Original Article - DOI:10.33594/000000835

Accepted 5 November 2025 - Published online

16 December 2025

Conifer Essential Oils Modulate Oxidative Stress and Erythrocyte Stability in Human Blood in Vitro

bDepartment of Physics, Institute of Exact and Technical Sciences, Pomeranian University in Słupsk, Słupsk, Poland,

cInstitute of Experimental Physics, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland,

dInstitute of Chemistry, Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce, Kielce, Poland,

eInstitute for Breath Research, University of Innsbruck, Dornbirn, Austria,

fDepartment of Tropical and Subtropical Plants, M. M. Hryshko National Botanic Garden, Kyiv, Ukraine

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Essential oils (EOs) derived from conifers of the Pinaceae family are complex bioactive mixtures known for their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. However, their impact on human redox homeostasis, particularly in blood, remains poorly understood. This study aimed to compare the redox-modulating and membrane-stabilising effects of essential oils from Scots pine (PEO), European spruce (SEO), and European silver fir (FEO) using an in vitro human blood model.Methods:

The chemical composition of each EO was characterised using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry (PTR-MS), and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Human blood samples were incubated with different EO concentrations, and oxidative stress biomarkers, antioxidant enzyme activities, and erythrocyte membrane stability were evaluated.Results:

All EOs exhibited terpene-rich profiles dominated by α-pinene, β-pinene, borneol, and bornyl acetate, with distinct species-specific differences. The oils displayed concentration-dependent biphasic redox effects. At moderate concentrations, PEO and SEO enhanced total antioxidant capacity and increased catalase and ceruloplasmin activities by 15–25% (p < 0.05). In contrast, higher doses—particularly of FEO—induced lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation by 40–60% (p < 0.05), indicating pro-oxidant behaviour. Erythrocyte haemolysis assays revealed that SEO exerted the strongest membrane-stabilising effect (haemolysis reduced by 18%), whereas FEO increased membrane fragility (haemolysis increased by 27%).Conclusion:

Pinaceae-derived essential oils exhibit dual antioxidant and pro-oxidant activity dependent on concentration and species. Among them, PEO showed the most balanced redox profile. These findings highlight both the therapeutic potential and the importance of controlled dosing when considering such oils for biomedical applications.Introduction

In recent decades, there has been growing interest in the scientific community in using natural bioactive compounds, particularly essential oils (EOs), as an alternative to conventional pharmaceuticals. This trend is largely motivated by concerns about the safety and side effects of synthetic therapeutic agents as well as the growing problem of drug resistance [1, 2]. Among plant-derived EOs, those extracted from coniferous trees of the Pinaceae family – particularly pine (Pinus sylvestris), spruce (Picea abies), and fir (Abies alba) – have attracted particular attention due to their diverse chemical compositions and a broad spectrum of biological activities [3-5]. Traditionally used in folk medicine to treat respiratory, inflammatory, and infectious conditions, these essential oils are now being extensively investigated for their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties, making them promising candidates for both therapeutic and preventive applications [3, 6]. Their multifunctional action, which combines direct antimicrobial activity with modulation of host defence systems, makes them particularly valuable. The antioxidant activity of EOs is a key property responsible for their ability to counteract oxidative stress [6, 7]

EOs are chemically complex mixtures of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), with terpenoids – particularly monoterpenes such as α-pinene, β-pinene, borneol, limonene, and bornyl acetate – representing the dominant constituents [8, 9]. Terpenes seem to be the largest and the most significant group of secondary metabolites in conifer trees. They function as both constitutive and inducible defence mechanisms protecting plants from invading pathogens and herbivores [10]. These compounds are widely recognised for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties [8, 11]. However, the composition of conifer-derived EOs can vary considerably depending on such factors as the plant species, its geographical origin, climatic conditions, seasonal changes, plant developmental stage, and the extraction techniques employed. Such variability strongly influences their pharmacological activity, highlighting the importance of comparative analyses to establish consistent therapeutic profiles and ensure reproducibility in biomedical applications [3, 12, 13]. Therefore, the standardisation and quality control of EOs are still essential prerequisites for their safe use in medicine.

The biological relevance of these oils is supported both by their ethnopharmacological applications and by modern pharmacological evidence. For example, Pinus extracts have long been employed in traditional Turkish medicine to relieve rheumatic pain and promote wound healing [14]. Recent investigations have elucidated the mechanisms underlying these effects demonstrating that specific terpenoids stimulate collagen synthesis, accelerate wound contraction, and reduce local inflammation [15, 16]. Beyond Pinus, essential oils from the genera Picea and Abies, which are particularly rich in bornyl acetate and α-pinene, have also exhibited notable antiviral and antimicrobial properties. For instance, Picea glehnii essential oil has been shown to exhibit potent antiviral activity against the hepatitis E virus, likely attributable to its terpenoid profile [17]. Similarly, Yu et al. (2025) reported that essential oils extracted from Pinus koraiensis needles possessed potent antibacterial activity, particularly against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [18]. In line with these findings, Liang et al. (2025) demonstrated that pine needle EOs enriched in volatile compounds, such as α-pinene, β-pinene, and germacrene D, display pronounced antibacterial and antioxidant activities, thereby expanding their therapeutic potential [19]. Collectively, these results underscore the promise of conifer-derived essential oils as a natural resource for addressing critical global health challenges, including antimicrobial resistance and viral epidemics [20, 21]. A key aspect of their therapeutic potential lies in their capacity to modulate oxidative stress, a pathophysiological state defined by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defence mechanisms in cells [22].

Human whole blood and isolated erythrocytes are a practical and mechanistically informative platform for the translation of research into redox modulation by phytochemicals. This is because they (i) recapitulate key cellular and plasma components relevant to systemic oxidative chemistry, (ii) permit the direct measurement of functionally meaningful endpoints, such as haemolysis, lipid peroxidation, antioxidant enzyme activities and total antioxidant capacity, and (iii) have been widely used to bridge the gap between simple chemical assays and complex in vivo responses. Whole blood preserves cell-plasma interactions and antioxidant buffering, which are absent from cell-free chemical tests and improve physiological relevance [23, 24]. Erythrocytes are particularly sensitive indicators of redox perturbation – their abundant haemoglobin, the high polyunsaturated lipid content of their membranes, and their well-characterised antioxidant systems make them a convenient and quantifiable indicator of oxidative damage and protection [25-27]. Methodologically, a variety of validated assays can be applied directly to human blood or erythrocyte preparations, allowing comparison across studies and with clinical biomarkers. These include hemolysis and osmotic fragility, lipid peroxidation, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), total antioxidant capacity (TAC), enzyme activity measurements, etc [28, 29].. Notably, ex vivo human blood studies have successfully demonstrated the protective or modulating effects of phytochemicals, including polyphenols and essential oils, on erythrocyte oxidative endpoints. This provides mechanistic support for subsequent in vivo or clinical investigations [30-32]. Using human blood models also offers ethical and practical advantages, such as direct access to human material, controlled exposure and reduced animal use, while permitting dose-response and time-course experiments that help interpret whether the in vitro antioxidant activity observed in chemical assays translates into biologically relevant effects [33-35]. However, we acknowledge the limitations of this approach, particularly the absence of first-pass metabolism, distribution, and complex organ crosstalk in isolated blood experiments. Therefore, we treat the human blood in vitro model as a mechanistic and translational intermediate that complements, but does not replace, in vivo or clinical studies [36, 37].

Blood components, particularly erythrocytes and plasma, are highly susceptible to oxidative damage, making them valuable systems for assessing the cytoprotective, pro-oxidant, and immunomodulatory effects of bioactive compounds [38-41]. Erythrocytes serve as reliable indicators of oxidative imbalance and membrane integrity due to their high polyunsaturated lipid content and limited repair mechanisms [42]. Meanwhile, plasma reflects systemic antioxidant status through its diverse pool of soluble antioxidants and proteins. Together, these two compartments provide a robust experimental framework for evaluating the safety, bioavailability, and therapeutic properties of essential oils [43]. This model is particularly relevant because it closely reflects the physiological environment of bioactive compounds circulating in the human body [41].

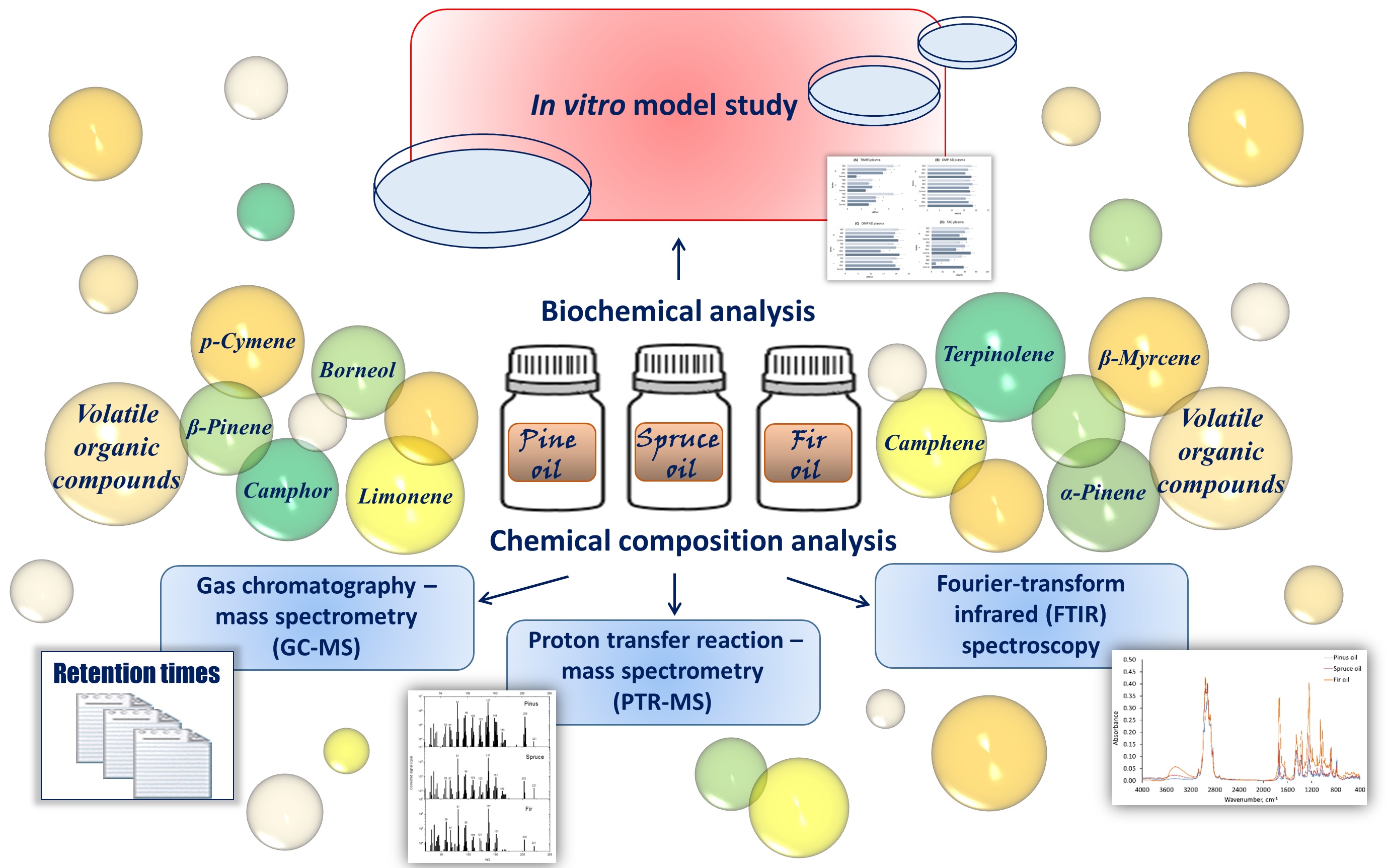

Against this background, the present study aims to perform a comparative analysis of essential oils derived from Pinus sylvestris, Picea abies, and Abies alba, with a particular focus on their chemical composition and biological activities in an in vitro human blood model. Advanced analytical techniques, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), proton transfer reaction-mass spectrometry (PTR-MS), and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), together with biochemical assays were employed to (i) characterise the VOC composition of the three coniferous EOs and (ii) evaluate their oxidant capacity by assessing markers of oxidative stress and haemolysis in human blood samples. By linking chemical profiles with functional biological outcomes, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of the dual role of Pinaceae-derived EOs in modulating oxidative stress and provides a scientific basis for their safe and effective use in the management of oxidative stress-related diseases.

Materials and Methods

Essential oils. The essential oils were provided by a Polish manufacturer (Naturalne Aromaty sp. z o.o., Bochnia, Poland). Three essential oils were investigated: Scots pine essential oil (PEO) derived from Pinus sylvestris, European spruce essential oil (SEO) derived from Picea abies, and European silver fir essential oil (FEO) derived from Abies alba. The manufacturers confirmed the natural origin of the samples documented by the quality certificates provided with each batch and declared that the oils did not contain additives or solvents. The samples were stored in sealed amber glass vials at 4°C in the dark but were allowed to adjust to room temperature prior to analysis. These conditions minimised the risk of volatile compound degradation and ensured sample stability. The precise geographical origin of the samples could not be established, as detailed sourcing information was not consistently available.

Physical and chemical analysis of the essential oil composition

Chromatographic analysis. The volatile compounds emitted by the EOs under study were

pre-concentrated using headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME). Shortly before analysis,

approximately 1 μL of oil was transferred into a 20 mL headspace vial (Gerstel, Germany). The vial was

purged with high-purity air to remove potential ambient contaminants and then sealed with 1.3 mm

butyl/PTFE septa (Macherey-Nagel, Germany).

Prior to extraction, the vial was incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. HS-SPME was performed using an

automated MPS2 autosampler (Gerstel, Germany), which inserted an SPME fibre coated with 75 µm CAR/PDMS

(Supelco, Canada) into the vial and exposed it to the headspace for 10 minutes at 37°C. After extraction,

the fibre was introduced into the gas chromatograph (GC) inlet, where the analytes were thermally desorbed

in the splitless mode at 290°C for one minute.

Analysis was performed using a gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) system (Agilent 7890A/5975C,

Agilent Technologies, USA). The GC inlet was equipped with an inert SPME liner (0.75 mm internal diameter,

Supelco, Canada) and was initially operated in the splitless mode, followed by the split mode with a 1:50

split ratio. VOCs were separated on an Rxi-624Sil MS column (30 m × 0.32 mm, 1.8 µm film thickness;

Restek, USA) with a constant helium flow of 1.5 mL min⁻¹.

The GC oven was programmed as follows: an initial temperature of 40°C (held for 10 minutes), increased at

5°C per minute to 150°C (held for 5 minutes), followed by a ramp of 10°C per minute to 280°C, with a final

hold at 280°C for 10 minutes. The mass spectrometer operated in the SCAN mode with a mass range of m/z

20-250. The quadrupole, ion source, and transfer line temperatures were set to 150°C, 230°C, and 280°C,

respectively.

Compound identification was based on mass spectral matching using the NIST library. Where possible,

identities were confirmed by comparing the retention times of the target compounds with those obtained

from authentic standard mixtures.

Proton transfer reaction – mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) analysis. The content of VOCs in the

essential oils was analysed using a high-sensitivity PTR-MS (IONICON Analytik GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria)

operating in the 1-512 amu mass range. This technique uses soft ionisation, which involves transferring a

proton from a hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) to the target molecule. The reaction can be represented by the

following equation:

$${{ \text{H}_2\text{O}^+ + \text{M} \longrightarrow \text{H}^+ \text{M} + \text{H}_2 \text{O}

\hspace{50px} \text{(1)}}}$$

Unlike traditional ionisation methods (e.g. electron impact), the PTR-MS induces significantly less

fragmentation of VOC molecules, thereby facilitating the interpretation of mass spectra, particularly in

the case of complex mixtures. This technique is widely applied in air quality monitoring, in the analysis

of VOC emissions from food products (including fruits [44, 45], and in medical and physiological studies,

such as human breath analysis [46]. For comprehensive overview, see relevant reviews [47, 48].

To prevent detector saturation caused by the high concentration of certain VOCs in the samples, all oil

headspaces were diluted prior to analysis. The gas phase above the oils in their original packaging was

sampled using 10-mL syringes. The collected gas was subsequently transferred into 200-ml plastic vessels

wrapped in aluminium foil. A capillary tube was then inserted through a small hole in the foil, enabling

introduction of the gaseous sample into the PTR-MS drift chamber.

To prevent the condensation of volatile components, the capillary and the drift chamber were both

maintained at a temperature of 60°C. To minimise contamination from previous measurements, each oil sample

was analysed one day after the previous one. During the intervals between measurements, the system was

flushed with purified air.

Background measurements were conducted prior to each sample analysis to confirm the absence of VOCs

originating from previous runs. Subsequently, mass spectra were recorded with six scans per sample within

a mass range from 21 to 300 Da. All measurements were performed in standardised conditions: specifically,

a drift chamber pressure of 2.2 mbar and a drift voltage of 600 V were used.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

(FTIR) analysis was also done to identify some components in the studied oils. The measurements were

performed on a Nicolet iS50 FTIR Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Infrared

absorption spectra were obtained using the KBr pellet method. A drop of oil was placed on the KBr pellet

to form a thin film, and then an IR absorption spectrum was measured. All measurements were performed at

room temperature (about 21°C). Absorption spectra in the infrared range contain information about the

vibrational frequencies of the chemical bonds of functional groups, such as C-C, C-H, C-O, O-H, N-H, etc.

Therefore, IR spectra can be used to identify some organic compounds. For this reason, FTIR spectroscopy

is widely applied in biological and chemical studies [49, 50].

Multi-component decomposition (up to 4 components) of the measured spectra was performed using OMNIC

Specta Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The chemical structures were visualised using

GaussView 5.0.9 software.

Human blood samples. Peripheral blood (approximately 60 ml) was obtained via venipuncture from

eight healthy volunteers (four males and five females aged 28-53 years). The study protocol was approved

by the Research Ethics Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Gdańsk, Poland (KB-31/18). Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment.

Human erythrocytes were isolated from citrated blood by centrifugation at 3, 000 rpm (~1, 500×g) for 10

minutes at 4°C. The plasma and buffy coat were carefully removed and the erythrocytes were washed three

times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 4 mM, pH 7.4) until the supernatant became clear. The final

erythrocyte pellet was resuspended in the same buffer to achieve a suspension with the desired

haematocrit. The cells were stored at 4 °C and used within 6 hours of preparation to ensure viability. To

preserve inter-individual variability, blood from different donors was analysed separately. Therefore,

each donor sample represented one biological replicate (n = 8). Each biochemical assay was performed in

triplicate for each donor sample.

Experimental design. For the experimental assays, human erythrocytes and plasma samples were

incubated with the essential oils at the following ratios: 1:9, 1:99, and 1:999 (v/v). All incubations

were performed in a final assay volume of 2.5 ml. Depending on the density of the individual oils, the

ratios 1:9, 1:99 and 1:999 corresponded to final EO concentrations of 100 µL/mL (88-94 mg/mL), 10 µL/mL

(8.8-9.4 mg/mL) and 1 µL/mL (0.88-0.94 mg/mL), respectively. As EOs are hydrophobic, the oils were first

dissolved in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to create stock solutions, which were then diluted in

phosphate buffer (4 mM, pH 7.4) to achieve the desired final concentrations. The final DMSO content in all

samples, including vehicle controls, did not exceed 0.01% for the 1:9 ratio, 0.001% for the 1:99 ratio,

and 0.0001% for the 1:999 ratio. This was confirmed not to affect erythrocyte stability. Independent

control experiments demonstrated that 0.01% DMSO had no statistically significant effect on erythrocyte

stability, lipid peroxidation (TBARS), protein carbonylation, antioxidant enzyme activity or total

antioxidant capacity (P > 0.05 vs. untreated controls; see Supplementary Table S1 for data).

For the 2.5 ml incubation volume, the mixtures were prepared as follows: for the 1:9 ratio, 0.25 mL of the

oil solution was combined with 2.25 mL of the erythrocyte suspension or plasma; for the 1:99 ratio, 25 µL

of the oil solution was mixed with 2.475 mL of the sample; and for the 1:999 ratio, 2.5 µL of the oil

solution was added to 2.4975 mL of the sample. For the 1:999 ratio, the stock solution was

pre-diluted 1:10 to improve pipetting accuracy.

The mixtures were gently agitated in a Thermomixer at 37°C and 75 rpm for 60 minutes to ensure homogeneity

and prevent sedimentation. The vehicle controls consisted of erythrocytes or plasma incubated with

phosphate buffer containing the final desired concentration of DMSO. Following the incubation, erythrocyte

and plasma samples were collected and processed for subsequent biochemical analysis.

Reagents. All chemicals were of analytical grade. The main reagents used in biochemical assays were

purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany): 2-thiobarbituric acid, trichloroacetic acid, 2,

4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, ABTS, potassium persulfate, hydrogen peroxide, Trolox, p-phenylenediamine, and

sodium chloride. Other chemicals and solvents were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, USA)

and POCH (Gliwice, Poland).

Lipid peroxidation (TBARS assay). Lipid peroxidation was assessed by quantifying 2-thiobarbituric

acid-reactive substances (TBARS), primarily malondialdehyde (MDA), using Buege and Aust's method (1978)

[51] with slight modifications. In brief, 0.1 ml of the sample was mixed with 2.0 ml of distilled water

and 2.0 ml of TBA reagent consisting of 15% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 0.375% 2-thiobarbituric acid

(TBA), and 0.25 N hydrochloric acid (HCl). The samples were then incubated in a boiling water bath at 95°C

for 15 minutes, cooled on ice, and centrifuged at 3, 000 rpm for 10 minutes. The absorbance of the

resulting supernatant was measured at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer. The MDA concentration, which

indicates the extent of lipid peroxidation, was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 1.56 ×

105 M⁻¹·cm⁻¹.

Protein oxidation (DNPH assay for carbonyl groups). The degree of protein oxidation was determined

by measuring the carbonyl content through a reaction with 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) according to

the method described by Levine et al. (1990) [52] with slight modifications. In brief, 0.1 ml of the

sample was mixed with 0.5 ml of 10 mM DNPH in 2 N hydrochloric acid (HCl). The samples were then incubated

at room temperature for one hour with intermittent vortexing. After the incubation, the proteins were

precipitated using 20% TCA and the mixture was centrifuged at 10, 000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting

pellet was washed three times with a 1:1 (v/v) ethanol:ethyl acetate mixture to remove excess DNPH and was

then dissolved in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. The absorbance of the resulting hydrazone derivatives was

measured at 370 nm and 430 nm using a spectrophotometer. The carbonyl content was then calculated using an

extinction coefficient of 22, 000 M⁻¹·cm⁻¹ and expressed in nmol/mL.

Total Antioxidant Capacity (ABTS Assay). Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was measured using the

ABTS (2, 2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)) radical cation decolourisation assay

according to the method described by Miller et al. (1993) [53]. The ABTS radical cation (ABTS⁺) was

generated by incubating a 7 mM ABTS solution with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate for 12-16 hours in the dark

at room temperature. The resulting ABTS⁺ solution was diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to

obtain an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Next, 20 µL of the sample was mixed with 980 µL of the

ABTS⁺ solution, incubated for 6 minutes at room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm.

The antioxidant capacity was calculated based on a Trolox standard curve and expressed as µmol Trolox

equivalents per mL.

Catalase activity. Catalase (CAT) activity was determined by measuring the decomposition of

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) according to the method described by Claiborne (1985) [54].

Briefly, 50 µL of the sample was added to 2.95 mL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) containing 15 mM

H₂O₂. The decrease in absorbance was recorded at 240 nm for 1 minute using a spectrophotometer. One unit

of catalase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to decompose 1 µmol of

H2O2 per minute per mL.

Ceruloplasmin concentration. The concentration of ceruloplasmin in serum was determined with a

colourimetric method based on its oxidase activity towards p-phenylenediamine (PPD) as a substrate. The

rate of PPD oxidation to a coloured product was measured spectrophotometrically at 546 nm. The intensity

of the colour developed was directly proportional to the ceruloplasmin concentration in the sample.

Ceruloplasmin activity was expressed in mg/mL using a calibration curve constructed from known

ceruloplasmin concentrations according to the method described by Ravin (1961) [55].

Spontaneous haemolysis. The degree of spontaneous haemolysis was assessed by measuring the release

of haemoglobin from erythrocytes into plasma in in vitro conditions, without the use of haemolytic

agents. Blood samples were centrifuged to separate the plasma, and the erythrocytes were incubated in

physiological conditions at 37°C for 24 hours. Following the incubation, the supernatant was collected by

centrifugation, and its absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. Haemolysis was expressed

as a percentage of spontaneous haemolysis relative to the total haemolysis induced by erythrocyte lysis in

distilled water according to the method described by Kamyshnikov (2004) [56].

Osmotic fragility test. The osmotic fragility of erythrocytes was evaluated as in Mariańska et al.

(2003) with minor modifications [57]. In brief, a series of sodium chloride (NaCl) solutions ranging from

0.00% to 0.90% (w/v) were prepared by diluting isotonic saline with distilled water. An aliquot of blood

(50 µL) was added to 5.0 mL of each NaCl solution, mixed thoroughly, and incubated at room temperature for

30 minutes. Distilled water served as the control for 100% haemolysis.

Following the incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 1, 500 g for five minutes to sediment intact

erythrocytes. The resulting supernatant was carefully collected and the absorbance measured

spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. The percentage of haemolysis was calculated relative to the controls.

Haemolysis curves were plotted as a function of NaCl concentration to determine the onset and completion

of haemolysis.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 13.3 software (TIBCO

Software Inc., Palo Alto, USA). Normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test, and homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene's test [58, 59]. Data that did not meet the

assumptions of parametric tests were logarithmically transformed prior to further analysis.

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for n = 8 independent biological

replicates. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to evaluate differences between groups, with

an F-test considered significant at P < 0.05. When ANOVA revealed significant effects, Tukey's post hoc

test was used to identify specific intergroup differences. Additionally, two-tailed Student's t-tests (α =

0.05) were performed to compare control samples with each EO treatment at different concentrations.

Variability and the effect size were assessed using coefficients of variation (CV%) and Cohen's d,

providing measures of reproducibility and biological relevance, respectively. Regression analyses were

performed to examine concentration-dependent effects for each essential oil on oxidative stress markers

and erythrocyte haemolysis. This approach allowed precise detection of biphasic or dose-dependent

responses in both plasma and erythrocytes.

For osmotic haemolysis studies, the effects of each essential oil at three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and

1:999) across a range of NaCl concentrations were evaluated using ANOVA, followed by a Tukey's post hoc

test. This analysis enabled the assessment of the modulation of erythrocyte membrane stability in relation

to both the oil concentration and the osmotic condition.

Results

This study investigated the effects of three EOs from the Pinaceae family: Pinus sylvestris (Scots pine), Picea abies (European spruce), and Abies alba (European silver fir) on oxidative stress markers, antioxidant capacity, enzymatic activity, and haemolytic potential in human blood. As blood plasma and erythrocytes possess distinct antioxidant systems with different mechanisms and efficiencies, separate experiments were conducted on plasma and erythrocyte suspensions to assess the effects of EOs applied at various concentrations. Each EO was tested at three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999, v/v). The vehicle controls consisted of erythrocytes or plasma incubated with phosphate buffer. The results revealed distinct concentration-dependent biological activities for each EO, with fir essential oil exhibiting the most pronounced effects.

Fig. 1: Study design.

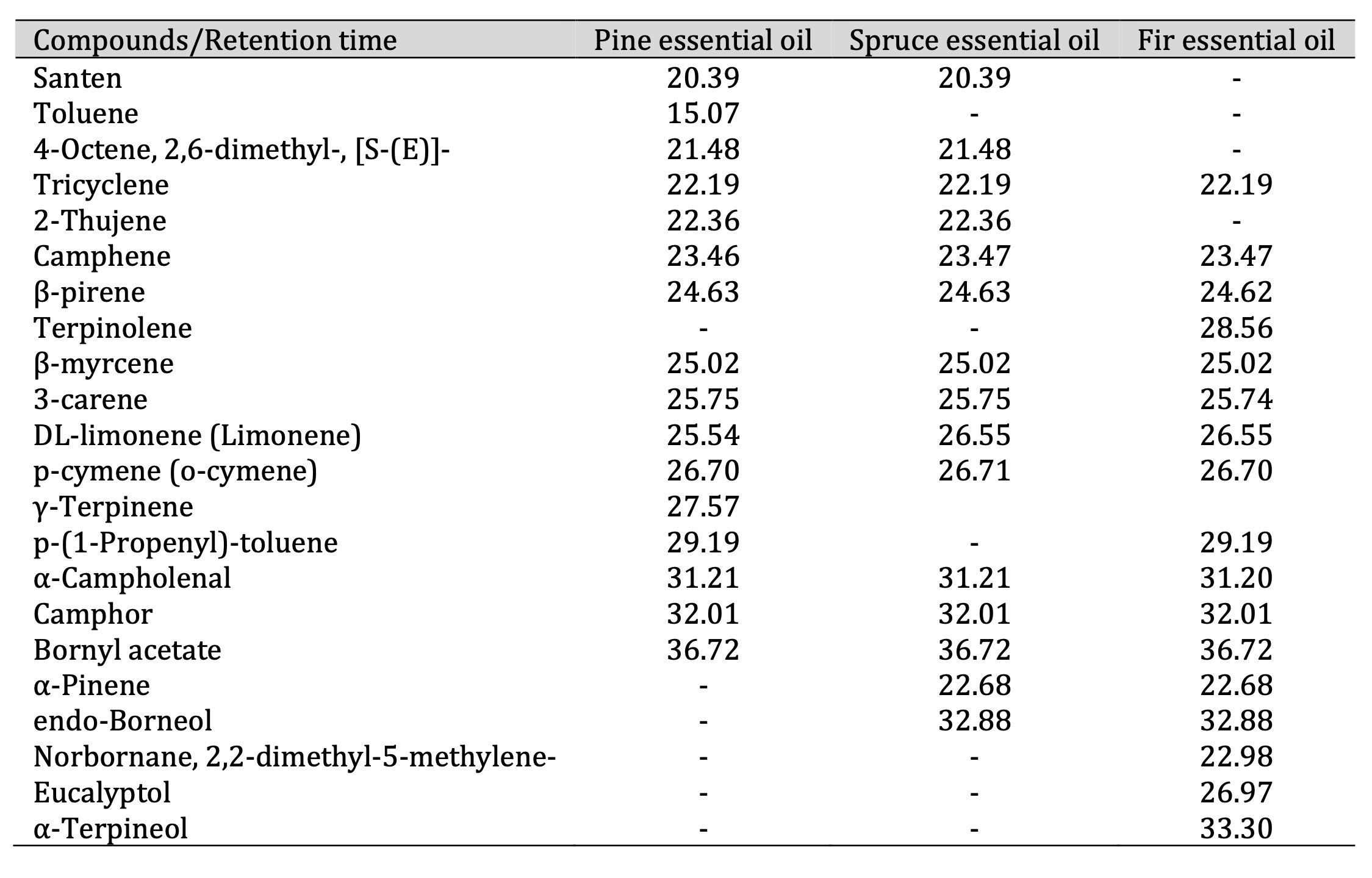

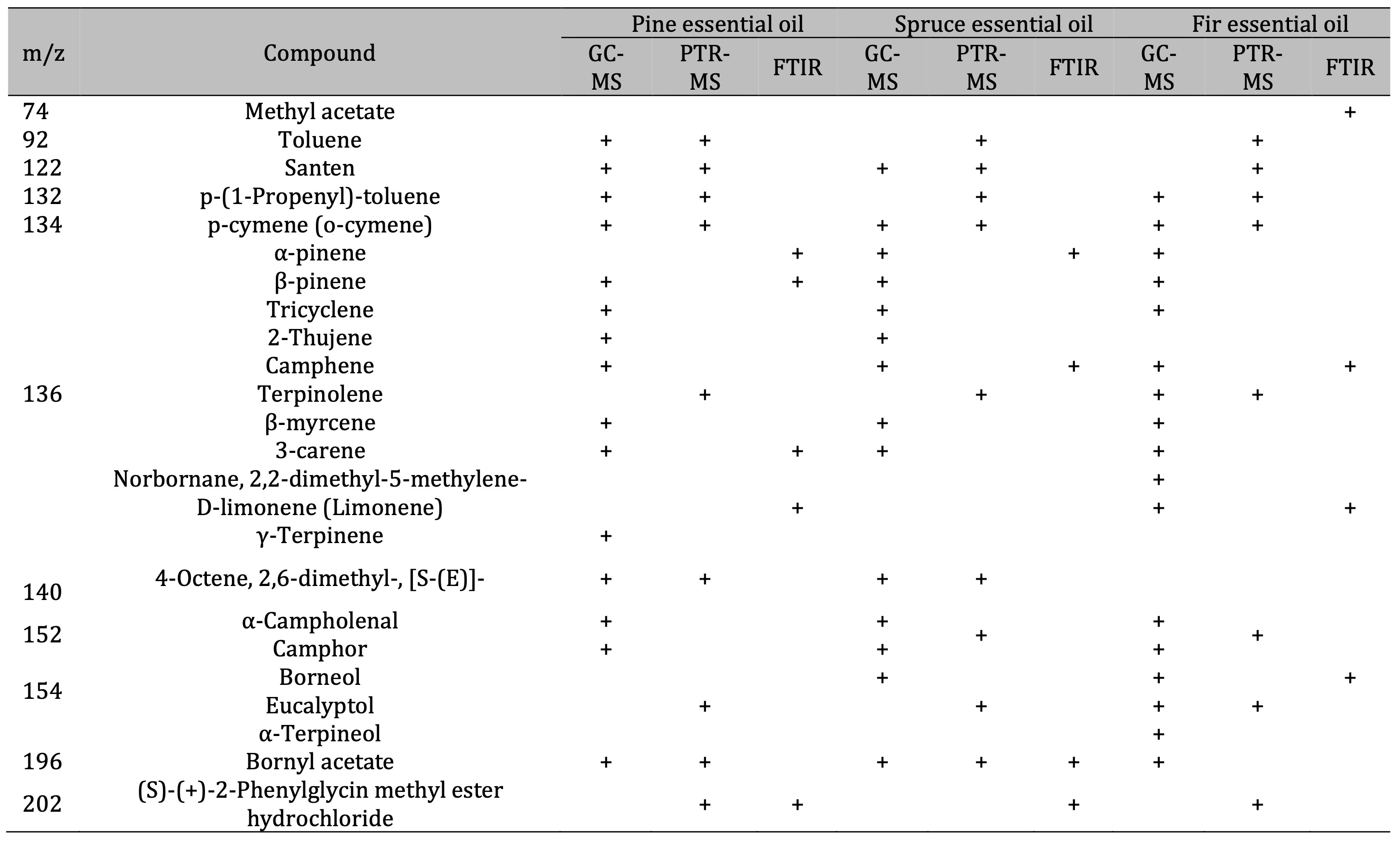

GC-MS and PTR-MS analysis. Table 1 lists the VOCs identified using GC-MS. The dominant class

amongst the identified VOCs were monoterpenes, including santene, α-pinene, β-pinene, tricyclene,

2-thujene, camphene, campholenal, and borneol. In addition, the borneol ester bornyl acetate was

identified. The identification of individual compounds was based on a comparison of their mass spectra

with those in the NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library as well as a comparison of their retention indices

with data from the literature.

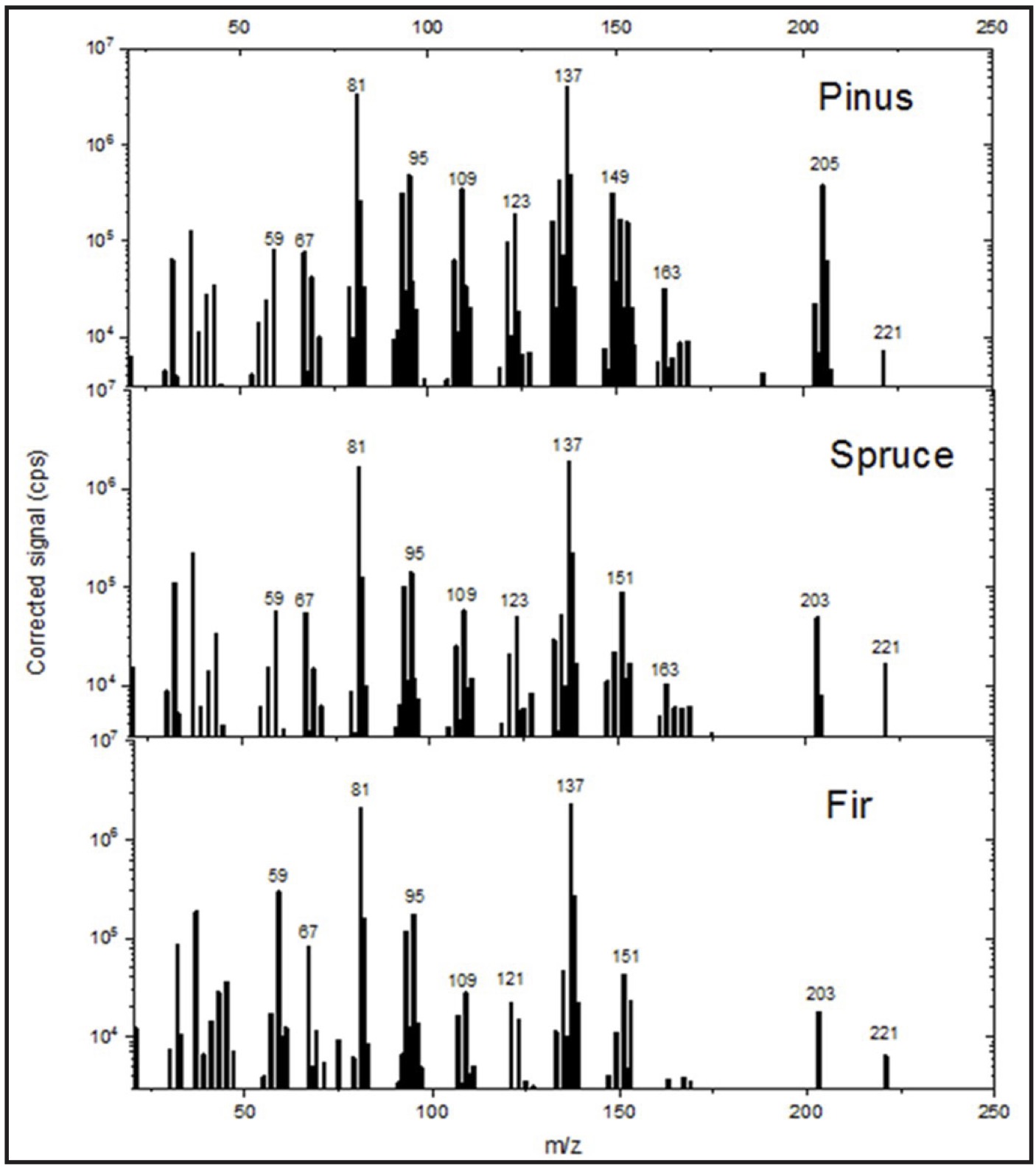

These results are consistent with the PTR-MS data, as shown in Fig. 2, which also indicate the m/z values

corresponding to the major peaks originating from protonated VOCs in the spectra.

Table 1: Retention times (in minutes) of pine, spruce, and fir essential oil compounds

Fig. 2: Mass spectra (PTR-MS) of pine, spruce, and fir essential oil samples.

These values were primarily 81 (terpene fragment ions), 137 (a common m/z value for monoterpenes), 123

(santenes), 95 (an unidentified compound, most likely C₇H₁₀ or C₆H₆O), 109 (C8H12 or

C7H8O), 149 (probably anethole, C₁₀H₁₂O), 151 (probably piperonal, C₈H₆O₃), 203

(possibly C₁₄H₁₈O), 205 (sesquiterpenes, such as bisabolenes, amorphenes, and cadinenes), and 221

(possibly C₁₅H₂₄O).

The mass spectrum lacks the m/z = 197 peak, which corresponds to protonated bornyl acetate. However, as

demonstrated by Kim et al. (2009) [60], bornyl acetate undergoes fragmentation and is recorded at masses

of 137 and 81.

Therefore, the GC-MS analysis confirmed the presence of high concentrations of the following monoterpenes

in the EOs studied: α-pinene, β-pinene, borneol, and camphene. The compound identification was validated

using the NIST library and by comparing the results with those of authentic analytical standards and

calculated Kovats retention indices (RI). These results are consistent with the PTR-MS data and highlight

a complex species-specific VOC profile, thereby supporting the potential biological and therapeutic

activities of the EOs.

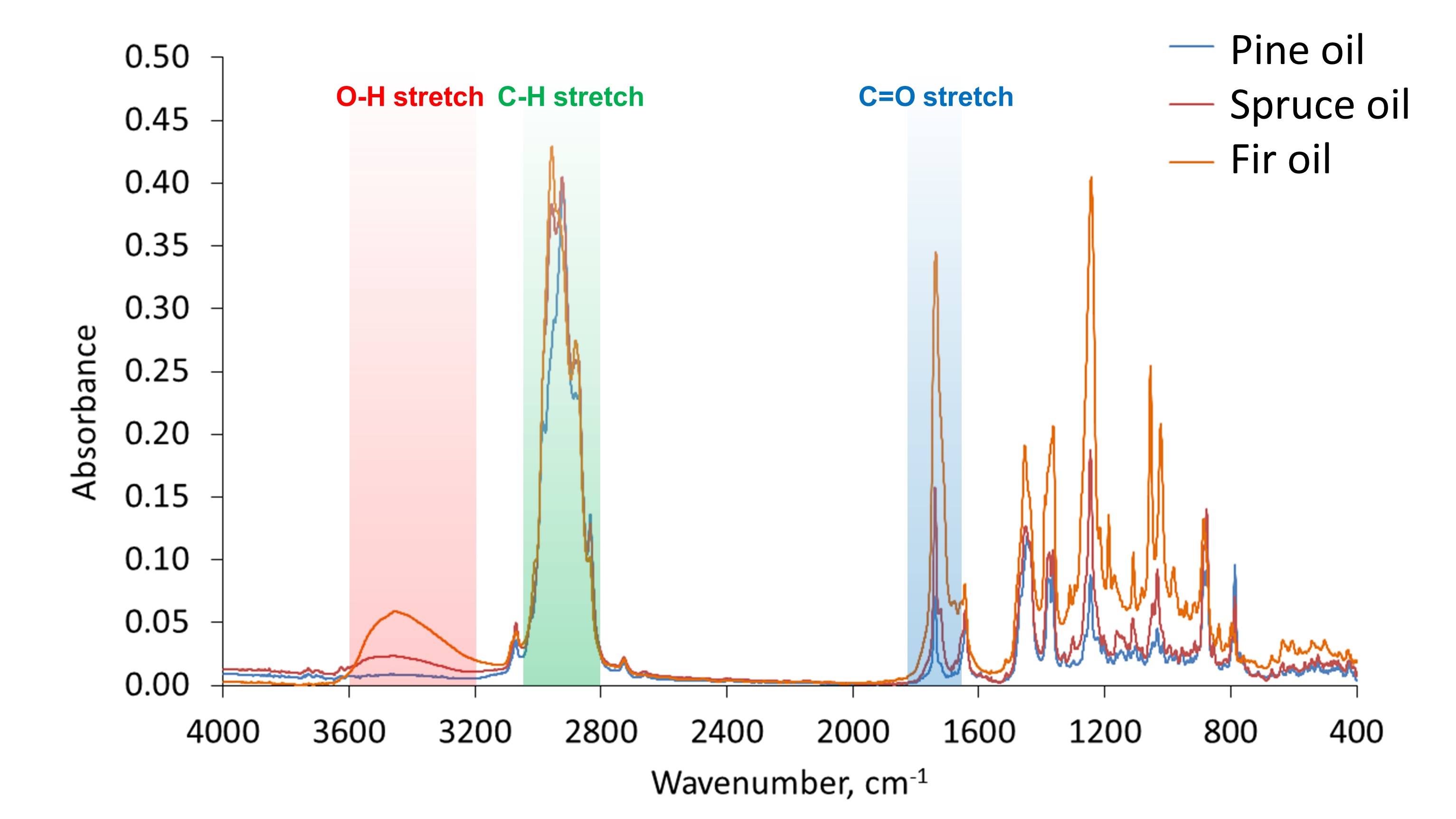

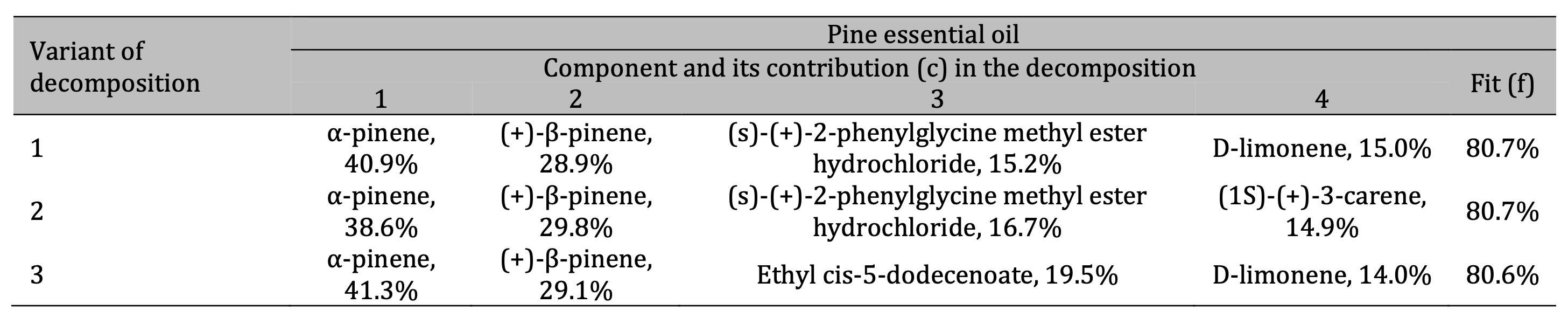

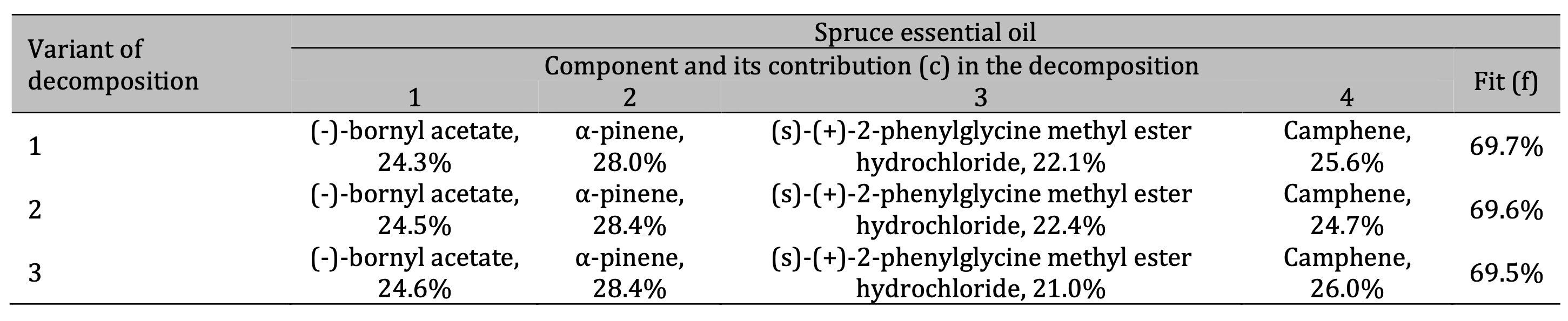

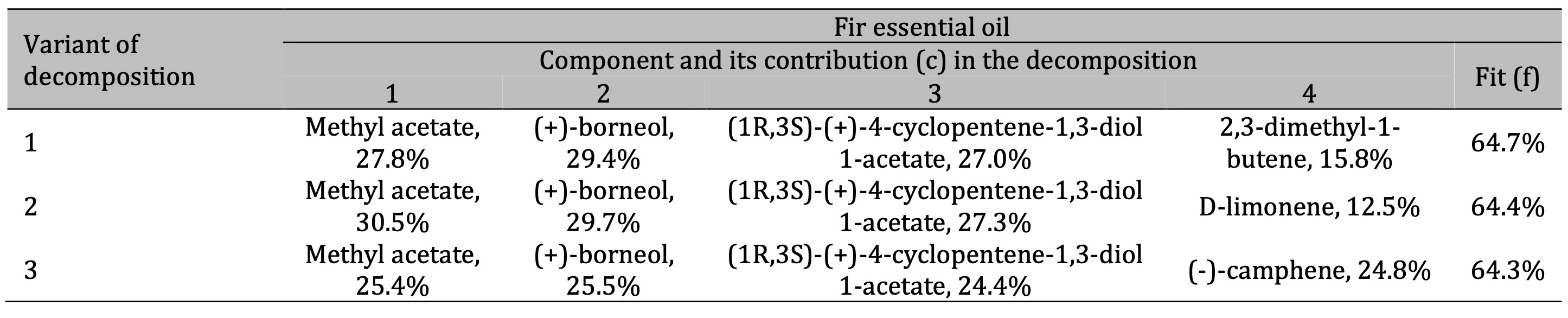

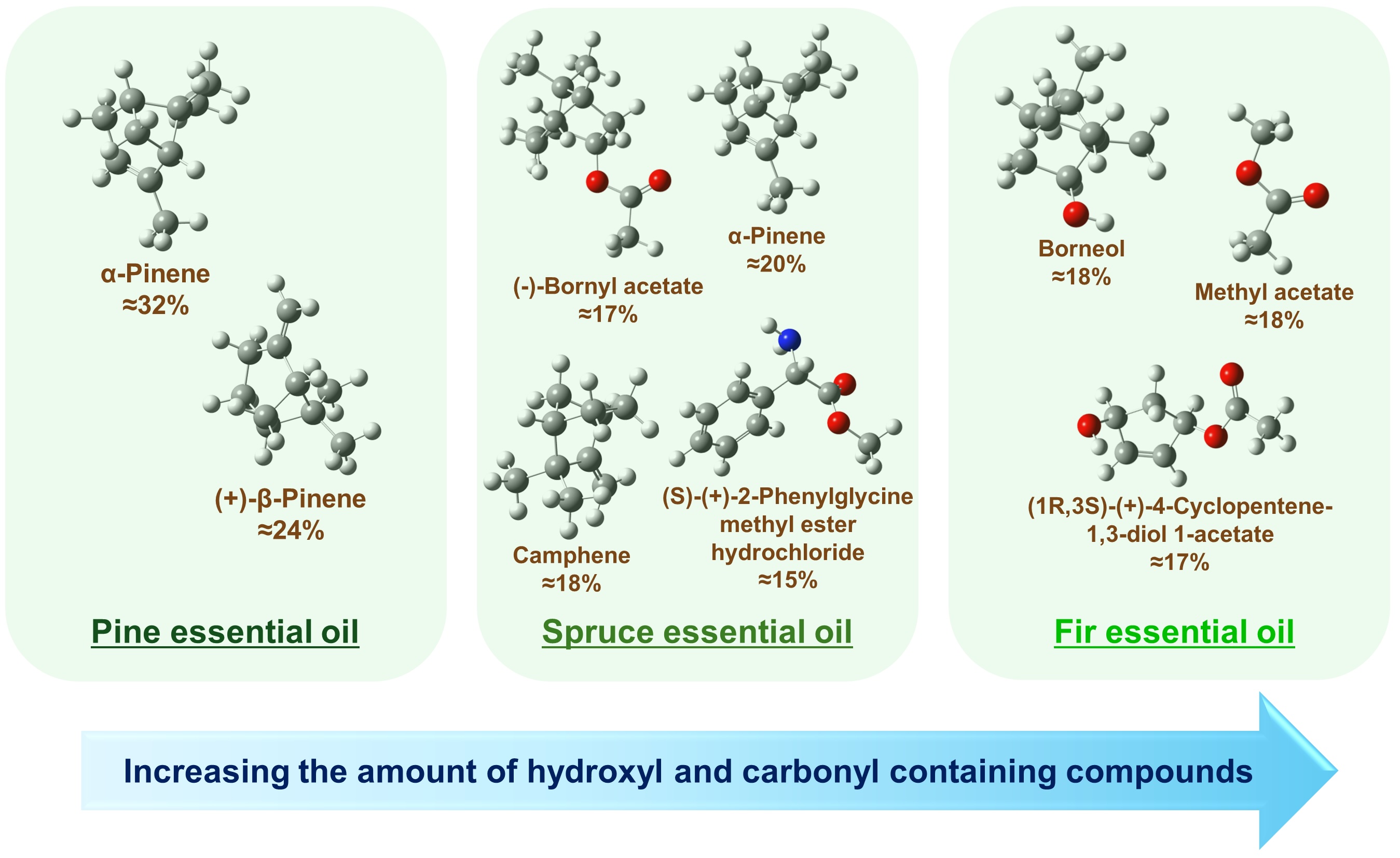

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis. The infrared (IR) absorption spectra of the essential oils derived from pine, spruce, and fir are presented in Fig. 3. The results of the four-component decompositions of the spectra are summarised in Tables 2, 3, and 4 for pine, spruce, and fir essential oils, respectively. It should be noted that the highest decomposition fit was achieved for the pine oil sample, i.e. about 80%, while it was about 70% and 64% in the case of the spruce and fir oil samples, respectively. Therefore, to roughly estimate the percentage of detected compounds in the samples, the following equation was applied: $${{p(\%) = \frac{c(\%) \times f(\%)}{100 \%}}} \hspace{50px} \text{(2)}$$ where p is the estimated percentage of a compound in the sample, c is the contribution of the compound in the spectral decomposition (in %), and f is the decomposition fit (in %). Parameters c and f are given in Tables 2-4.

Fig. 3: IR absorption spectra of pine, spruce, and fir essential oil samples. Bands corresponding to different stretching vibrations are highlighted in red, green, and blue.

Table 2: Results of the three best variants of the four-component decomposition of IR absorption spectra of pine essential oils

Table 3: Results of the three best variants of the four-component decomposition of IR absorption spectra of spruce essential oils. All decomposition variants show the same components with different contents

Table 4: Results of the three best variants of the four-component decomposition of IR absorption spectra of fir essential oils

For the pine essential oil (Table 2), the FTIR analysis revealed that the two main components are α-pinene

and (+)-β-pinene, which together account for approximately 70% of the IR spectral decomposition. According

to Eq. (2), it gives the percentage of these two compounds of about 55% in the sample. These two pinenes

represent a significant portion of the chemical composition of the oil. Furthermore, the analysis

identified (S)-(+)-2-phenylglycine methyl ester hydrochloride, 3-carene, and d-limonene as notable

components in the pine oil.

In the case of the spruce essential oil (Table 3), the main components were identified as (-)-bornyl

acetate with about 24% contribution in the spectral decomposition (giving approximately 17% of the total

content), α-pinene with about 28% contribution (giving approximately 20% of its content in the sample),

and camphene with a percentage of about 18% estimated according to Eq. (2) based on data shown in

Table 3. The spectral decomposition also revealed the presence of (s)-(+)-2-phenylglycine methyl

ester hydrochloride in the spruce oil.

Finally, the FTIR analysis of the fir essential oil (Table 4) showed the presence of methyl acetate,

(+)-borneol, and possibly significant amounts of 4-cyclopentene-1, 3-diol 1-acetate, d-limonene, and

camphene. The organic compounds identified from the FTIR spectra are listed in Table 5, alongside those

detected using alternative analytical techniques.

Table 5: Comparison of the results of VOC identification in essential oils using GC-MS, PTR-MS, and FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectroscopy analysis of the essential oils confirmed that the dominant components are

monoterpenes, with α-pinene and β-pinene comprising approximately 55% of the pine oil. The spruce oil was

found to be predominantly composed of α-pinene, (-)-bornyl acetate, and camphene, while the fir oil was

found to contain methyl acetate and (+)-borneol. These findings underscore the chemical specificity of

each oil type and corroborate the results obtained using complementary analytical methods.

Based on the infrared spectra decomposition analysis, the main detected components (with a content of at

least 15% estimated according to Eq. (2)) are presented in Fig. 4 for each type of essential oil. To gain

more insights into the chemical properties of the studied samples, the absorption bands in the infrared

spectra were analysed in detail. The intensive band at about 2900 cm-1, observed in the three

samples (highlighted in green in Fig. 3), corresponds to C-H stretch occurring in various organic

compounds of essential oils. There are multiple maxima at this absorption band indicating symmetric and

asymmetric stretching vibrations of aliphatic CH2 and CH3 groups, as typically

observed in oils [50]. The broad band at 3200-3600 cm-1 was intensive in the fir oil and less

intensive in the spruce oil, while it did not occur in the case of the pine oil sample (highlighted in red

in Fig. 3). This band corresponds to O-H stretching vibrations. It allows concluding that the investigated

pine oil sample almost does not consist of hydroxyl-containing compounds. The peak at about

1700 cm-1 corresponds to the absorption associated with the carbonyl group (highlighted in

blue in Fig. 3). It is typically assigned to C=O double bond stretching vibrations. The highest intensive

peak at about 1700 cm-1 was observed for the fir oil sample; it was less intensive for the

spruce oil, and the least intensive band was observed for the pine oil sample. Therefore, it could be

concluded that oxygen-containing compounds were found in the highest amount in the fir oil among the three

studied samples (as shown in Fig. 4), and the spruce oil sample contained lower amounts of such molecules,

while the pine oil was characterised by the lowest content of compounds containing oxygen species, such as

hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. It should be noted that the difference between the investigated essential

oils in the absorption region assigned to hydroxyl stretching vibrations (3200-3600 cm-1) can

be also explained by the presence of water impurities in the samples of the spruce and fir oils. This is

understandable given that the research deals with essential oils commercially available for general use.

However, this explanation cannot be extended to the observed spectral differences at the region of

carbonyl stretching vibrations at about 1700 cm-1 in the spectra. These differences can be

explained only by variations in the amount of carbonyl containing compounds among the essential oil

samples, as concluded before.

Fig. 4: The most abundant compounds with their percentages in pine, spruce, and fir essential oils obtained from the FTIR spectroscopic analysis. Approximate percentages were estimated using Eq. (2) by taking the mean values across all decomposition variants given in Tables 2-4. In the chemical structures, the white balls denote hydrogen, the grey balls denote carbon, the red balls denote oxygen, and the blue ball denotes nitrogen.

Other absorption peaks at lower wavenumbers in the IR spectra (not highlighted in Fig. 3) refer to other (than stretching) deformation and bending vibrations of CH bonds and the fingerprint region.

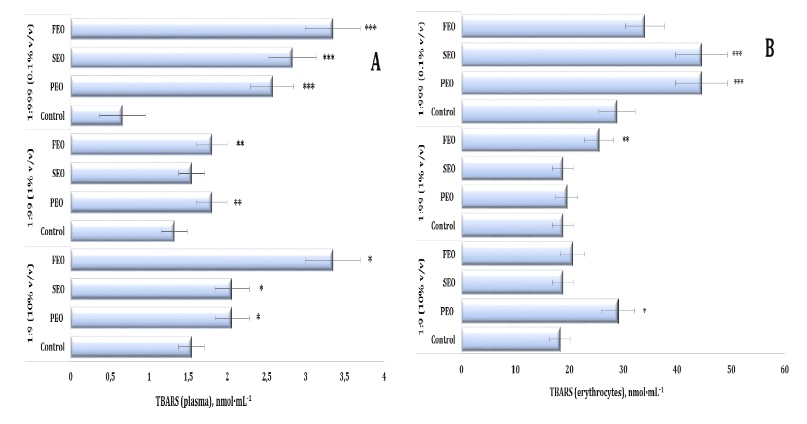

Oxidative stress markers. Lipid peroxidation, assessed by TBARS levels in human plasma and

erythrocytes, was significantly affected by the three EOs (PEO, SEO, and FEO) (F11, 72 = 68.07,

P < 0.001). As illustrated in Fig. 5A, FEO induced the strongest pro-oxidative effect at a dilution of

1:9, producing a twofold increase in plasma TBARS levels, compared with the control group (p < 0.01).

Significant but less pronounced increases were also observed for SEO and PEO at this dilution (p <

0.05). In the erythrocytes, a clear dose-dependent pattern emerged, with TBARS levels rising progressively

across the dilutions (1:9 < 1:99 < 1:999). Notably, even at 1:999, both SEO and PEO maintained

significantly elevated TBARS levels relative to the control, indicating persistent oxidative stress.

Significant and persistent changes in the TBARS levels in the erythrocytes were observed throughout the

experiment (F11, 72 = 72.16, P < 0.001). Enhanced lipid peroxidation was recorded after the

PEO treatment at the 1:9 dilution and after the FEO treatment at the 1:99 dilution as well as after the

exposure to both PEO and SEO at the 1:999 dilution, compared to the control group. The highest TBARS

values were recorded at the 1:999 dilution, indicating the strongest oxidative response (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5: TBARS level in human blood plasma (A) and erythrocytes (B) measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of essential oils from pine (PEO), spruce (SEO), and fir (FEO) in an in vitro study.* Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:9, compared to the control;** Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:99, compared to the control;*** Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:999, compared to the control.

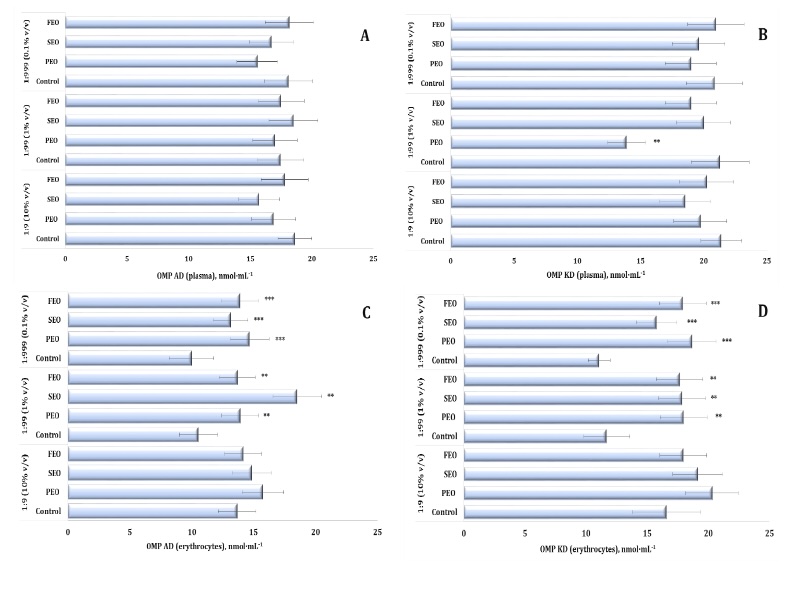

Oxidatively modified proteins (OMPs) were assessed by measuring aldehydic (OMP AD) and ketonic (OMP KD)

derivatives to further characterise the oxidative effects of the conifer-derived EOs. In the plasma, no

statistically significant changes were detected in the OMP AD levels, whereas the OMP KD levels were

significantly affected (F11, 72 = 2.19, P = 0.029), with a marked decrease observed for PEO

at

the 1:99 dilution (Fig. 5A and 5B). In the erythrocytes, however, both OMP AD and OMP KD consistently

increased after the treatment with the three oils, particularly at the 1:99 and 1:999 dilutions. At

these

concentrations, PEO, FEO, and SEO significantly elevated OMP AD levels (F11, 72 = 8.96, p

<

0.001) and OMP KD (F11, 72 = 14.54, p < 0.001), compared with both the control and 1:9

dilution treatments (Fig. 6C and D).

Notably, even at the most diluted concentration (1:999), the three EOs maintained elevated levels of

protein oxidation markers in the erythrocytes, highlighting their persistent pro-oxidative potential at

the cellular membrane level. These findings emphasise the dual oxidative potential of conifer-derived

EOs in human blood in vitro, with FEO demonstrating the strongest and most consistent

pro-oxidative effects across the biomarkers and dilutions.

Fig. 6: Level of aldehydic and ketonic derivatives of oxidatively modified proteins in human blood plasma (A, B) and erythrocytes (C, D) measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of essential oils from pine (PEO), spruce (SEO), and fir (FEO) in an in vitro study.** Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:99, compared to the control;*** Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:999, compared to the control.

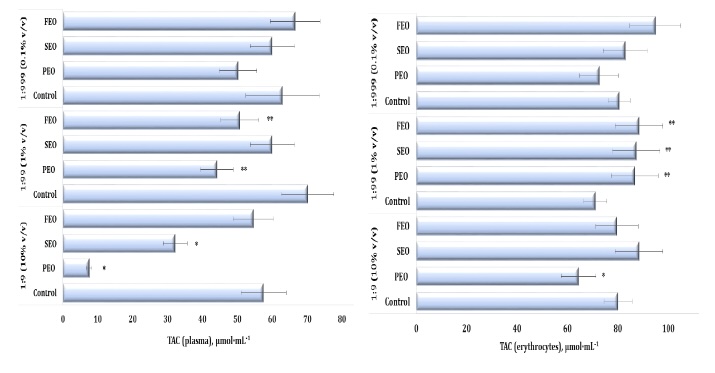

Our study demonstrated that the exposure to the three conifer-derived EOs induced oxidative stress in the human plasma, as reflected by significant alterations in total antioxidant capacity (TAC) (F11, 72 = 53.16, p = 0.000). Specifically, the plasma TAC levels were markedly reduced after the treatment with PEO and SEO at the 1:9 dilution, compared to the control group, and with PEO and FEO at 1:99 (Fig. 7A). A similar decrease was observed at a dilution of 1:99 following the administration of PEO and FEO (Fig. 6A). The TAC levels, which reflect the overall antioxidant capacity of the erythrocyte system, also showed significant variation (F11, 72 = 8.11, P = 0.000), particularly at the 1:99 dilution of the three EOs tested (Fig. 7B). Notably, the erythrocyte TAC values increased significantly following the treatment with PEO, SEO, and FEO, indicating an increase in systemic antioxidant defence mechanisms under the EO exposure.

Fig. 7: Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) level in human blood plasma (A) and erythrocytes (B) measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of essential oils from pine (PEO), spruce (SEO), and fir (FEO) in an in vitro study.* Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:9, compared to the control;** Differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in samples treated with EOs at a dilution of 1:99, compared to the control.

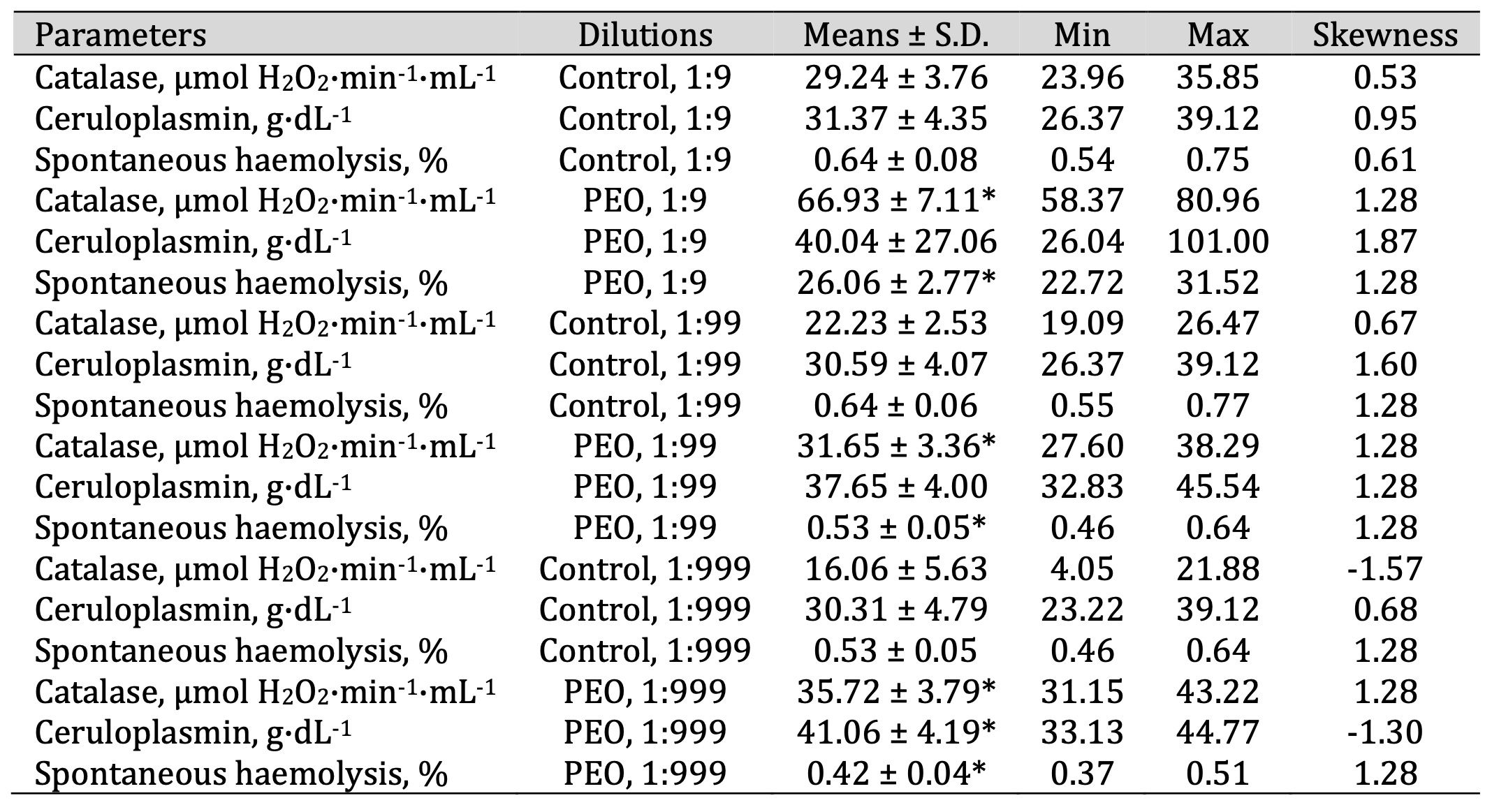

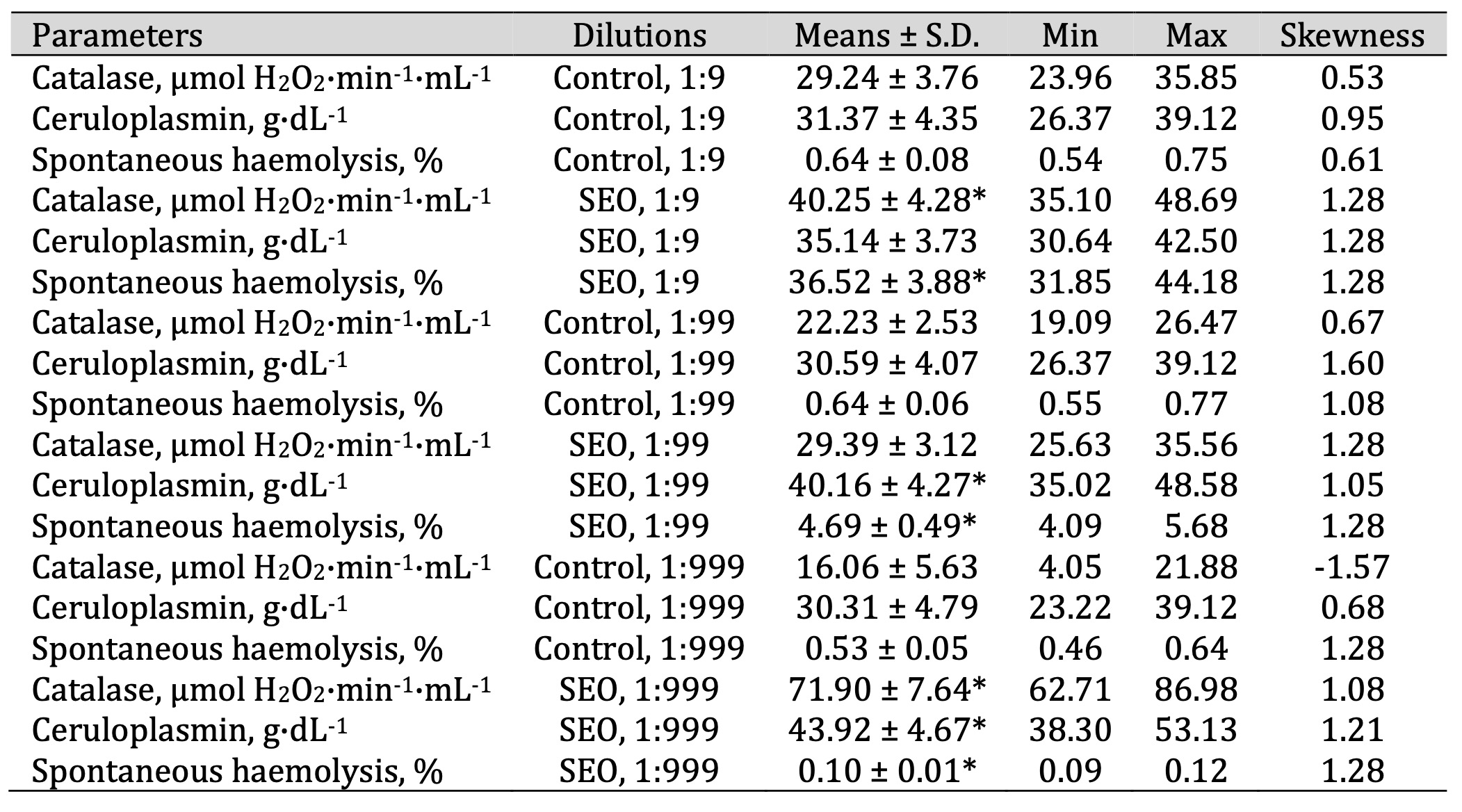

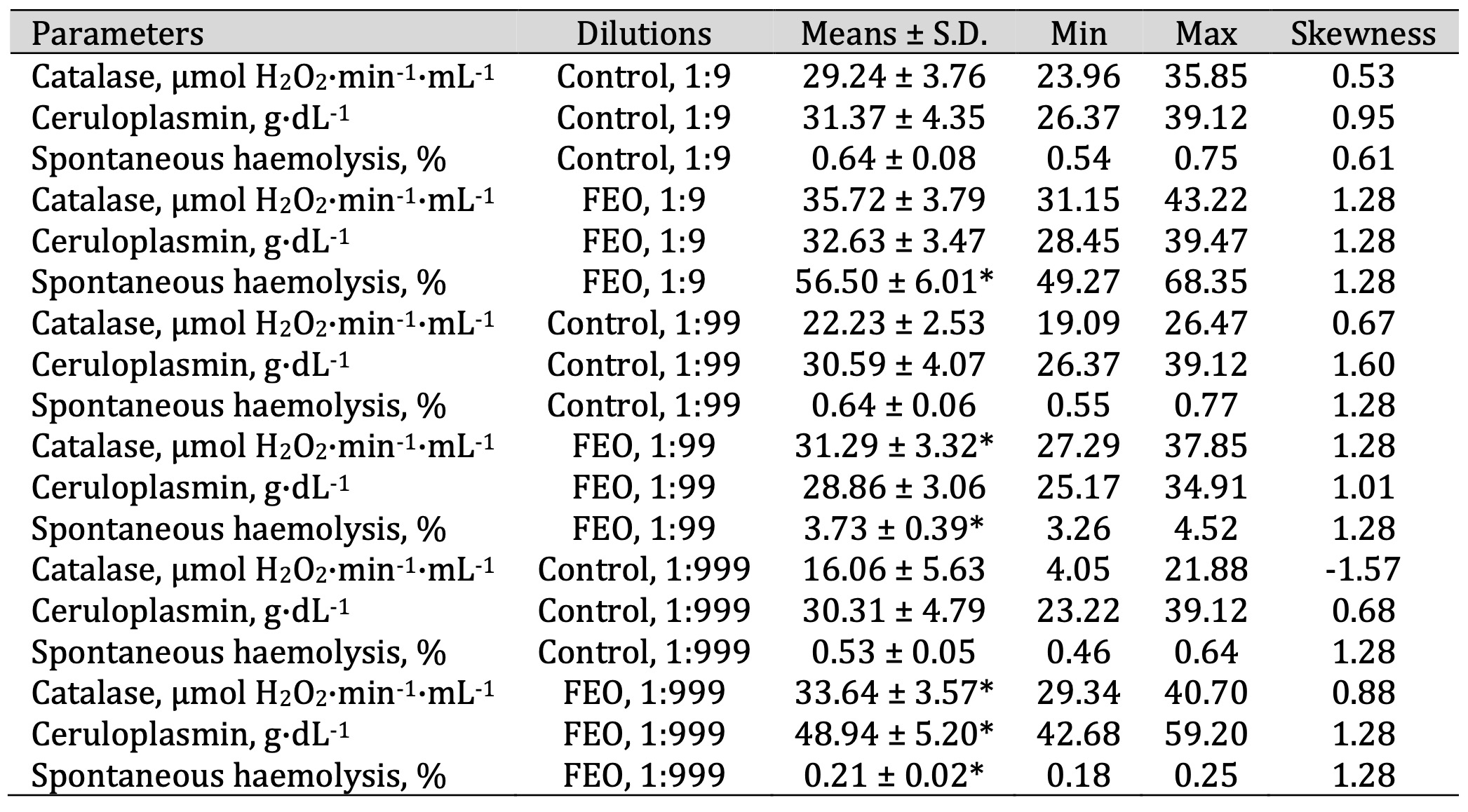

The current study evaluated the activity of catalase, one of the main enzymes in the second-line

antioxidant defence system, alongside ceruloplasmin levels. Ceruloplasmin, a copper-containing

acute-phase

enzyme, plays an essential role in copper metabolism and increases during inflammatory processes. In

addition, spontaneous haemolysis of human erythrocytes was evaluated in vitro following the

EO

exposure. All analyses were performed in a dose-dependent manner across three independent dilutions,

with

results summarised in Tables 6-8.

This study assessed the activity of catalase, a key enzyme of the secondary antioxidant defence

system,

together with ceruloplasmin levels. The data obtained revealed significant variations in catalase

activity

following the EO exposure (F11, 72 = 89.56, P = 0.000). Specifically, a statistically

significant increase in catalase activity was observed in the three EO dilutions, compared with the

control sample data. This suggests strong stimulation of the enzymatic antioxidant defence system by

PEO.

Similar upward trends were also observed for SEO and FEO (Tables 6, 7, and 8).

Table 6: Catalase activity (μmol H2O2·min-1·mL-1), ceruloplasmin level (g·dL-1), and spontaneous haemolysis level (%) in human blood measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of pine essential oil (PEO) in an in vitro study. * P < 0.05 for each of the three essential oil dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999), compared to the control samples, determined by Student’s t-test

Table 7: Catalase activity (μmol H2O2·min-1·mL-1), ceruloplasmin level (g·dL-1), and spontaneous haemolysis level (%) in human blood measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of spruce essential oil (SEO) in an in vitro study. * P < 0.05 for each of the three essential oil dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999), compared to the control samples, determined by Student’s t-test

Table 8: Catalase activity (μmol H2O2·min-1·mL-1), ceruloplasmin level (g·dL-1), and spontaneous haemolysis level (%) in human blood measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of fir essential oil (FEO) in an in vitro study. * P < 0.05 for each of the three essential oil dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999), compared to the control samples, determined by Student’s t-test

The ceruloplasmin levels (F11, 72 = 12.56, P = 0.000) increased significantly

following

the

SEO

administration at a dilution of 1:99 and 1:999, compared with the untreated control group.

Similarly,

both

FEO administration variants led to a statistically significant elevation of ceruloplasmin

values

in

a

concentration-dependent manner. This finding is particularly important, as ceruloplasmin not

only

reflects

copper metabolism but also acts as an acute-phase protein and an important antioxidant,

providing

additional insight into the systemic response to essential oils.

Additionally, multidirectional effects on spontaneous haemolysis were observed following the

EO

exposure

(F11, 72 = 492.09, P = 0.000). PEO induced the highest haemolysis at the 1:9

dilution

while

significantly reducing it at 1:99 and 1:999 (F11, 72 = 492.09, p < 0.001; Table

6).

Conversely, SEO caused a significant increase in spontaneous haemolysis at 1:9 and 1:99 but

contributed

to

a reduction at 1:999 (Table 7). In contrast, FEO showed a clear dose-dependent pattern, with

erythrocyte

haemolysis decreasing progressively as the concentration declined, suggesting a potential

membrane-stabilising effect at lower doses (Table 8).

Taken together, these analyses highlight the importance of both the type and concentration of

essential

oil in modulating oxidative stress markers, particularly ceruloplasmin levels and spontaneous

haemolysis

in erythrocytes. Therefore, the results indicate that essential oils can significantly

influence

oxidative

cellular processes, suggesting potential therapeutic applications in the management of

inflammatory

and

oxidative stress-related conditions. In summary, the analysis of the VOCs in the

conifer-derived

EOs

revealed that the predominant constituents identified by GC-MS were monoterpenes, primarily

α-pinene,

β-pinene, and borneol, consistent with previous studies.

Further confirmation of the presence of the two main compounds in conifer-derived EOs,

α-pinene

and

β-pinene, was provided by the FTIR analysis, with these two compounds significantly

contributing

to

the

absorption spectrum. In contrast, SEO was characterised by the presence of α-pinene and

(–)-bornyl

acetate, while FEO was distinguished by the presence of methyl acetate and (+)-borneol. This

compositional

diversity demonstrates that despite the dominance of monoterpenes, each oil type has a unique

chemical

fingerprint that may directly relate to distinct biological responses.

The biochemical assays demonstrated that these EOs exerted dose-dependent effects on the human

plasma

and

erythrocytes, notably influencing lipid peroxidation, oxidative modification of proteins, and

total

antioxidant capacity (TAC). They stimulated lipid peroxidation and protein derivative

modification

(both

aldehyde and ketone types) while reducing plasma TAC. These effects are consistent with the

biphasic

nature of EOs, which act as antioxidants at lower concentrations but display pro-oxidative

activity

at

higher doses.

Additionally, the EO exposure also significantly increased catalase activity and ceruloplasmin

levels.

This indicates a systemic oxidative stress response. The EOs also induced haemolysis in

erythrocytes,

providing further evidence of their pro-oxidative effects at higher concentrations. The EO

exposure

also

significantly increased catalase activity and ceruloplasmin levels, indicating a systemic

oxidative

stress

response. Furthermore, enhanced erythrocyte haemolysis was observed, supporting the

pro-oxidant

potential

of EOs at higher concentrations.

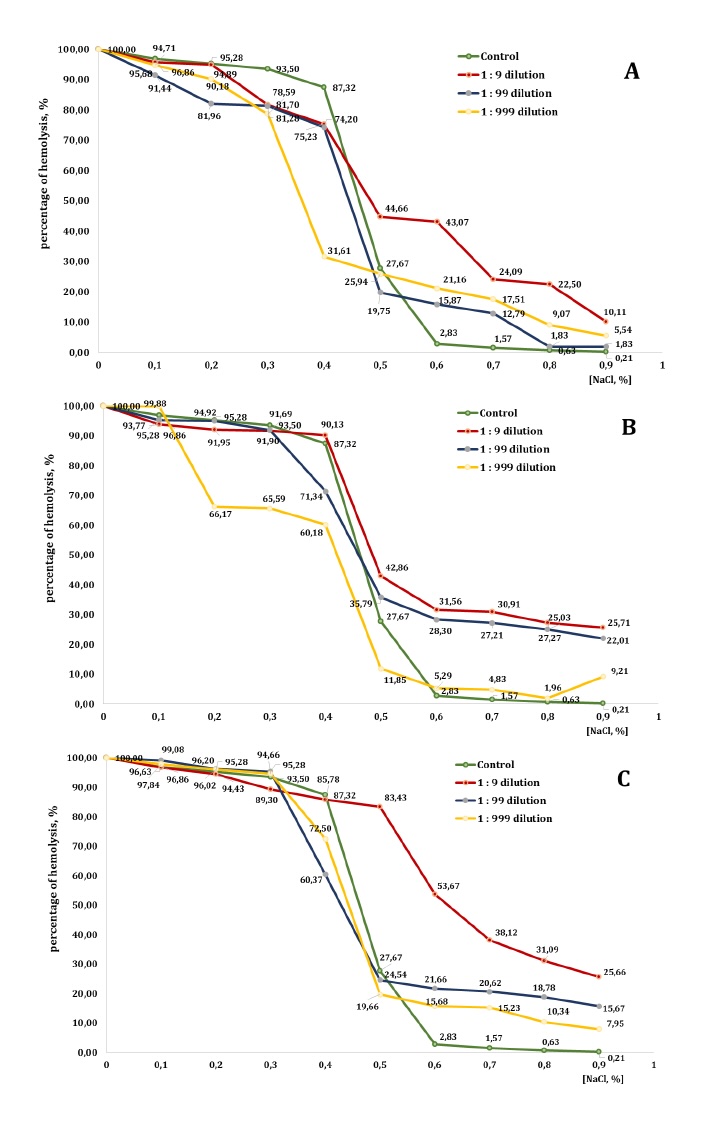

NaCl-induced haemolysis. The effects of PEO on erythrocyte haemolysis were assessed at different dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) across a range of NaCl concentrations (0.9-0%). As expected, the control group (without PEO) exhibited a pattern of osmotic haemolysis characterised by minimal haemolysis at physiological NaCl concentrations (0.9-0.6%), followed by a sharp increase at 0.5-0.3% NaCl and complete haemolysis at 0% NaCl.

Fig. 8: Level of erythrocyte haemolysis (B) measured after treatment with three dilutions (1:9, 1:99, and 1:999) of essential oils from pine (PEO), spruce (SEO), and fir (FEO) in an in vitro study.

In the presence of PEO, however, the haemolysis profile was altered in a concentration- and

dilution-dependent manner. In isotonic and mildly hypotonic conditions (0.9-0.6% NaCl), the

1:9

dilution

markedly increased haemolysis, compared with the control group (e.g., 10.11% vs. 0.21% at 0.9%

NaCl

and

43.07% vs. 2.83% at 0.6% NaCl), indicating enhanced membrane destabilisation. The 1:99 and

1:999

dilutions

also promoted haemolysis at these NaCl concentrations, although to a lesser extent than the

1:9

dilution.

At 0.5% NaCl, haemolysis in the control group reached 27.67%, whereas all PEO dilutions

induced

higher

levels of lysis: 44.66% for 1:9, 19.75% for 1:99, and 25.94% for 1:999, thereby confirming the

pro-haemolytic effect of PEO under moderate osmotic stress. At 0.4% NaCl, haemolysis was

already

elevated

in the control group (87.32%), and PEO produced variable effects. The 1:9 and 1:99 dilutions

slightly

reduced haemolysis to 75.23% and 74.20%, respectively, whereas the 1:999 dilution still

promoted

lysis,

reaching 31.61%. These results demonstrate a concentration-dependent dual action of PEO. In

strongly

hypotonic conditions (0.3-0.1% NaCl), both the control and the PEO-treated groups approached

maximum

haemolysis (>80-96%), with only minor differences between the treatments. At complete

osmotic

lysis

(0%

NaCl), all groups reached 100% haemolysis. In summary, PEO displayed a biphasic effect on

erythrocyte

membrane stability. In isotonic and moderately hypotonic conditions, particularly at higher

concentrations, PEO significantly enhanced haemolysis, indicating increased membrane

fragility.

By

contrast, in strongly hypotonic conditions, its impact diminished and, in some cases, partial

protective

activity against lysis was evident.

The presence of SEO significantly affected erythrocyte stability, particularly at higher

concentrations.

In isotonic conditions (0.9% NaCl), haemolysis remained low in the control group (0.21%) but

increased

markedly across all SEO dilutions: 25.71% (1:9), 22.01% (1:99), and 9.21% (1:999). A similar

trend

was

observed in mildly hypotonic conditions (0.8-0.6% NaCl), where haemolysis increased in all

dilutions,

compared to the control. For example, at 0.7% NaCl, the control sample exhibited 1.57%

haemolysis,

whereas

the 1:9, 1:99, and 1:999 dilutions produced 30.91%, 27.21%, and 4.83% haemolysis,

respectively.

At

0.5%

NaCl, SEO further amplified haemolysis (42.86%, 35.79%, and 11.85%, compared with 27.67% in

the

control),

confirming its destabilising action under moderate osmotic stress. At 0.4% NaCl, haemolysis in

the

control

reached 87.32%. The 1:9 dilution caused an even greater lysis (90.13%), while the 1:99 and

1:999

dilutions

reduced it slightly (to 71.34% and 60.18%, respectively), suggesting a partial

concentration-dependent

protective effect. In stronger hypotonic conditions (0.3-0.1% NaCl), both the control and the

SEO-treated

groups exhibited extensive haemolysis (>90%). Nevertheless, some differences were noted:

the

1:9

dilution showed slightly reduced values, compared to the control group (e.g. 91.69% vs. 93.50%

at

0.3%

NaCl), while the 1:999 dilution displayed inconsistent results, providing partial protection

at

0.3-0.2%

NaCl but producing higher haemolysis at 0.1% NaCl (99.88%). Complete lysis (100%) occurred in

all

groups

at 0% NaCl.

In summary, SEO markedly enhanced haemolysis in isotonic and moderately hypotonic conditions,

particularly

at higher concentrations, indicating pronounced membrane-destabilising activity. Under more

severe

osmotic

stress, however, SEO exhibited mixed effects: partial protective properties were observed at

intermediate

dilutions, but there was no significant impact in the conditions of complete lysis.

By contrast, the addition of FEO markedly altered the haemolysis patterns, particularly at

higher

concentrations. At the NaCl concentration of 0.9%, haemolysis in the control group was minimal

(0.21%)

but

increased substantially in the presence of FEO: 25.66% (1:9), 15.67% (1:99), and 7.95%

(1:999).

A

similar

trend was observed at 0.8-0.6% NaCl, where all dilutions promoted significantly greater

haemolysis,

compared with the control. For example, at 0.6% NaCl, haemolysis reached 53.67%, 21.66%, and

15.68%

in

the

FEO groups, versus only 2.83% in the control.

At 0.5% NaCl, the control group exhibited 27.67% haemolysis; however, the 1:9 dilution of FEO

produced

a

dramatic increase of 83.43%, The 1:99 and 1:999 dilutions caused more moderate increases,

reaching

24.54%

and 19.66%, respectively. At 0.4% NaCl, haemolysis in the control group was 87.32%. The 1:9

dilution

produced a comparable value (85.78%), while the 1:99 and 1:999 dilutions reduced haemolysis

slightly

to

60.37% and 72.5%, respectively, suggesting concentration-dependent modulation of erythrocyte

lysis.

In

more hypotonic conditions (0.3-0.1% NaCl), haemolysis exceeded 89% in all groups. The 1:99

dilution

consistently yielded higher values (95.28-99.08%), while the 1:999 dilution produced results

similar

to

the control. Complete haemolysis (100%) was observed at 0% NaCl in all conditions. In summary,

FEO

exerted

a strong pro-haemolytic effect at isotonic and moderately hypotonic NaCl concentrations,

particularly

at

the highest concentration (1:9 dilution), which induced markedly greater membrane fragility.

In

more

extreme hypotonic conditions, however, its influence was less pronounced and, at certain

dilutions,

even

exhibited partial protective effects.

Discussion

This study provides new insights into the effects of conifer-derived EOs on oxidative stress markers, antioxidant responses, and erythrocyte stability in human blood in vitro. By integrating chemical characterisation with biochemical assays, clear relationships were established between the VOC profiles of these essential oils and their diverse biological effects. This comprehensive approach underscores the bioactive potential of conifer-derived EOs, highlighting their dual antioxidant and pro-oxidant activities in a concentration- and composition-dependent manner. Notably, these in vitro findings offer a valuable basis for assessing the therapeutic potential and safety profiles of EOs prior to their potential application in preclinical and clinical studies.

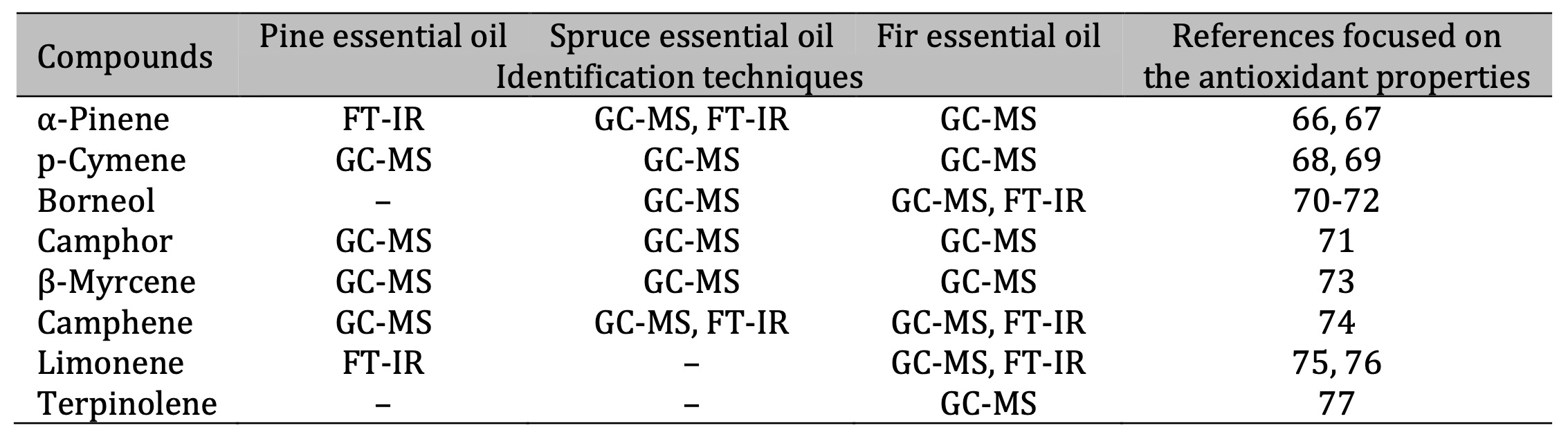

Comprehensive chemical analyses using GC-MS, PTR-MS, and FTIR confirmed the terpene-rich composition of the three EOs, in line with previous reports on coniferous species [7, 60-62]. The major constituents identified were α-pinene, β-pinene, borneol, camphene, and limonene although each oil type exhibited a distinct profile. SEO was characterised by elevated levels of (–)-bornyl acetate, FEO contained (+)-borneol and methyl acetate, while PEO was particularly rich in α-pinene and β-pinene. These compositional differences likely explain the variability observed in oxidative and haemolytic responses. Notably, several of these compounds, including α-pinene, p-cymene, and borneol, are well known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [63-65] (Table 9). Thus, the chemical heterogeneity of the oils provides a mechanistic basis for understanding their biological diversity. The overlap between our findings and those of previous chemical and functional studies highlights the consistency of bioactive terpenes in conifer-derived EOs from a chemotaxonomic perspective.

Table 9: Identification of antioxidant compounds in essential oils. The identification techniques used are specified below: GC-MS (gas chromatography–mass spectrometry) and FT-IR (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy). Note: It should be noted that PTR-MS (proton transfer reaction–mass spectrometry) was also applied; this technique allows the mass of compounds to be defined, but not their structure. Therefore, this technique is not included in the table because the determined masses do not unambiguously define the compounds. The results of the PTR-MS analysis are discussed in the corresponding chapter

The results of the present study clearly indicate that the three conifer-derived EOs tested significantly impact the oxidative–antioxidative balance in human blood in vitro, albeit in a complex manner. Marked stimulation of lipid peroxidation and oxidative protein modification was detected, confirming the pro-oxidative potential of the oils, which were most pronounced for FEO. At the same time, compensatory responses to oxidative stress were triggered, including enhanced catalase activity and elevated ceruloplasmin levels, suggesting an adaptive role under increased oxidative stress. These dual effects emphasise the hormetic nature of EO activity: low doses may trigger beneficial adaptive responses, whereas high doses can cause damage [78]. These findings underscore the biphasic nature of EO activity, which may exert either pro- or antioxidant effects, depending on the concentration.

The observed changes in erythrocyte haemolysis further confirm that the tested EOs influence cell membrane integrity in a concentration- and type-dependent manner. In isotonic and moderately hypotonic conditions, enhanced haemolysis was evident, indicating EO-induced enhancement of membrane fragility. Conversely, in strongly hypotonic NaCl conditions, partial protective effects were observed. These results imply that the biological activity of EOs is not unidirectional but rather modulated by both environmental conditions and the concentration, which may hold significance for their therapeutic application. The present data highlight the dual nature of the essential oils under investigation – their ability to induce oxidative stress while simultaneously activating cellular defence systems. This duality is consistent with earlier reports indicating that α-pinene, borneol, and related monoterpenes can exert protective effects, depending on the dose and the cellular context [67, 72, 79]. Therefore, precise dosage control and a thorough understanding of the biological context in which they act are required for the therapeutic use of these EOs.

The present study demonstrated that all the conifer-derived EOs tested exerted concentration-dependent effects on oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, enzymatic activity, and erythrocyte stability, with clear differences between plasma and erythrocyte responses. For PEO, lipid peroxidation markers increased markedly across the dilutions in both plasma and erythrocytes, accompanied by moderate-to-high variability (coefficient of variation (CV% = 8.5-22%) and substantial effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.8-1.8). Protein oxidation increased moderately in the erythrocytes, while changes in the plasma were less pronounced. Plasma TAC showed a pronounced decrease, particularly at a dilution of 1:9 (CV% <10%, d >1.0), whereas erythrocyte TAC was less affected. Catalase activity fluctuated without a clear dose–response pattern (CV% = 15–20%, d <0.3). The most striking finding emerged from the haemolysis assay, where PEO induced a strong dose-dependent disruption of erythrocyte membranes, exceeding 50% at high concentrations, with low variability (CV% <12%) and very large effect sizes (d >2.0). These results confirm the potent membrane-damaging potential of PEO. The high potency of PEO suggests that it could be of particular biomedical interest. However, it also raises concerns about its cytotoxicity at elevated concentrations.

By comparison, SEO also induced a significant redox imbalance, albeit with slightly lower intensity. Plasma TBARS increased markedly at a dilution of 1:9 (CV% = 10-14%, d = 1.0-1.5), while the highest increase in erythrocyte TBARS was observed at a dilution of 1:99, with greater variability (CV% = 17-21%) but still large effect sizes (d > 0.9). Protein oxidation was more evident in the erythrocytes than in the plasma. Meanwhile, TAC decreased consistently in the plasma (CV% <10%, d = 1.1-1.6), confirming strong suppression of the antioxidant potential. Catalase activity varied moderately (CV% = 14-18%, d <0.4), suggesting limited enzymatic contribution. Haemolysis increased in a dose-dependent manner, reaching 30-40% at higher concentrations (CV% = 9-13%, d >1.8), indicating biologically relevant, yet less severe, membrane destabilisation than with PEO. Thus, although SEO demonstrated significant oxidative effects, its overall cytotoxicity appears to be relatively mild.

FEO exhibited moderate effects, with plasma TBARS levels significantly increasing at a 1:9 dilution (CV% = 9-13%, d = 1.0-1.4), while erythrocyte TBARS levels peaked at intermediate concentrations (CV% = 16-20%, d = 0.7-1.0). Protein oxidation was minimal (CV% = 5-9%, d = 0.2-0.4) and plasma TAC notably decreased at higher concentrations (CV% <10%, d >1.0), whereas erythrocyte TAC remained relatively stable. Catalase activity fluctuated inconsistently (CV% = 15-19%, d <0.3). Haemolysis increased gradually, reaching 20–30% at the highest concentrations (CV% = 8-11%, d >1.5), indicating weaker, yet reproducible, erythrocyte destabilisation, compared to PEO and SEO. Overall, these results suggest that FEO may be the safest of the tested oils in terms of redox balance and cytotoxicity.

These results highlight a clear hierarchy of pro-oxidant and cytotoxic potential, with PEO exerting the strongest impact on redox balance and erythrocyte integrity, followed by SEO and, finally, FEO. While the three EOs exhibited some antioxidant properties, their higher concentrations disrupted oxidative homeostasis and promoted haemolysis, underscoring the delicate balance between beneficial and pro-oxidant effects in biological systems. This ranking of activities is consistent with previous comparative studies of Pinaceae EOs, which further supports the reliability of the present findings [3].

Further evidence for this dualistic activity was provided by the assessment of enzymatic defences. The exposure to the three EOs, particularly PEO, significantly enhanced catalase activity in the plasma, suggesting an adaptive response to elevated oxidative stress. Likewise, the elevated ceruloplasmin levels following the EO treatment indicate the activation of systemic antioxidant pathways [80]. This finding is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that ceruloplasmin plays a pivotal role in maintaining redox balance and iron metabolism, particularly in pathological conditions in which oxidative stress is a primary driver [81, 82]. It should be emphasised that such enzymatic responses are a fundamental protective mechanism of the organism, designed to counteract cellular damage caused by ROS [83]. Such compensatory mechanisms may explain the paradoxical coexistence of antioxidant and pro-oxidant markers observed in our data.

Moving on to the cellular effects of systemic enzymatic defences, the erythrocyte haemolysis assays provided valuable insights into the interaction of EOs with biological membranes. Increased haemolysis at isotonic and moderately hypotonic NaCl concentrations suggests that high concentrations of EOs destabilise membranes, potentially via oxidative modification of proteins and lipids [84]. Interestingly, under extreme hypotonic stress, protective effects were occasionally observed, reflecting a biphasic environment-dependent action. The dose-dependent shifts in haemolytic behaviour, particularly evident with SEO and FEO, demonstrate that subtle compositional differences among conifer-derived EOs can yield distinct biological effects. This biphasic nature highlights the importance of combining biochemical data and functional assays to gain a comprehensive understanding of EO bioactivity [85].

Several studies have highlighted the chemical diversity and bioactive potential of EOs derived from species of the Pinaceae family. Xie et al. (2015) reported that the EOs of six Chinese Pinus taxa were primarily composed of α-pinene, β-caryophyllene, and bornyl acetate, and exhibited significant antioxidant activity in DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS assays [86]. Similarly, Bonikowski et al. (2015) demonstrated that oils of Polish Pinus uncinata and P. uliginosa needles were rich in monoterpenes, with bornyl acetate and α-pinene being the main constituents [87]. They also noted considerable variation in secondary metabolites, such as limonene, myrcene, germacrene D, and δ-cadinene. More recently, Dakhlaoui et al. (2023) confirmed that oils from Pinus halepensis in Tunisia display strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities, alongside cytotoxic effects against MCF-7 cells [88]. These examples clearly demonstrate that phytochemical profiles are influenced by genetic and taxonomic factors as well as geographic origin, climate, soil type, and seasonal variations [7]. These findings underscore the impact of geographic and environmental factors on the oil composition and biological properties.

In addition to Pinus spp., the EOs from Picea abies and Abies alba also demonstrated considerable bioactivity. Sandulovici et al. (2024) reported that vegetative buds from Romanian spruce had high concentrations of phenolic compounds and EO constituents, including D-limonene, α-cadinol, and δ-cadinene [89]. These compounds impart significant antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Garzoli et al. (2021) compared the liquid and vapour phases of Picea abies and Abies alba oils, revealing that the vapour phase exhibited stronger antibacterial activity [3]. Meanwhile, Pinus mugo oils demonstrated the highest antioxidant capacity, with α-pinene identified as a key bioactive compound. Furthermore, Postu et al. (2019) demonstrated that Pinus halepensis oil reduced amyloid beta-induced oxidative stress and memory impairment in a rat model, suggesting potential neuroprotective properties [90]. This neuroprotective potential is of particular interest, given the increasing demand for natural compounds that can counteract neurodegenerative processes [91]. Taken together, these findings highlight the rich chemical diversity of Pinaceae EOs and their multifaceted bioactivities, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties.

The broader biomedical relevance of these findings is supported by converging evidence from other studies. For instance, pine-derived oils have been demonstrated to inhibit bacterial virulence [92], suppress the production of inflammatory cytokines [93], and accelerate wound healing [14, 16]. Similarly, spruce and fir oils exhibit antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral properties [17, 94]. The presence of overlapping bioactive terpenes, such as α-pinene, borneol, and bornyl acetate, across these studies reinforces their conserved functional roles. At the same time, the variation in the EO composition due to environmental, seasonal, and methodological factors underscores the necessity for standardisation and comprehensive chemical characterisation in future applications. Without harmonisation, the reproducibility of research related to EO could be limited [7, 95].

Although the antioxidant properties of plant polyphenols are well documented, EOs represent a comparatively less extensively explored yet highly relevant class of natural products with redox-modulating potential [96]. Importantly, the effects of EOs on oxidative processes are often dualistic and strongly concentration dependent. At low doses, they can scavenge ROS, enhance enzymatic antioxidant defences, and stabilise membranes. By contrast, at higher concentrations, they may disrupt membrane integrity, induce lipid peroxidation, and exacerbate oxidative stress [83, 97]. This dualism reflects a hormetic mechanism, whereby low doses have a protective effect, whereas high doses are harmful. This phenomenon is becoming increasingly recognised in toxicology and pharmacology [98]. This bidirectional activity underscores the complexity of EO bioeffects and highlights the necessity of carefully designed experimental approaches to fully characterise their pharmacological potential.

Chemical analysis confirmed that the dominant terpenes in the oils that were tested were α-pinene, β-pinene, borneol, camphene and limonene. These lipophilic monoterpenes can readily partition into erythrocyte membranes, where they alter lipid packing and bilayer fluidity, thereby affecting redox homeostasis [99, 100]. For example, α-pinene and limonene are known to modulate membrane permeability and stimulate reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation through mitochondrial and NADPH oxidase-related pathways [101, 102]. In contrast, oxygenated terpenes such as borneol and bornyl acetate can stabilise lipid bilayers and scavenge free radicals, thereby contributing to the observed adaptive antioxidant responses [103]. These differential interactions at the lipid–water interface provide a mechanistic explanation for the biphasic redox effects observed in this study: low concentrations enhance antioxidant defences, whereas higher concentrations induce oxidative damage.

Enhanced lipid peroxidation and oxidative protein modification, particularly in PEO-treated samples, suggests that certain terpenes can promote membrane oxidation and fragility. This may be due to direct radical formation at the lipid surface or indirect oxidative signalling through ROS-mediated cascades [104]. The concurrent activation of catalase and increased ceruloplasmin levels suggest that erythrocytes and plasma proteins are attempting to counterbalance this oxidative challenge. These compensatory effects illustrate a hormetic pattern, whereby mild oxidative stress triggers endogenous defences while excessive exposure results in cellular damage [78].

Haemolysis assays also supported this dualistic activity. Enhanced lysis in isotonic and mildly hypotonic conditions indicates membrane destabilisation via oxidative lipid perturbation. In contrast, partial protection under strongly hypotonic stress may reflect a membrane-stiffening effect induced by specific oxygenated terpenes [105]. Therefore, the biological outcome depends not only on the concentration of the essential oil, but also on the physicochemical environment and the composition of the terpenes. Previous studies have reported similar biphasic phenomena for monoterpenes of the Pinaceae family, confirming that subtle structural differences can significantly impact redox and cytotoxic behaviour [87, 88].

Recent reviews and experimental studies confirm that EOs may exert either antioxidant or pro-oxidant effects, depending on their composition, concentration, and the cellular model used, thereby highlighting their inherently dualistic nature [106]. Modulation of the redox balance represents a promising strategy for overcoming therapy resistance in cancer treatment. For instance, several essential oils, including those derived from Pinaceae, have been shown to trigger ROS-dependent apoptosis and may potentially enhance tumour sensitivity to conventional therapies [107-110]. This aligns with the broader trend of exploring phytochemicals as adjuvants in oncology. This approach recognises that natural compounds can enhance the efficacy of standard treatments while reducing side effects [111]. Although the research on the use of EOs as anticancer agents is relatively recent, it is noteworthy that nearly half of conventional chemotherapeutic agents are of plant origin, with approximately 25% being directly derived from plants and another 25% representing chemically modified versions of plant products [112]. These complex and interdependent mechanisms have prompted researchers to explore these effects in a physiologically relevant context, with in vitro models based on human blood gaining increasing importance.

This study was conducted exclusively in vitro using human blood, without cytotoxicity or cell viability assays. Variability between donors may have influenced some biochemical parameters, so these results should be interpreted with caution. Further ex vivo or in vivo models are required to validate the suggested redox-modulatory mechanisms. While the data highlight the redox-modulating and membrane-active potential of conifer EOs, any clinical extrapolation remains premature. The dual antioxidant–pro-oxidant nature of these compounds means that their therapeutic application will require precise dose control and rigorous toxicological evaluation, so establishing safe and effective therapeutic windows should be prioritised before considering human use.

Thus, these findings emphasise the complex and multifaceted biological activity of Pinaceae EOs. While they exhibit promising antioxidant and cytoprotective properties, their capacity to induce oxidative protein modifications and haemolysis at higher concentrations highlights the importance of appropriate dosing. The balance between beneficial and harmful effects is determined by their chemical composition and concentration [113]. Therefore, establishing safe and effective therapeutic windows through dose-response studies and clinical trials is a critical step before considering clinical application [114]. This underscores the need for carefully defined dosing strategies and further mechanistic studies to determine the thresholds at which the antioxidant benefits outweigh the pro-oxidant risks. Such efforts will be critical to ensuring the safe and effective use of Pinaceae EOs in biomedical contexts.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that conifer-derived EOs exhibit complex concentration-dependent biological activities in human plasma and erythrocytes in vitro. While the three oils were dominated by similar terpenes, i.e. α-pinene, β-pinene, borneol, and bornyl acetate, their distinct chemical profiles produced different biological outcomes. Based on the multi-component decomposition of infrared (FTIR) spectra, it was found that α-pinene and β-pinene constituted approximately 55% of PEO, α-pinene, (-)-bornyl acetate, and camphene were predominant in SEO, and FEO contained methyl acetate and (+)-borneol. Additionally, the infrared spectroscopic measurements clearly indicate that the PEO sample is characterised by the lowest content of compounds with hydroxyl and carbonyl groups among the three samples.