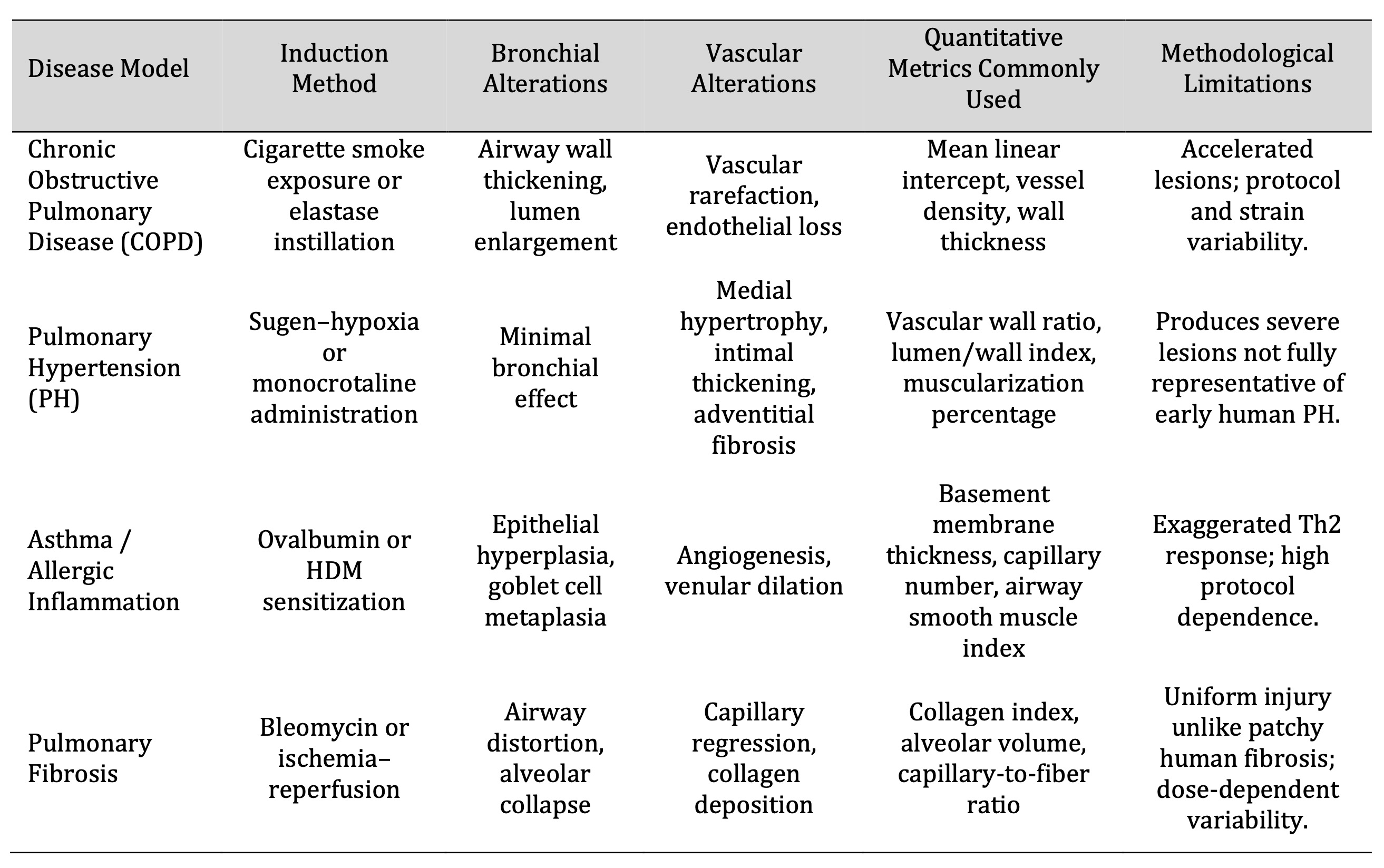

Experimental Models of Lung Diseases in Rats

Models of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Emphysema

The analysis of structural and vascular alterations underlying progressive airflow limitation with the

help of experimental rat models of emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been

critical. Human COPD is characterized by the destruction of the alveoli and small airway remodeling, which

are recapitulated by the classical induction methods, including cigarette smoke or proteolytic agent

exposure [56]. These rats exhibit the progressive emphysematous changes, which, according to longitudinal

modeling, include the quantifiable loss of parenchymal elasticity and capillary rarefaction, which follow

the progression of human disease [57]. Morphometric studies demonstrate that there is an increase in the

size of distal airspaces, alveolar septa become thin, and the surface area of capillaries is reduced,

which increases dead space and reduces the efficiency of gas-exchange [58]. Injury in neonatal and

juvenile rats caused by hyperoxia induces the same structural continuum, alveolar simplification, and

vascular rarefaction occurring concurrently [59]. Combined COPD-cor pulmonale models also enable

concurrent evaluation of right ventricular adaptation and pulmonary vascular remodeling, which enhances

the structure-function relationships with chronic airflow limitation [60]. The characteristic

architectural alterations, including thickening of the small airway walls, loss of the distal vascular

density, and altered smooth-muscle organization, which are highly reminiscent of airway-vascular coupling

disruptions seen in human COPD, are also identified in smoke-exposure models [61]. Taken together, these

rat models are a good representation of the morphometric and hemodynamic characteristics of COPD, which

allows interventions to be controlled to protect airways and vascular integrity.

Pulmonary Hypertension and Vascular Remodeling

The rat model of pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a well-defined model for studying vascular structural

remodeling. Chronic hypoxia or chemical agents like monocrotaline or Sugen cause prolonged increases in

pulmonary arterial pressure, which in turn leads to the medial hypertrophy, adventitial thickening, and

muscularization of the distal arteries [62]. The reversal of neointimal proliferation by therapeutic

studies such as paclitaxel-based interventions demonstrates the structural reversal of neointimal

proliferation, which highlights the usefulness of PH models in testing anti-remodeling strategies [63].

The Sugen-hypoxia model allows cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to be used to allow longitudinal

evaluation of biventricular structural and functional responses, correlating right-heart responses with

pulmonary vascular load [64]. Despite the fact that this model mainly reflects severe pulmonary arterial

hypertension, related parenchymal injury, and mild patterns of emphysema indicates the structural

interaction between vascular and airway compartments in the advanced disease [65]. Collectively, these PH

models offer critical information about the thickening of the vascular, the stiffening of the vessel, and

the hierarchical remodeling of the pulmonary arterial tree.

Asthma and Inflammatory Models

Rat models of asthma and allergic airway inflammation are the focus of structural interaction between

immune activation, angiogenesis, and airway remodeling. Ovalbumin or house-dust-mite antigen sensitization

results in reproducible airway hyperresponsiveness that is associated with vascular proliferation and

deposition of extracellular matrix in the peribronchial region [66]. Histologically, neovascularization,

goblet-cell hyperplasia, and epithelial basement-membrane thickening are always evident, and they

represent the organized remodeling of vascular, mesenchymal, and epithelial compartments [67].

Interventional models of allergic inflammation indicate that structural outcomes, including decreased

peribronchial vessel density or decreased smooth-muscle thickening, can be measured quantitatively in

these models, which validates their usefulness in the testing of remodeling-directed therapies [68]. The

models of asthma also demonstrate the presence of expanded bronchial vascular plexus and the change in

vessel permeability that leads to the thickening of the airway wall and the narrowing of the lumen [69].

Taken together, these inflammatory models offer a reproducible model of evaluation of airway and vascular

remodeling in an allergic state.

Fibrosis and Acute Lung Injury

Experimental models of fibrosis and acute lung injury are essential for understanding the structural

distortion and reparative vascular responses that are related to chronic lung disease. Activation of

macrophages, cytokine release, and matrix deposition in response to exposure to toxicants or hypoxia is

highly reminiscent of human interstitial fibrosis [70]. Experiments of smoke-induced injury indicate that

corticosteroid timing and dose affect vascular remodeling, collagen turnover, and final fibrotic

phenotype, highlighting the structural plasticity of injured lung tissue [71]. Models based on bleomycin

are still the gold standard as they offer quantitative data of anti-fibrotic activity and architectural

recovery [72]. The association between oxidative stress, vascular leakage, and endothelial barrier

disruption is further demonstrated using ischemia-reperfusion injury models, which can be prevented

through antioxidant therapy, including edaravone [73]. Natural and synthetic interventions, such as

resveratrol nano-capsules and crocin, have been demonstrated to inhibit fibrosis, inflammation, and

vascular dysfunction, which contributes to their possible therapeutic significance [74, 75]. These models

taken together describe the cascade of events of epithelial injury, vascular repair, and matrix remodeling

that control chronic fibrotic progression.

Despite the numerous structural parallels of COPD and fibrosis, rat disease models are based on induced

injuries, which may not completely recapitulate the heterogeneous, slow progression of human disease [56].

Equally, fibrosis induced by bleomycin causes homogenous parenchymal damage, unlike the focal and

heterogeneous injury in the clinical presentation [72].

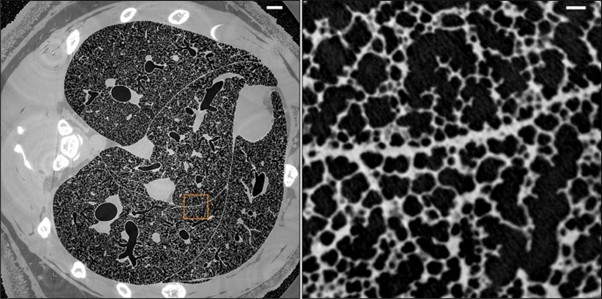

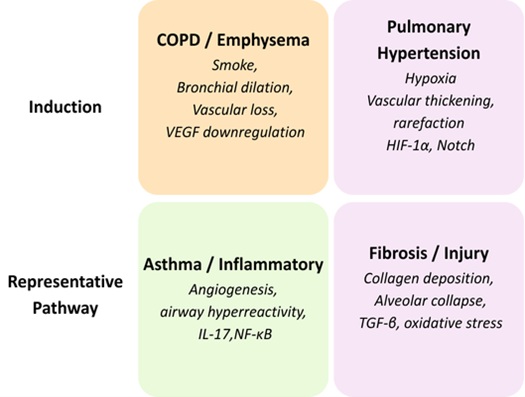

In structural remodeling, several of the conserved signalling cascades integrate fibrotic, inflammatory,

and angiogenesis (Table 2), reflecting the molecular interdependency of the vascular and bronchial

systems. Fig. 3 demonstrates the grouping of experimental rat models and the structural changes that occur

in them.

Rat models of COPD, pulmonary hypertension, asthma, and fibrosis reproduce specific patterns of airway and

vascular remodeling that are highly similar to human disease. Their structural effects, such as

destruction of alveoli, vascular rarefaction, arterial thickening, neovascularization, and matrix

deposition, allow accurate morphometric evaluation in disease conditions. Architectural variations of the

models are also effective in offering a solid platform for assessing treatments that focus on airway and

vascular integrity. These experimental systems as a whole constitute a complete structural toolkit to

study pathological remodeling in the rat lung.

Table 2: Key Molecular Pathways and Signaling Axes Governing Pulmonary Architectural Remodeling in Rats

Fig. 3: Classification of Experimental Rat Models and Associated Structural Alterations.

Molecular Pathways Governing Architectural Remodeling

Key Angiogenic and Morphogenetic Pathways

In the rat lung, morphogenesis of the bronchial and vascular systems is tightly controlled by conserved

molecular pathways incorporating hypoxic, angiogenic, and developmental cues. Notch signaling is a key

orchestrator of endothelial specification and vascular hierarchy, in which it keeps the tip-stalk cell

differentiation balanced in sprouting angiogenesis [76]. VEGF/PI3K/Akt cascade activation restores the

endothelial functional activity and decreases pulmonary arterial thickening in COPD-induced vascular

remodeling, which is associated with metabolic control and angiogenic competence [77]. Hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α (HIF-1α) pathway is an oxygen-sensing regulator that links hypoxic conditions to vascular

growth, and its malfunctioning leads to the excessive muscularization of pulmonary hypertension [78].

Endothelial-derived angiocrine factors also influence epithelial branching and alveolar maturation,

highlighting reciprocal vascular–airway communication during development and repair [79]. Interactions

between PPARγ and Wnt/β-catenin signaling guide epithelial differentiation and vascular alignment, and

imbalances among these networks contribute to pathological architectural remodeling [80]. VEGF, HIF-1α,

Notch, and Wnt signaling constitute an integrated regulatory axis that regulates angiogenesis,

epithelial-vascular interactions, and tissue homeostasis in normal and disease lung [81].

Inflammatory and Oxidative Mechanisms in Vascular Remodeling

Redox-responsive pathways and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are significant regulators of inflammatory and

structural remodeling in rat models of pulmonary disease. Mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial

apoptosis, and perivascular inflammation are sustained by prolonged oxidative stress in pulmonary

hypertension and remodel the vascular wall [82]. Chronic redox imbalance may trigger

endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, leading to adventitial fibrosis and microvascular obliteration,

which resembles human pulmonary pathology [83]. Inflammatory cytokine activation—particularly within the

NF-κB/TNF-α axis—exacerbates vascular injury and promotes smooth-muscle hypertrophy and intimal thickening

in hypoxia-induced models [84]. Chronic hypoxia induces the upregulation of microRNA-150 that suppresses

vascular remodeling through inhibiting profibrotic and inflammatory cascades, which rejuvenate endothelial

functions and pulmonary hemodynamics [85]. All these processes indicate that there is close molecular

interaction between oxidative stress, cytokine release, and regulation by microRNAs in adaptive and

maladaptive remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature.

Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of Remodeling

Genetic and epigenetic changes are increasingly recognized as key determinants in the transition from

reversible injury to chronic pulmonary remodeling. Histone acetylation and methylation control

transcriptional reactions to oxidative injury and vascular pathology, and environmental stressors promote

dynamic histone chromatin remodeling in rat models of fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension [86]. Long

non-coding RNAs and microRNAs have been shown to regulate vascular contractility and endothelial

differentiation, and experimental manipulation of these RNAs has been shown to change the course of

disease in rat pulmonary arterial hypertension models [87]. In chronic thromboembolic pulmonary

hypertension, transcriptomic studies indicate that the patterns of gene-expression differences that

regulate extracellular-matrix turnover, angiogenesis, and inflammation are heritable reprogramming of

vascular and interstitial cell fate [88]. Fibroblast reprogramming studies of rodent tissues have shown

that intermediate trans-endothelial-like states can increase reparative capacity, which can inform us

about the mechanisms underlying structural regeneration [89]. Chromatin data of the rat parenchymal

disease models on a genome-wide scale also show reproducible epigenetic signatures of vascular distortion

and fibrotic development [90]. Taken together, these results indicate that genetic, epigenetic, and

transcriptional regulators combine with environmental and molecular signals to determine the pathway of

pulmonary architectural remodeling.

Although rat models have helped to elucidate many signaling pathways, there are still a number of

translational differences. Hypoxia-regulated HIF-1α signaling differs in magnitude between species,

influencing vascular-proliferative responses [78], while inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB/TNF-α

activation may be exaggerated in rodent models relative to chronic human disease [84].

Angiogenic, inflammatory, and fibrotic responses are interconnected through several conserved signaling

cascades in the process of structural remodeling (Table 3), which indicates the molecular interdependence

of bronchial and vascular systems.

Key molecular pathways—including VEGF, HIF-1α, Notch, and Wnt/β-catenin—form a coordinated regulatory axis

controlling angiogenesis and airway–vascular alignment. Maladaptive vascular remodeling is also further

promoted by oxidative stress, cytokine signaling, and microRNA networks in various models of rat disease.

Long-term changes in vascular and interstitial cell fate are determined by genetic and epigenetic

regulators, including chromatin modulations and non-coding RNAs. A combination of these molecular systems

describes the convergence of the inflammatory, angiogenic, and fibrotic responses to generate the

structural remodeling.

Table 3: Structural Remodeling Patterns Across Experimental Rat Models of Lung Disease

Integrative Translational Perspectives

Translational Relevance of Rat Pulmonary Architecture

The rat lung model has significant translational potential and offers a mechanistic understanding of

clinical importance because it is closely physiologically similar to the human pulmonary system. The

analysis of the single-cell gene expression and remodeling in the rat lungs is comparable to the results

of human pulmonary arterial hypertension, showing that there is a shared vascular pathobiology [91].

Translational fidelity is also confirmed with aerosol-based inhalation studies, whereby the dynamics of

droplet transport, deposition, and clearance scales between rat and human airway geometries can be

predicted [92, 93]. Precision-cut lung slices have demonstrated that rat pulmonary tissue mimics human

xenobiotic enzymatic profiles and thus can be used in preclinical drug-safety testing [94]. Also,

multifaceted models of pulmonary hypertension and right-ventricular remodeling in rats recapitulate

experimentally determined hemodynamic and architectural patterns, which can be used to extrapolate

therapeutic targets and strategies [95]. Taken together, this establishes that the rat offers a

physiologically healthy platform that connects preclinical mechanistic data to human lung pathophysiology.

Integrating Morphometric and Molecular Frameworks for Precision Modeling

The rat lung has turned out to be a useful platform to combine molecular and structural data, which are

fueled by multimodal imaging and omics technologies. Quantitative morphometric analysis, which is coupled

with high-resolution imaging, provides reproducible spatial measures of airways, vessels, and parenchyma

that are translational biomarkers of emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis [96, 97]. Three-dimensional

reconstruction and optical imaging methods directly observe multiscale structural remodeling and also

record molecular correlates of inflammation and tissue repair [98]. Regional density and vascular

tortuosity are imaging biomarkers that have a strong association with histopathological severity in rat

models and parallel imaging phenotypes in human interstitial lung disease [99]. Computational registration

and cross-species anatomical mapping improve comparative knowledge of bronchiolar and lobular structure in

rodents and humans [100]. Transcriptomic analysis of rat and human airway epithelium also shows that there

is a conserved gene-network regulation of epithelial differentiation and immune responses [101, 102]. A

combination of these integrative approaches combines molecular profiling with quantitative morphometry to

produce reproducible, cross-compatible data sets that enhance translational pulmonary modeling.

Computational Extrapolation and Cross-Species Validation

Computational models are increasingly allowing one to extrapolate rat data to human respiratory states.

Now species-agnostic comparisons of lung cell populations can be made using single-cell atlases and

transcriptomic mapping, which can be used to predict species-conserved vascular-signaling and

matrix-remodeling pathways [103, 104]. Simulations in silico are reliable predictors of particle

transport, dose distribution, and deposition efficiency when flow dynamics and airway geometries of rats

are scaled to human conditions [105]. Combining computational results with morphometric and molecular data

can be used to create digital lung twins that can recreate physiologic behavior across species. The use of

these models in comparison to empirical data of rat and human systems improves algorithms to predict gas

exchange, mechanical stress, and drug-absorption profiles. This integration of computational surrogate and

biological validation makes the rat model a predictive translational system rather than a descriptive

experimental system, and makes it more relevant to accurate respiratory research.

Although there are strong parallels in the translation, species-specific differences do not allow direct

extrapolation of rat-based results. Single-cell studies indicate partial but not complete correspondence

of rat and human vascular signaling networks [91], and xenobiotic metabolism, while broadly similar, still

differs in key enzyme pathways relevant for drug-response prediction [94].

Rat lungs exhibit physiological, metabolic, and structural characteristics that are highly similar to

those of the human lungs, which makes them highly translational. A combination of morphometric data and

molecular and imaging-based analyses would allow cross-species biomarkers of structural lung disease to be

reproducible. Predictions of gas exchange, airflow dynamics, and drug delivery are also enhanced with the

help of computational scaling and digital models of lung twins. Collectively, these strategies make the

rat a strong translational tool between the experimental results and the human pulmonary pathophysiology.

Emerging Technologies in Pulmonary Structural Analysis

Advanced Imaging and Quantitative Modeling

Recent breakthroughs in quantitative modeling and computational imaging have revolutionized the study of

pulmonary structure and vascular remodeling using rat models, where µCT imaging can be used to visualize

microvascular adaptation to hemodynamic or hypoxic stress with high spatial resolution, and the patterns

of remodeling heterogeneity can be used to better understand cardiopulmonary coupling in pulmonary

hypertension [107]. Computational models that take morphometric inputs reproduce airflow distribution,

pressure gradient, and vascular resistance through fluid dynamics and tissue deformation simulation of the

rat lung [108]. Such combined approaches combine both anatomical measurements and functional performance

to improve the accuracy of preclinical disease modeling and therapeutic assessment.

Bioengineered Lung Models and Translational Interfaces

Microengineered bio-platforms have become capable of recreating key rat lung biomechanical and

microvascular physiological features. Lung-on-chip and 3D-printed scaffolds are alveolar-capillary

interfaces re-engineered with microfluidic channels covered with epithelial and endothelial cells, and

allow dynamic modeling of inflammatory, fibrotic, or mechanical stimuli [109]. These devices can

manipulate airflow, perfusion, tissue stretch, and gas-exchange parameters in a controlled manner, usually

based on imaging-based templates of rat lung architecture. These bioengineered systems can be used to

support physiologically relevant testbeds, which can be used to further preclinical validation of

molecular and pharmacologic intervention and translational alignment between human pathology and rat in

vivo experiments.

Integrative Systems Biology and Predictive Analytics

The imaging, molecular, and computational datasets are becoming more and more integrated into systems

biology approaches to produce predictive frameworks of pulmonary remodeling. Data integration using

artificial intelligence links structural, transcriptional, and metabolic networks together, providing a

mechanistic understanding of inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis [110]. These models integrate

multi-omics data with morphometric data to project architectural changes in both development and disease.

The integration of digital morphometry and systems-level models provides a platform of accurate and

multiscale predictions of lung behavior and facilitates the design of interventions.

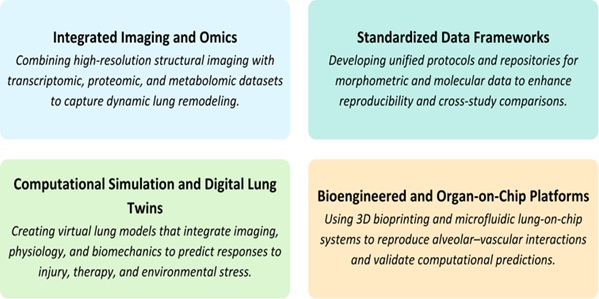

Future Directions in Technological Integration

Further convergence of systems biology, computational modeling, and state-of-the-art imaging will be

useful in future pulmonary structural studies. Dynamic analysis of the co-evolution of airway branching

and vascular remodeling throughout disease progression will be possible using high-resolution

visualization with biomechanical and molecular data. Creating open-access, standardized morphometric and

multi-omics data repositories will enhance reproducibility and translational applicability between rat

models and human experiments. The combination of digital simulations and bioengineered organ-level systems

into predictive multiscale models is the next step in the analysis of pulmonary structure, which

correlates structure, function, and molecular regulation at never-before-seen levels. The directions in

this field are new and summarized in Fig. 4.

New technologies are still limited to methodological inconsistency, with µCT segmentation and

quantification being reliant on the calibration of scanners and perfusion status [107], and computational

simulations being susceptible to minor morphometric errors, which can cause a considerable change in the

distribution of predicted airflow or pressure [108].

The high-precision analysis of rat lung structure is now possible due to the use of advanced µCT imaging,

computational modeling, and multiscale reconstruction. Physiologic microenvironments, such as lung-on-chip

systems, are bioengineered platforms that are used to improve preclinical modeling and translational

testing. The integration of morphometric and molecular data by systems biology and AI also produces

predictive and cross-scale models of lung remodeling. Further advancements will be based on integrating

digital simulations, high-resolution images, and open-access data to enhance translational relevance.

Fig. 4: Future Directions in Pulmonary Structural Research.

Conclusion

The rat lung is an immensely informative model for studying the coordinated architecture of bronchial and vascular systems throughout development and pathology. The development of imaging, stereology, and molecular profiling has enhanced the knowledge of the interaction and remodeling of these compartments in diseases like fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, and airway injury. The combination of morphometric accuracy with molecular and computational data is now used to improve the predictive and translational usefulness of rat studies. Further advancements in the standardization of imaging, multiscale data analysis, and analytical processes will enhance the usefulness of this model as an essential linkage between experimental discovery and human pulmonary biology.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Department of Cytology, Embryology, and Histology; Department of Pharmacognosy as well as the Department of Human Anatomy and Medical Terminology at Azerbaijan Medical University, Baku, for providing institutional assistance and access to academic resources. The authors also extend their appreciation to colleagues whose insights and constructive discussions contributed to the refinement of this review.

Author Contributions

Aliyarbayova Aygun Aliyar: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing– original draft, Correspondence;

Aliyeva Sanam Eldar: Literature review, Critical evaluation of studies, Writing –review & editing ;

Shukurova Ayten Sadig: Thematic synthesis, Manuscript organization, Editing. Gasimova Tarana Mubariz:

Conceptual input, Structural refinement, Proofreading; Mustafayeva Nigar Adil: Review of recent

literature, Reference verification, Editing; AliyevaSabina Aydın: Manuscript formatting, Visualization,

Proofreading.

Funding Sources

This review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or

not-for-profit sectors.

Statement of Ethics

This article is based on previously published studies and does not involve any new experiments with human

participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this review article.

References

| 1 | Mühlfeld C. Stereology and three-dimensional reconstructions to analyze the pulmonary vasculature.

Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2021 Aug;156(2):83-93.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-021-02013-9 |

| 2 | Hopkins SR, Stickland MK. The pulmonary vasculature. InSeminars in respiratory and critical care

medicine 2023 Oct (Vol. 44, No. 05, pp. 538-554). Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc..

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1770059 |

| 3 | Zhao S, Cui J, Wang Y, Xu D, Su Y, Ma J, Gong X, Bai W, Wang J, Cao R. Three-dimensional

visualization of the lymphatic, vascular and neural network in rat lung by confocal microscopy.

Journal of Molecular Histology. 2023 Dec;54(6):715-23.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10735-023-10160-7 |

| 4 | Jones MR, Chong L, Bellusci S. Fgf10/Fgfr2b signaling orchestrates the symphony of molecular,

cellular, and physical processes required for harmonious airway branching morphogenesis. Frontiers

in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021 Jan 12;8:620667.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.620667 |

| 5 | El Agha E, Iber D, Warburton D. Branching Morphogenesis During Embryonic Lung Development.

Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021 Jul 12;9:728954.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.728954 |

| 6 | Hirashima T, Matsuda M. ERK-mediated curvature feedback regulates branching morphogenesis in lung

epithelial tissue. Current Biology. 2024 Feb 26;34(4):683-96.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.12.049 |

| 7 | Lang C, Conrad L, Iber D. Organ-specific branching morphogenesis. Frontiers in Cell and

Developmental Biology. 2021 Jun 7;9:671402.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.671402 |

| 8 | Cantor, J. (2025). Rodent Models of Lung Disease: A Road Map for Translational Research.

International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(17), 8386.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26178386 |

| 9 | Haberthür D, Yao E, Barré SF, Cremona TP, Tschanz SA, Schittny JC. Pulmonary acini exhibit complex

changes during postnatal rat lung development. PLoS One. 2021 Nov 8;16(11):e0257349.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257349 |

| 10 | Jasińska-Stroschein M. An updated review of experimental rodent models of pulmonary hypertension

and left heart disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2024 Jan 8;14:1308095.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1308095 |

| 11 | Napieczyńska, H., Kedziora, S. M., Haase, N., Müller, D. N., Heuser, A., Dechend, R., & Kräker, K.

(2024). μCT imaging of a multi-organ vascular fingerprint in rats. PLoS One, 19(10), e0308601.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308601 |

| 12 | Rekabdar T, Yousefi M, Masoudifard M, Zehtabvar O, Ahmadpanahi SJ. Computed Tomographic Anatomy

and Topography of the Lower Respiratory System of the Mature Rat (Rattus norvegicus). Archives of

Razi Institute. 2024 Oct 31;79(5):981.

https://doi.org/10.32592/ARI.2024.79.5.981 |

| 13 | Mühlfeld C, Schipke J, Labode J, Ochs M. Targeted stereology: sampling heterogeneously distributed

structures and lesions in the lung. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular

Physiology. 2024 Aug 1;327(2):L258-65.

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00321.2023 |

| 14 | Wang A, Ali A, Keshavjee S, Liu M, Cypel M. Ex vivo lung perfusion for donor lung assessment and

repair: a review of translational interspecies models. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular

and Molecular Physiology. 2020 Dec 1;319(6):L932-40.

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00295.2020 |

| 15 | Susaki EA. Unlocking the potential of large-scale 3D imaging with tissue clearing techniques.

Microscopy. 2025 Jun 26;74(3):179-88.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jmicro/dfae046 |

| 16 | Xu X, Su J, Zhu R, Li K, Zhao X, Fan J, Mao F. From morphology to single-cell molecules:

high-resolution 3D histology in biomedicine. Molecular Cancer. 2025 Mar 3;24(1):63.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-025-02240-x |

| 17 | Iber D. The control of lung branching morphogenesis. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2021

Jan 1;143:205-37.

https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2021.02.002 |

| 18 | Feng T, Cao J, Ma X, Wang X, Guo X, Yan N, Fan C, Bao S, Fan J. Animal models of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine. 2024 Oct 24;11:1474870.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1474870 |

| 19 | Ochs M, Schipke J. A short primer on lung stereology. Respiratory Research. 2021 Nov 27;22(1):305.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01899-2 |

| 20 | Brenna C, Simioni C, Varano G, Conti I, Costanzi E, Melloni M, Neri LM. Optical tissue clearing

associated with 3D imaging: application in preclinical and clinical studies. Histochemistry and Cell

Biology. 2022 May;157(5):497-511.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-022-02081-5 |

| 21 | Burri PH. Structural aspects of prenatal and postnatal development and growth of the lung. InLung

growth and development 2024 Nov 1 (pp. 1-36). CRC Press.

https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003574026-1 |

| 22 | Markel M, Ginzel M, Peukert N, Schneider H, Haak R, Mayer S, Suttkus A, Lacher M, Kluth D,

Gosemann JH. High resolution three‐dimensional imaging and measurement of lung, heart, liver, and

diaphragmatic development in the fetal rat based on micro‐computed tomography (micro‐CT). Journal of

Anatomy. 2021 Apr;238(4):1042-54.

https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13355 |

| 23 | Ng WH, Johnston EK, Tan JJ, Bliley JM, Feinberg AW, Stolz DB, Sun M, Wijesekara P, Hawkins F,

Kotton DN, Ren X. Recapitulating human cardio-pulmonary co-development using simultaneous

multilineage differentiation of pluripotent stem cells. Elife. 2022 Jan 12;11:e67872.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.67872 |

| 24 | Addis DR, Lambert JA, Ren C, Doran S, Aggarwal S, Jilling T, Matalon S. Vascular Endothelial

Growth Factor‐121 Administration Mitigates Halogen Inhalation‐Induced Pulmonary Injury and Fetal

Growth Restriction in Pregnant Mice. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020 Feb

4;9(3):e013238.

https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.013238 |

| 25 | Myint MZ, Jia J, Adlat S, Oo ZM, Htoo H, Hayel F, Chen Y, Bah FB, Sah RK, Bahadar N, Chan MK.

Effect of low VEGF on lung development and function. Transgenic Research. 2021 Feb;30(1):35-50.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11248-020-00223-w |

| 26 | Aydin E, Levy B, Oria M, Nachabe H, Lim FY, Peiro JL. Optimization of pulmonary vasculature

tridimensional phenotyping in the rat fetus. Scientific Reports. 2019 Feb 4;9(1):1244.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37906-8 |

| 27 | Chao CM, Moiseenko A, Kosanovic D, Rivetti S, El Agha E, Wilhelm J, Kampschulte M, Yahya F,

Ehrhardt H, Zimmer KP, Barreto G. Impact of Fgf10 deficiency on pulmonary vasculature formation in a

mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Human molecular genetics. 2019 May 1;28(9):1429-44.

https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy439 |

| 28 | Warburton D. Conserved Mechanisms in the Formation of the Airways and Alveoli of the Lung.

Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021 Jun 15;9:662059.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.662059 |

| 29 | Lecarpentier Y, Gourrier E, Gobert V, Vallée A. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Crosstalk between

PPARγ, WNT/β-Catenin and TGF-β pathways; the potential therapeutic role of PPARγ agonists. Frontiers

in pediatrics. 2019 May 3;7:176.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00176 |

| 30 | Kiyokawa H, Morimoto M. Notch signaling in the mammalian respiratory system, specifically the

trachea and lungs, in development, homeostasis, regeneration, and disease. Development, Growth &

Differentiation. 2020 Jan;62(1):67-79.

https://doi.org/10.1111/dgd.12628 |

| 31 | Zepp JA, Morrisey EE. Cellular crosstalk in the development and regeneration of the respiratory

system. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2019 Sep;20(9):551-66.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0141-3 |

| 32 | Song L, Li K, Chen H, Xie L. Cell cross-talk in alveolar microenvironment: from lung injury to

fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2024 Jul;71(1):30-42.

https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2023-0426TR |

| 33 | Stoilova T, Ruhrberg C. Lung blood and lymphatic vascular development. Lung Stem Cells in

Development, Health and Disease (ERS Monograph). Sheffield, European Respiratory Society. 2021 Apr

1:31-43.

https://doi.org/10.1183/2312508X.10008920 |

| 34 | Kina YP, Khadim A, Seeger W, El Agha E. The lung vasculature: a driver or passenger in lung

branching morphogenesis?. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021 Jan 14;8:623868.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.623868 |

| 35 | Shannon JM, Deterding RR. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in lung development. InLung growth

and development 2024 Nov 1 (pp. 81-118). CRC Press.

https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003574026-4 |

| 36 | Sutlive J, Xiu H, Chen Y, Gou K, Xiong F, Guo M, Chen Z. Generation, transmission, and regulation

of mechanical forces in embryonic morphogenesis. Small. 2022 Feb;18(6):2103466.

https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202103466 |

| 37 | Ito JT, Lourenço JD, Righetti RF, Tibério IF, Prado CM, Lopes FD. Extracellular matrix component

remodeling in respiratory diseases: what has been found in clinical and experimental studies?.

Cells. 2019 Apr 11;8(4):342.

https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8040342 |

| 38 | Plosa EJ, Benjamin JT, Sucre JM, Gulleman PM, Gleaves LA, Han W, Kook S, Polosukhin VV, Haake SM,

Guttentag SH, Young LR. β1 Integrin regulates adult lung alveolar epithelial cell inflammation. JCI

insight. 2020 Jan 30;5(2):e129259.

https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.129259 |

| 39 | Roman J. Cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions in development of the lung vasculature. InLung

growth and development 2024 Nov 1 (pp. 365-400). CRC Press.

https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003574026-13 |

| 40 | Crouch EC, Mecham RP, Davila RM, Noguchi A. Collagens and elastic fiber proteins in lung

development. InLung growth and development 2024 Nov 1 (pp. 327-364). CRC Press.

https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003574026-12 |

| 41 | Tongpob Y, Xia S, Wyrwoll C, Mehnert A. Quantitative characterization of rodent feto-placental

vasculature morphology in micro-computed tomography images. Computer Methods and Programs in

Biomedicine. 2019 Oct 1;179:104984.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.104984 |

| 42 | Zakaria DM, Zahran NM, Arafa SA, Mehanna RA, Abdel-Moneim RA. Histological and physiological

studies of the effect of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on bleomycin induced lung

fibrosis in adult albino rats. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. 2021 Feb;18(1):12741.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13770-020-00294-0 |

| 43 | Debiane L, Reitzel R, Rosenblatt J, Gagea M, Chavez MA, Adachi R, Grosu HB, Sheshadri A, Hill LR,

Raad I, Ost DE. A design-based stereologic method to quantify the tissue changes associated with a

novel drug-eluting tracheobronchial stent. Respiration. 2019 Jul 15;98(1):60-9.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000496152 |

| 44 | Knudsen L, Brandenberger C, Ochs M. Stereology as the 3D tool to quantitate lung architecture.

Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2021 Feb;155(2):163-81.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-020-01927-0 |

| 45 | Sarabia-Vallejos MA, Ayala-Jeria P, Hurtado DE. Three-dimensional whole-organ characterization of

the regional alveolar morphology in normal murine lungs. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021 Dec

8;12:755468.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.755468 |

| 46 | Vasilescu DM, Phillion AB, Kinose D, Verleden SE, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden GM, Van Raemdonck D,

Stevenson CS, Hague CJ, Han MK, Cooper JD. Comprehensive stereological assessment of the human lung

using multiresolution computed tomography. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2020 Jun 1;128(6):1604-16.

https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00803.2019 |

| 47 | Hussain S, Mubeen I, Ullah N, Shah SS, Khan BA, Zahoor M, Ullah R, Khan FA, Sultan MA. Modern

diagnostic imaging technique applications and risk factors in the medical field: a review. BioMed

research international. 2022;2022(1):5164970.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5164970 |

| 48 | Deng Y, Rowe KJ, Chaudhary KR, Yang A, Mei SH, Stewart DJ. Optimizing imaging of the rat pulmonary

microvasculature by micro-computed tomography. Pulmonary circulation. 2019

Oct;9(4):2045894019883613.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2045894019883613 |

| 49 | Nicolas N, Dinet V, Roux E. 3D imaging and morphometric descriptors of vascular networks on

optically cleared organs. IScience. 2023 Oct 20;26(10).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108007 |

| 50 | Wu YC, Moon HG, Bindokas VP, Phillips EH, Park GY, Lee SS. Multiresolution 3D optical mapping of

immune cell infiltrates in mouse asthmatic lung. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular

Biology. 2023 Jul;69(1):13-21.

https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2022-0353MA |

| 51 | Bucharskaya AB, Yanina IY, Atsigeida SV, Genin VD, Lazareva EN, Navolokin NA, Dyachenko PA,

Tuchina DK, Tuchina ES, Genina EA, Kistenev YV. Optical clearing and testing of lung tissue using

inhalation aerosols: prospects for monitoring the action of viral infections. Biophysical Reviews.

2022 Aug;14(4):1005-22.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-022-00991-1 |

| 52 | Tielemans B, Marain NF, Kerstens A, Peredo N, Coll‐Lladó M, Gritti N, de Villemagne P, Dorval P,

Geudens V, Orlitová M, Munck S. Multiscale Three‐Dimensional Evaluation and Analysis of Murine Lung

Vasculature From Macro‐to Micro‐Structural Level. Pulmonary Circulation. 2025 Jan;15(1):e70038.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pul2.70038 |

| 53 | Borisova E, Lovric G, Miettinen A, Fardin L, Bayat S, Larsson A, Stampanoni M, Schittny JC,

Schlepütz CM. Micrometer-resolution X-ray tomographic full-volume reconstruction of an intact

post-mortem juvenile rat lung. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2021 Feb;155(2):215-26.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-020-01868-8 |

| 54 | Badrou A, Mariano CA, Ramirez GO, Shankel M, Rebelo N, Eskandari M. Towards constructing a

generalized structural 3D breathing human lung model based on experimental volumes, pressures, and

strains. PLoS computational biology. 2025 Jan 13;21(1):e1012680.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012680 |

| 55 | Ying X, Barlow NJ, Tatiparthi A. Micro-CT and volumetric imaging in developmental toxicology.

InReproductive and developmental toxicology 2022 Jan 1 (pp. 1261-1285). Academic Press.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-89773-0.00063-1 |

| 56 | Liang GB, He ZH. Animal models of emphysema. Chinese medical journal. 2019 Oct 20;132(20):2465-75.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000469 |

| 57 | Young AL, Bragman FJ, Rangelov B, Han MK, Galbán CJ, Lynch DA, Hawkes DJ, Alexander DC, Hurst JR.

Disease progression modeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of

respiratory and critical care medicine. 2020 Feb 1;201(3):294-302.

|

| 58 | Yang Y, Di T, Zhang Z, Liu J, Fu C, Wu Y, Bian T. Dynamic evolution of emphysema and airway

remodeling in two mouse models of COPD. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2021 Apr 26;21(1):134.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01456-z |

| 59 | Greco F, Wiegert S, Baumann P, Wellmann S, Pellegrini G, Cannizzaro V. Hyperoxia-induced lung

structure-function relation, vessel rarefaction, and cardiac hypertrophy in an infant rat model.

Journal of translational medicine. 2019 Mar 18;17(1):91.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1843-1 |

| 60 | Ma Z, Tong S, Huang Y, Wang N, Chen G, Bai Q, Deng J, Zhou L, Luo Q, Wang J, Lu W. Development and

Characterization of a Novel Rat Model for Emulating Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Associated

Cor Pulmonale. The American Journal of Pathology. 2025 May 1;195(5):831-44.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2025.01.003 |

| 61 | Upadhyay P, Wu CW, Pham A, Zeki AA, Royer CM, Kodavanti UP, Takeuchi M, Bayram H, Pinkerton KE.

Animal models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B. 2023 Jul 4;26(5):275-305.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2023.2208886 |

| 62 | Jia Z, Wang S, Yan H, Cao Y, Zhang X, Wang L, Zhang Z, Lin S, Wang X, Mao J. Pulmonary vascular

remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023 Feb 19;13(2):366.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13020366 |

| 63 | Zhao J, Yang M, Wu X, Yang Z, Jia P, Sun Y, Li G, Xie L, Liu B, Liu H. Effects of paclitaxel

intervention on pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats with pulmonary hypertension. Experimental and

therapeutic medicine. 2019 Feb 1;17(2):1163-70.

|

| 64 | Jayasekera G, Wilson KS, Buist H, Woodward R, Uckan A, Hughes C, Nilsen M, Church AC, Johnson MK,

Gallagher L, Mullin J. Understanding longitudinal biventricular structural and functional changes in

a pulmonary hypertension Sugen-hypoxia rat model by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Pulmonary

Circulation. 2020 Jan;10(1):2045894019897513.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2045894019897513 |

| 65 | Bogaard HJ, Legchenko E, Chaudhary KR, Sun XQ, Stewart DJ, Hansmann G. Emphysema Is-at the

Most-Only a Mild Phenotype in the Sugen/Hypoxia Rat Model of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension.

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2019 Dec 1;200(11):1447-50.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201906-1200LE |

| 66 | Périz M, Pérez-Cano FJ, Rodríguez-Lagunas MJ, Cambras T, Pastor-Soplin S, Best I, Castell M,

Massot-Cladera M. Development and characterization of an allergic asthma rat model for

interventional studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 May 28;21(11):3841.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113841 |

| 67 | Savin IA, Zenkova MA, Sen'kova AV. Bronchial asthma, airway remodeling and lung fibrosis as

successive steps of one process. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023 Nov

7;24(22):16042.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242216042 |

| 68 | Dos Santos TM, Righetti RF, Rezende BG, Campos EC, Camargo LD, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Fukuzaki S,

Prado CM, Leick EA, Martins MA, Tibério IF. Effect of anti-IL17 and/or Rho-kinase inhibitor

treatments on vascular remodeling induced by chronic allergic pulmonary inflammation. Therapeutic

Advances in Respiratory Disease. 2020 Dec;14:1753466620962665.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1753466620962665 |

| 69 | Hall RD, Le TM, Haggstrom DE, Gentzler RD. Angiogenesis inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Translational lung cancer research. 2015 Oct;4(5):515.

|

| 70 | Laskin DL, Malaviya R, Laskin JD. Role of macrophages in acute lung injury and chronic fibrosis

induced by pulmonary toxicants. Toxicological Sciences. 2019 Apr 1;168(2):287-301.

https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfy309 |

| 71 | Song LC, Chen XX, Meng JG, Hu M, Huan JB, Wu J, Xiao K, Han ZH, Xie LX. Effects of different

corticosteroid doses and durations on smoke inhalation-induced acute lung injury and pulmonary

fibrosis in the rat. International immunopharmacology. 2019 Jun 1;71:392-403.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.03.051 |

| 72 | Fragni D. Identification of novel readouts to assess anti-fibrotic efficacy of new compounds in a

bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model.

|

| 73 | Kassab AA, Aboregela AM, Shalaby AM. Edaravone attenuates lung injury in a hind limb

ischemia-reperfusion rat model: a histological, immunohistochemical and biochemical study. Annals of

Anatomy-Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2020 Mar 1;228:151433.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2019.151433 |

| 74 | Zaghloul MS, Said E, Suddek GM, Salem HA. Crocin attenuates lung inflammation and pulmonary

vascular dysfunction in a rat model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Life sciences. 2019 Oct

15;235:116794.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116794 |

| 75 | Albanawany NM, Samy DM, Zahran N, El-Moslemany RM, Elsawy SM, Abou Nazel MW. Histopathological,

physiological and biochemical assessment of resveratrol nanocapsules efficacy in bleomycin-induced

acute and chronic lung injury in rats. Drug Delivery. 2022 Dec 31;29(1):2592-608.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2022.2105445 |

| 76 | Akil A, Gutiérrez-García AK, Guenter R, Rose JB, Beck AW, Chen H, Ren B. Notch signaling in

vascular endothelial cells, angiogenesis, and tumor progression: an update and prospective.

Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2021 Feb 16;9:642352.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.642352 |

| 77 | Zhang L, Tian Y, Zhao P, Jin F, Miao Y, Liu Y, Li J. Electroacupuncture attenuates pulmonary

vascular remodeling in a rat model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via the VEGF/PI3K/Akt

pathway. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2022 Aug;40(4):389-400.

https://doi.org/10.1177/09645284221078873 |

| 78 | Liu P, Gu Y, Luo J, Ye P, Zheng Y, Yu W, Chen S. Inhibition of Src activation reverses pulmonary

vascular remodeling in experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension via Akt/mTOR/HIF-1< alpha>

signaling pathway. Experimental cell research. 2019 Jul 1;380(1):36-46.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.02.022 |

| 79 | Bishop D, Schwarz Q, Wiszniak S. Endothelial-derived angiocrine factors as instructors of

embryonic development. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2023 Jun 29;11:1172114.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1172114 |

| 80 | Vallee A, Lecarpentier Y, Vallee JN. Interplay of opposing effects of the WNT/β-Catenin pathway

and PPARγ and implications for SARS-CoV2 treatment. Frontiers in immunology. 2021 Apr 13;12:666693.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.666693 |

| 81 | Yan T, Shi J. Angiogenesis and EMT regulators in the tumor microenvironment in lung cancer and

immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024 Dec 16;15:1509195.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1509195 |

| 82 | Kura B, Szeiffova Bacova B, Kalocayova B, Sykora M, Slezak J. Oxidative stress-responsive

microRNAs in heart injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 Jan 5;21(1):358.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010358 |

| 83 | Mikhael M, Makar C, Wissa A, Le T, Eghbali M, Umar S. Oxidative stress and its implications in the

right ventricular remodeling secondary to pulmonary hypertension. Frontiers in Physiology. 2019 Sep

24;10:1233.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01233 |

| 84 | Liu WY, Wang L, Lai YF. Hepcidin protects pulmonary artery hypertension in rats by activating

NF-κB/TNF-α pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019 Jan 1;23(17):7573-81.

|

| 85 | Li Y, Ren W, Wang X, Yu X, Cui L, Li X, Zhang X, Shi B. MicroRNA-150 relieves vascular remodeling

and fibrosis in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019 Jan

1;109:1740-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.058 |

| 86 | Ji X, Yue H, Ku T, Zhang Y, Yun Y, Li G, Sang N. Histone modification in the lung injury and

recovery of mice in response to PM2 5 exposure. Chemosphere. 2019 Apr 1;220:127-36.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.079 |

| 87 | Wołowiec Ł, Mędlewska M, Osiak J, Wołowiec A, Grześk E, Jaśniak A, Grześk G. MicroRNA and lncRNA

as the future of pulmonary arterial hypertension treatment. International journal of molecular

sciences. 2023 Jun 4;24(11):9735.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119735 |

| 88 | Vachrushev NS, Shilenko LA, Karpov AA, Ivkin DY, Galagudza MM, Kostareva AA, Kalinina OV.

Differential Gene Expression in the Lungs of Rats with Experimental Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary

Hypertension. Journal of Evolutionary Biochemistry and Physiology. 2025 Jul;61(4):1025-38.

https://doi.org/10.1134/S0022093025040076 |

| 89 | Mathison M, Sanagasetti D, Singh VP, Pugazenthi A, Pinnamaneni JP, Ryan CT, Yang J, Rosengart TK.

Fibroblast transition to an endothelial "trans" state improves cell reprogramming efficiency.

Scientific Reports. 2021 Nov 19;11(1):22605.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02056-x |

| 90 | Avci E, Sarvari P, Savai R, Seeger W, Pullamsetti SS. Epigenetic mechanisms in parenchymal lung

diseases: bystanders or therapeutic targets?. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022 Jan

4;23(1):546.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010546 |

| 91 | Hong J, Arneson D, Umar S, Ruffenach G, Cunningham CM, Ahn IS, Diamante G, Bhetraratana M, Park

JF, Said E, Huynh C. Single-cell study of two rat models of pulmonary arterial hypertension reveals

connections to human pathobiology and drug repositioning. American journal of respiratory and

critical care medicine. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):1006-22.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202006-2169OC |

| 92 | Hayati H, Feng Y, Hinsdale M. Inter-species variabilities of droplet transport, size change, and

deposition in human and rat respiratory systems: An in silico study. Journal of aerosol science.

2021 May 1;154:105761.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2021.105761 |

| 93 | Corley RA, Kuprat AP, Suffield SR, Kabilan S, Hinderliter PM, Yugulis K, Ramanarayanan TS. New

approach methodology for assessing inhalation risks of a contact respiratory cytotoxicant:

Computational fluid dynamics-based aerosol dosimetry modeling for cross-species and in vitro

comparisons. Toxicological Sciences. 2021 Aug 1;182(2):243-59.

https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfab062 |

| 94 | Yilmaz Y, Williams G, Walles M, Manevski N, Krähenbühl S, Camenisch G. Comparison of rat and human

pulmonary metabolism using precision-cut lung slices (PCLS). Drug metabolism letters. 2019 Apr

1;13(1):53-63.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1872312812666181022114622 |

| 95 | Boucherat O, Agrawal V, Lawrie A, Bonnet S. The latest in animal models of pulmonary hypertension

and right ventricular failure. Circulation Research. 2022 Apr 29;130(9):1466-86.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319971 |

| 96 | Hayati H, Feng Y. A precise scale-up method to predict particle delivered dose in a human

respiratory system using rat deposition data: An in silico study. InFrontiers in Biomedical Devices

2020 Apr 6 (Vol. 83549, p. V001T07A005). American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

https://doi.org/10.1115/DMD2020-9060 |

| 97 | Persson IM, Bozovic G, Westergren-Thorsson G, Enes SR. Spatial lung imaging in clinical and

translational settings. Breathe. 2024 Oct 1;20(3).

https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0224-2023 |

| 98 | Nizamoglu M, Joglekar MM, Almeida CR, Callerfelt AK, Dupin I, Guenat OT, Henrot P, Van Os L, Otero

J, Elowsson L, Farre R. Innovative three-dimensional models for understanding mechanisms underlying

lung diseases: powerful tools for translational research. European Respiratory Review. 2023 Jul

26;32(169).

https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0042-2023 |

| 99 | Mahmutovic Persson I, Falk Håkansson H, Örbom A, Liu J, von Wachenfeldt K, Olsson LE. Imaging

biomarkers and pathobiological profiling in a rat model of drug-induced interstitial lung disease

induced by bleomycin. Frontiers in Physiology. 2020 Jun 19;11:584.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00584 |

| 100 | Umeda Y, Izawa T, Kazama K, Arai S, Kamiie J, Nakamura S, Hano K, Takasu M, Hirata A,

Rittinghausen S, Yamano S. Comparative anatomy of respiratory bronchioles and lobular structures in

mammals. Journal of Toxicologic Pathology. 2025;38(2):113-29.

https://doi.org/10.1293/tox.2024-0071 |

| 101 | Gui B, Wang Q, Wang J, Li X, Wu Q, Chen H. Cross-species comparison of airway epithelium

transcriptomics. Heliyon. 2024 Oct 15;10(19).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38259 |

| 102 | Pennitz P, Kirsten H, Friedrich VD, Wyler E, Goekeri C, Obermayer B, Heinz GA, Mashreghi MF,

Büttner M, Trimpert J, Landthaler M. A pulmonologist's guide to perform and analyse cross-species

single lung cell transcriptomics. European Respiratory Review. 2022 Jul 27;31(165).

https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0056-2022 |

| 103 | Bauer C, Krueger M, Lamm WJ, Glenny RW, Beichel RR. lapdMouse: associating lung anatomy with local

particle deposition in mice. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2020 Feb 1;128(2):309-23.

https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00615.2019 |

| 104 | Raredon MS, Adams TS, Suhail Y, Schupp JC, Poli S, Neumark N, Leiby KL, Greaney AM, Yuan Y, Horien

C, Linderman G. Single-cell connectomic analysis of adult mammalian lungs. Science advances. 2019

Dec 4;5(12):eaaw3851.

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw3851 |

| 105 | Shang Y. Numerical modelling of inhaled particle transport and deposition in human and rat nasal

cavities (Doctoral dissertation, RMIT University).

|

| 106 | Xie K, Ren B, Peng Y, Wang F, Zhang X, Wang J, Shu Q. Hypoxia-Primed Human Umbilical Cord

Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Synovial Inflammation and Pulmonary Fibrosis via JNK/JAK-STAT3

Pathways in RA and RA-ILD. JAK-STAT3 Pathways in RA and RA-ILD.

|

| 107 | Aerts G, Willems L, Anthonissen R, De Jonghe B, Michiels J, Celen R, Verhaegen J, Vermaut A,

Geudens V, Hooft C, Kerckhof P. Micro-CT Based Approach to Quantitatively Evaluate Vascular Changes

in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2024 Apr

1;43(4):S114.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2024.02.227 |

| 108 | Neelakantan S, Xin Y, Gaver DP, Cereda M, Rizi R, Smith BJ, Avazmohammadi R. Computational lung

modelling in respiratory medicine. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2022 Jun

8;19(191):20220062.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2022.0062 |

| 109 | Sisodia Y, Shah K, Sayyed AA, Jain M, Ali SA, Gondaliya P, Kalia K, Tekade RK. Lung-on-chip

microdevices to foster pulmonary drug discovery. Biomaterials Science. 2023 Jan 31;11(3):777-90.

https://doi.org/10.1039/D2BM00951J |

| 110 | Fawaz A, Ferraresi A, Isidoro C. Systems biology in cancer diagnosis integrating omics

technologies and artificial intelligence to support physician decision making. Journal of

Personalized Medicine. 2023 Nov 10;13(11):1590.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13111590 |